The COVID-19 pandemic has had a severe impact on mortality in the United States, leading to life expectancy decreasing in the U.S. by far more than in other large, wealthy countries. The pandemic has also exacerbated access barriers and spotlighted the health inequities experienced by people of color. Health spending in the U.S. continues to far exceed what peer countries spend and out-of-pocket costs grew rapidly last year.

In this brief, we assess the current state of the U.S. health system using dozens of data points on costs, outcomes, and quality of and access to care from the Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker and the accompanying Health System Dashboard. We also discuss the outlook for 2023 in the context of the likely end of the public health emergency, depletion of federal COVID funds, and strain on the healthcare workforce.

Health Outcomes

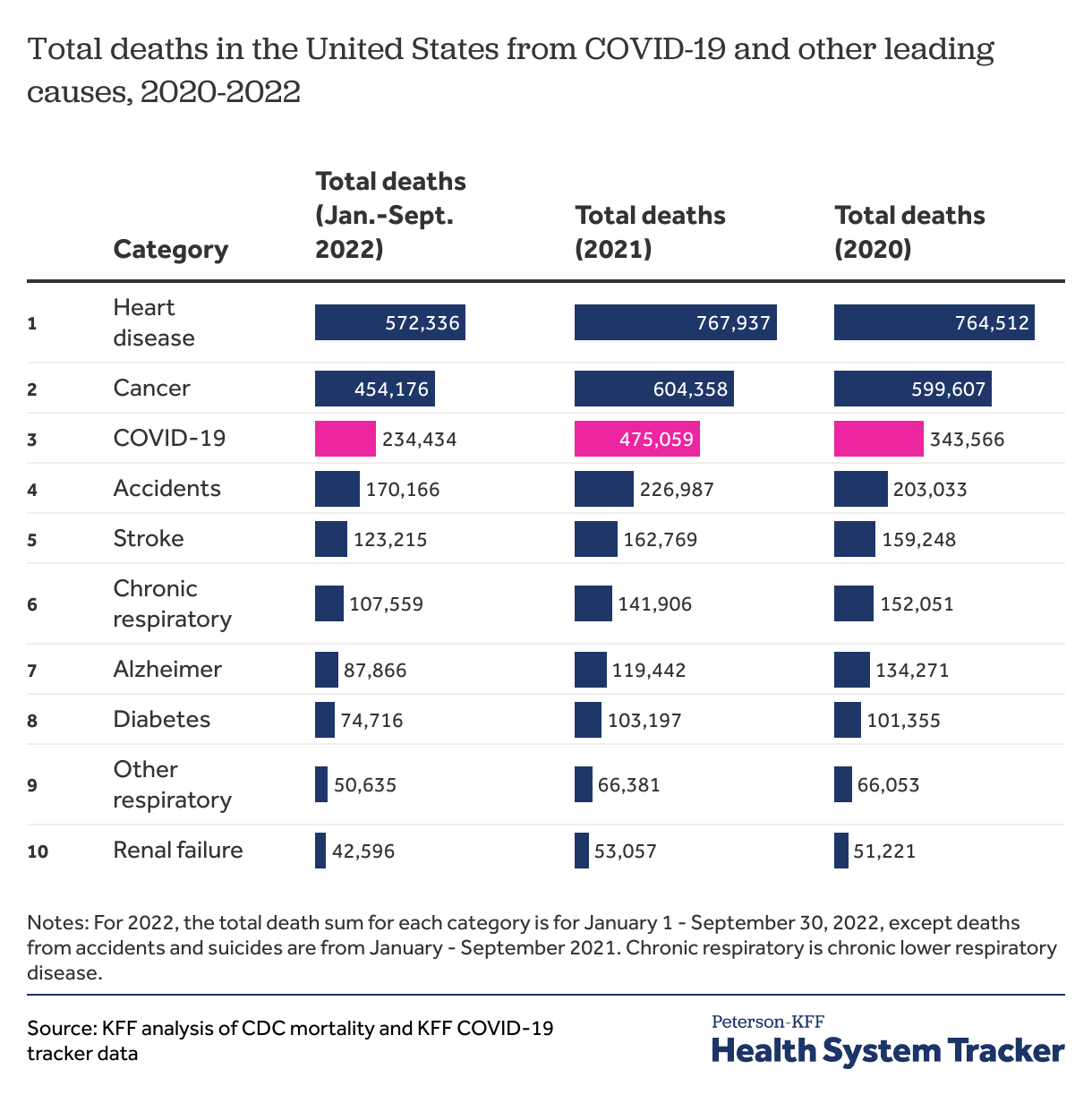

Since the start of the pandemic, life expectancy has dropped across all race and ethnicity groups in the U.S. However, people of color experienced a greater decline in life expectancy. Since 2019, life expectancy for Black and Hispanic people has declined by 4 or more years, while life expectancy for White people has declined by 2.4 years. COVID-19 continues to contribute to excess mortality in 2022, and is on track to be the third leading cause of death in the U.S. for the third consecutive year.

COVID-19 is on track to be the third leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2022

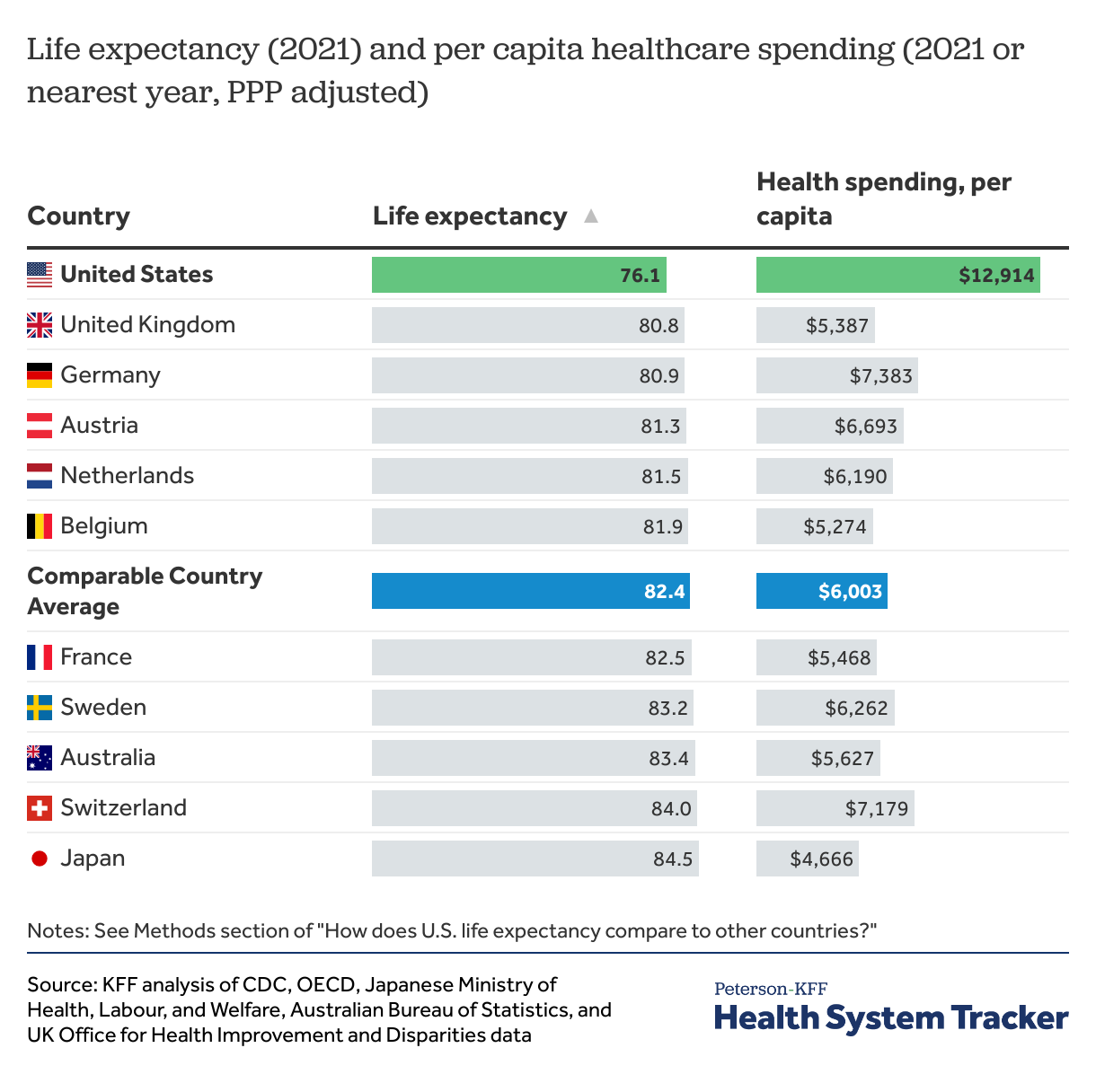

By contrast, in most similarly large and wealthy nations, life expectancy began to rebound in 2021, widening a pre-existing gap between the U.S. and its peers. The U.S. has the lowest life expectancy compared to similarly large, wealthy peer countries, despite spending the most money per capita on healthcare. Life expectancy at birth in the U.S. was 76.1 years, compared to 82.4 years in other comparable countries, on average in 2021.

People in the U.S. live shorter lives and spend much more on healthcare than people in peer countries

Health Spending

Overall health spending continued to grow in 2021, reaching a total of nearly $4.3 trillion dollars. This amounts to 18.3% of the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) and average of $12,914 per capita.

The U.S. continues to have the highest health spending per capita among comparable countries. In 2021, the U.S.’s $12,914 per capita health spending was more than double the average for other comparably large and wealthy countries ($6,003). The country spending the second highest amount on health per capita was Germany, at $7,383.

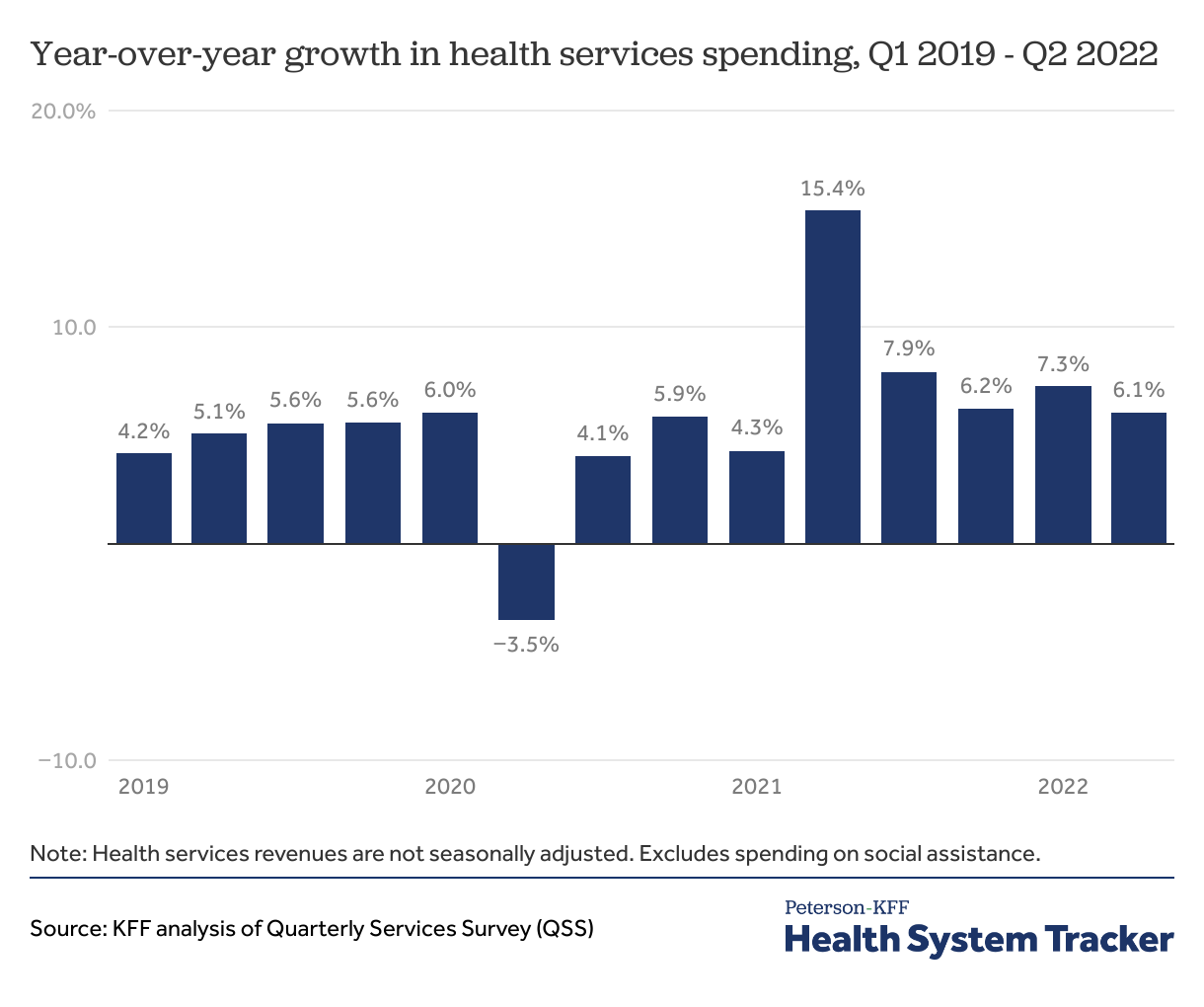

As of second quarter 2022, health spending in the U.S. has rebounded since the beginning of the pandemic and spending on health services is growing at pre-pandemic levels.

In 2022, spending on health services has grown at pre-pandemic rates

In 2022, price growth in the health sector has been slower than general economic inflation. However, the cumulative increase in health prices in the past two decades continue to surpass overall prices. It is unclear whether growth in prices of goods and labor costs in 2022 will eventually flow through to the health sector. It is possible the federal government’s price-setting for Medicare may somewhat moderate inflation in the health sector.

Healthcare Access and Utilization

The coronavirus pandemic compounded pre-existing barriers to accessing care in the U.S. In 2021, 21% of adults in the U.S. either delayed or did not get care due to pandemic-related barriers.

Health services use dropped early in the pandemic as steps were taken to avoid in-person spread of COVID-19. Virtual care delivered via telehealth somewhat filled the need for accessing care. However, as of October 2022, inpatient care still had not rebounded to pre-pandemic levels.

Healthcare Affordability

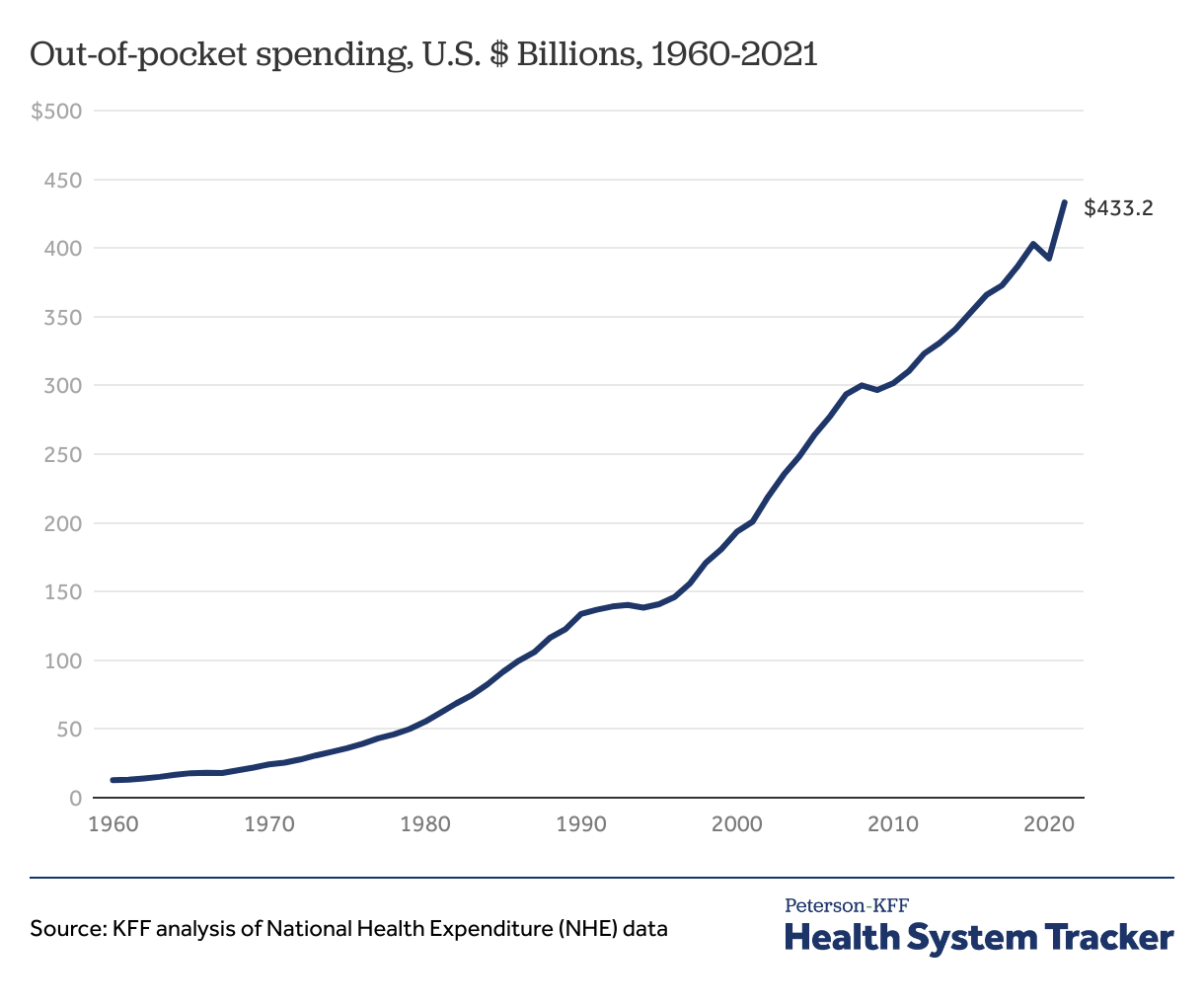

As with overall health costs, there has been a similar rise in out-of-pocket spending in recent years. Americans spent a total of $433 billion out of their own pockets on healthcare in 2021, an increase of more than 10.4% from the $392 billion spent the previous year. Out-of-pocket spending had fallen in 2020, primarily driven by the drop in utilization of health services when social distancing recommendations were put in place early in the pandemic. However, as healthcare utilization rebounded, so did out-of-pocket spending.

Out-of-pocket spending grew 10.4% between 2020 and 2021

Higher health costs in the U.S. leave Americans paying more out-of-pocket at the point of care ($1,315 per person) than people in peer nations ($825 per person), on average.

Patient cost-sharing responsibility, particularly for people with serious conditions, can quickly add up. For example, out-of-pocket costs for inpatient COVID-19 admissions among people with large employer coverage averaged $1,880 in 2020 (for admissions with at least some cost-sharing). Large employer plan enrollees’ emergency department visits cost $646 out-of-pocket, on average. Privately insured women who give birth pay almost $3,000 more out-of-pocket than women their same age who don’t give birth. Among privately insured people with large employer insurance, 1 in 5 taking insulin pay over $35 monthly.

While cost sharing is intended to encourage patients to make cost-effective decisions, it can also make care prohibitively expensive. Even though the vast majority of Americans have health insurance, 1 in 10 adults in the U.S. either delayed care or did not get care due to cost. Hispanic people in particular were more likely to be impacted by cost-related barriers to care, experiencing higher rates of delaying or not getting medical care and higher rates of difficulty paying medical bills. People with incomes below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) are also more likely to delay or go without medical care due to costs than those with higher incomes.

Out-of-pocket costs can also send American families, many of whom are living paycheck to paycheck, into medical debt. Among multi-person households with private health insurance about a third do not have enough liquid assets to pay a typical deductible ($2,000), and half (51%) could not pay a high-deductible or out-of-pocket maximum ($6,000). Further, maximum allowable out-of-pocket limits have grown much faster than wages and salaries under some private health plans.

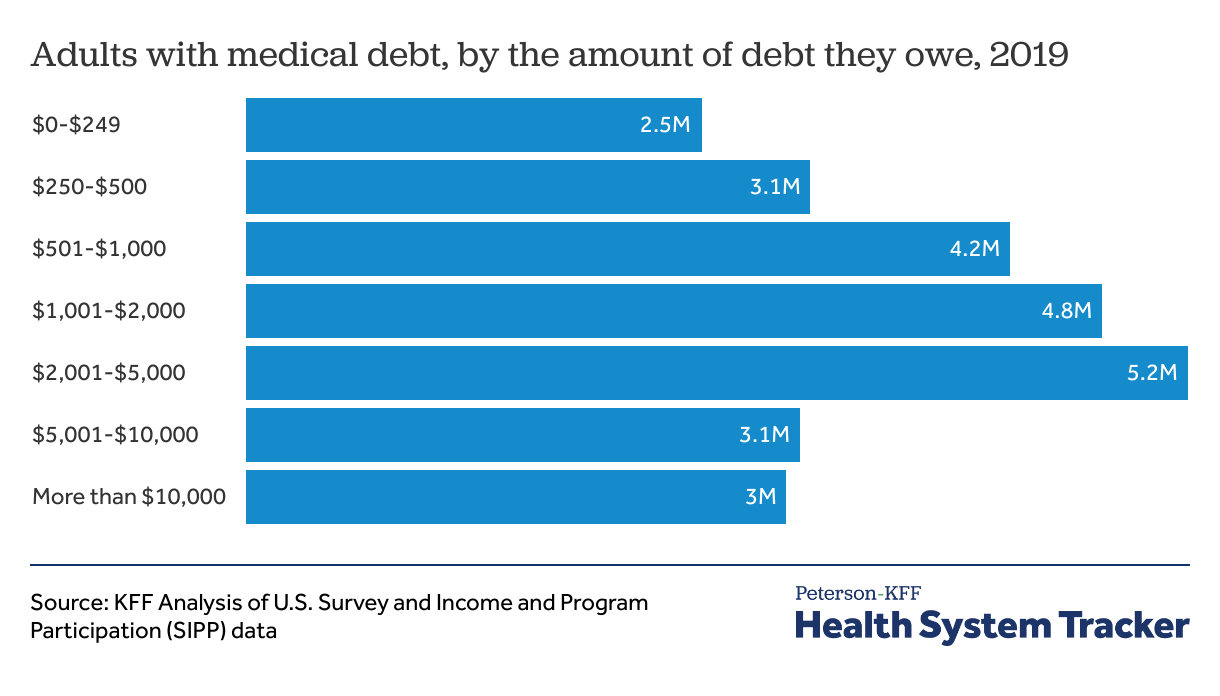

Using federal survey data, we estimate people in the U.S. owed at least $195 billion in medical debt in 2019, and most people with medical debt owed over $1,000. The burden of medical debt is experienced disproportionately by people of color. For example, a higher share of Black adults reported having medical debt than any other race or ethnicity group. People of color remain more likely to be of lower income, living in a Medicaid non-expansion state, and uninsured—all of which contributes to their higher medical debt rate.

23 million people in the U.S. owe a total of at least $195 billion in medical debt

Discussion

The coronavirus pandemic has had a profound effect on Americans’ health, and its impact on the health care system will likely last beyond the acute stage of the pandemic. The pandemic has shortened life expectancy in the U.S. and exacerbated health disparities and health access barriers. Although out-of-pocket spending dropped in 2020, this was primarily driven by lower utilization of non-COVID-19 care amid social distancing. As healthcare use has rebounded more recently, out-of-pocket spending has grown sharply relative to 2020.

Looking ahead to 2023, there are several challenges the U.S. health system is likely to face in the coming year. First, the pandemic is not over. Although death rates are not at their peak and vaccines have prevented countless deaths, COVID-19 is on track to once again be the third leading cause of death in 2022. The uptake of booster shots – needed to maintain a robust immune response against the virus – has been low, even among those most at risk.

Utilization of healthcare is rebounding after having been suppressed in the early pandemic, but health sector employment remains below expected levels based on pre-pandemic trends. Telemedicine has opened new pathways to access care, particularly to meet mental health needs, but it is not a replacement for in-person care and does not alleviate the strain on providers.

Although health coverage rates have improved with pandemic-related federal initiatives in recent years, many people will lose Medicaid when pandemic continuous coverage ends, as eligibility redeterminations resume in 2023. Additionally, as federal pandemic emergency funds run out and the Public Health Emergency ends, COVID-19 vaccines, tests, and treatments are likely to become more costly for some individuals (particularly the uninsured and under-insured) and for society more broadly.

Finally, health costs continue to rise, and health spending is representing a growing share of the U.S. economy and families’ budgets. Many American families lack the financial resources to afford typical out-of-pocket costs in private health plans. There have been some federal policy responses to address the cost of care for patients and public programs. For example, the No Surprises Act prohibits balance billing and sets an arbitration process for payments in case plan and provider negotiations fall through. And the Inflation Reduction Act will limit the growth in drug spending, as well as eventually allow negotiations in Medicare pricing for certain drugs. These measures are relatively narrowly focused, but could open the door for future policymaking addressing the underlying cost of care.

The Peterson Center on Healthcare and KFF are partnering to monitor how well the U.S. healthcare system is performing in terms of quality and cost.