Employer-based coverage is the most common source of health insurance for non-elderly Americans. The cost of employer sponsored health insurance—including premiums, deductibles, and other out-of-pocket costs—has risen steadily over time. Few employer plans (just 6% of firms with 200 or more workers in 2024) have programs to help lower-wage workers meet cost-sharing obligations. Low-income workers offered health insurance through their employer are typically not eligible for subsidies on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplaces, even if they would face lower costs to buy coverage and with reduced cost sharing. While many employers pay a significant portion of health insurance premiums, some workers face relatively high contributions to enroll in coverage, particularly when enrolling dependents. Employer health plans can then expose low and moderate-income families to thousands of dollars for premium contributions and cost-sharing, which can lead to medical debt. Many Americans, even those with private health insurance, do not have enough liquid assets to meet deductibles or out-of-pocket maximums.

This brief uses the Current Population Survey to look at the share of family income people with employer-based coverage pay toward their premiums and out-of-pocket payments for medical care. It considers non-elderly people living with one or more family members who are full-time workers and have employer-based coverage.

People in lower-income families with employer coverage spend a greater share of their income on health costs than those with higher incomes, and that the health status of family members is associated with higher health-related expenses.

Compared to higher-income people, those with lower incomes spend a significantly higher share of their income on health premiums and out-of-pocket expenses

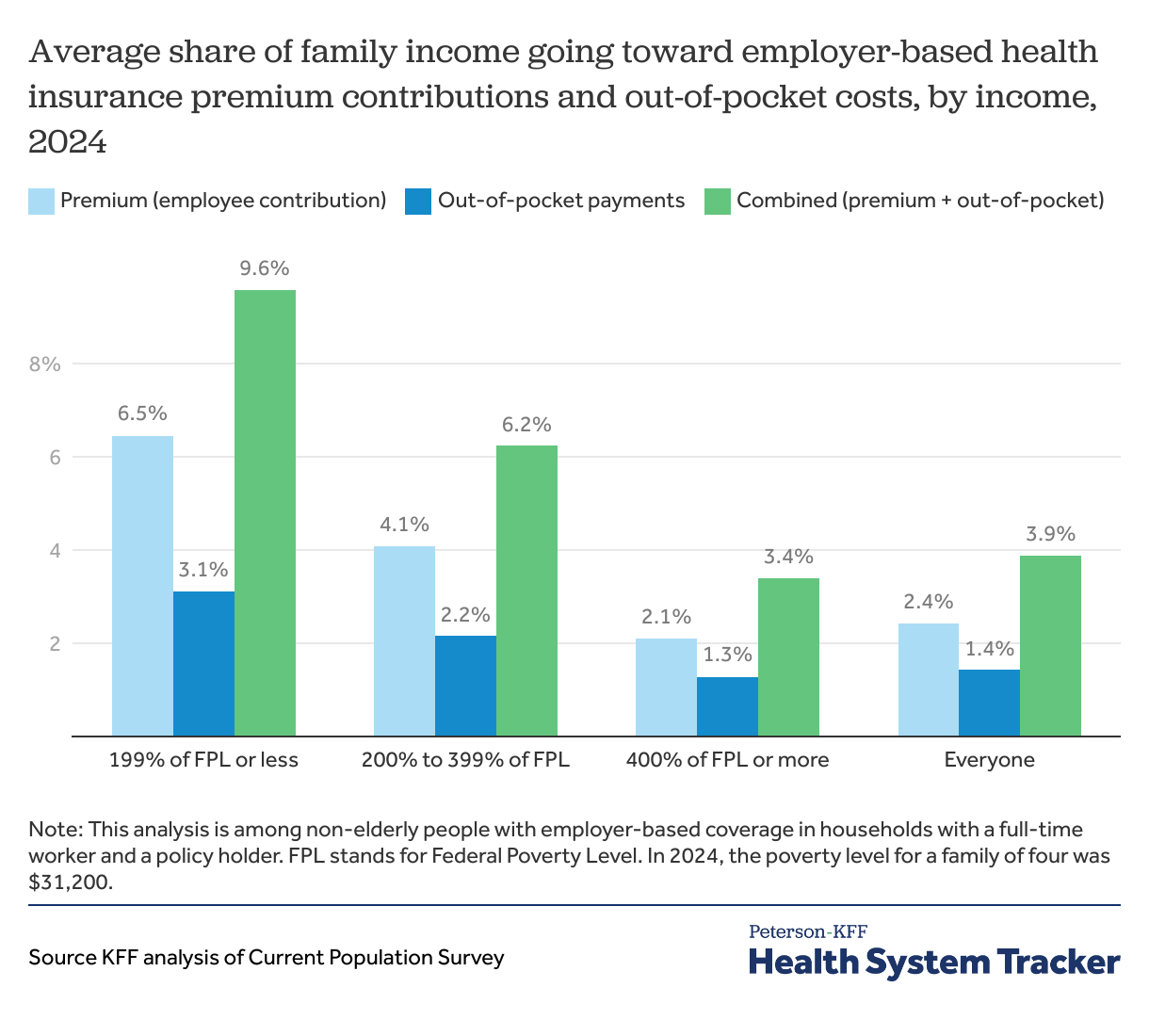

Individuals in families with employer coverage spend 2.4% of their income on the worker contribution to enroll in employer-based coverage and another 1.4% of their income on out-of-pocket spending such as the cost sharing typically required when enrollees use services. Overall, almost four percent of a family’s income goes to health insurance costs.

The share of family incomes spent on health insurance premium contributions and payments for medical care vary considerably by income for families with employer-based coverage. For those in families with incomes at 199% of federal poverty and below, the average family payments for health insurance premiums and medical care is 9.6% of family income. A substantial share (about two thirds) of that spending is for the premium contributions. Families with incomes between 200% and 399% of poverty spend an average of 6.2% on insurance premiums and medical care. Meanwhile, those in families with incomes at or above 400% of the federal poverty level pay about 3.4% of their family income on premium contributions and medical expenses.

Read more from

Employer-based coverage affordability

Families with at least one member in worse health spend a larger share of their income on medical expenses compared to those in better health

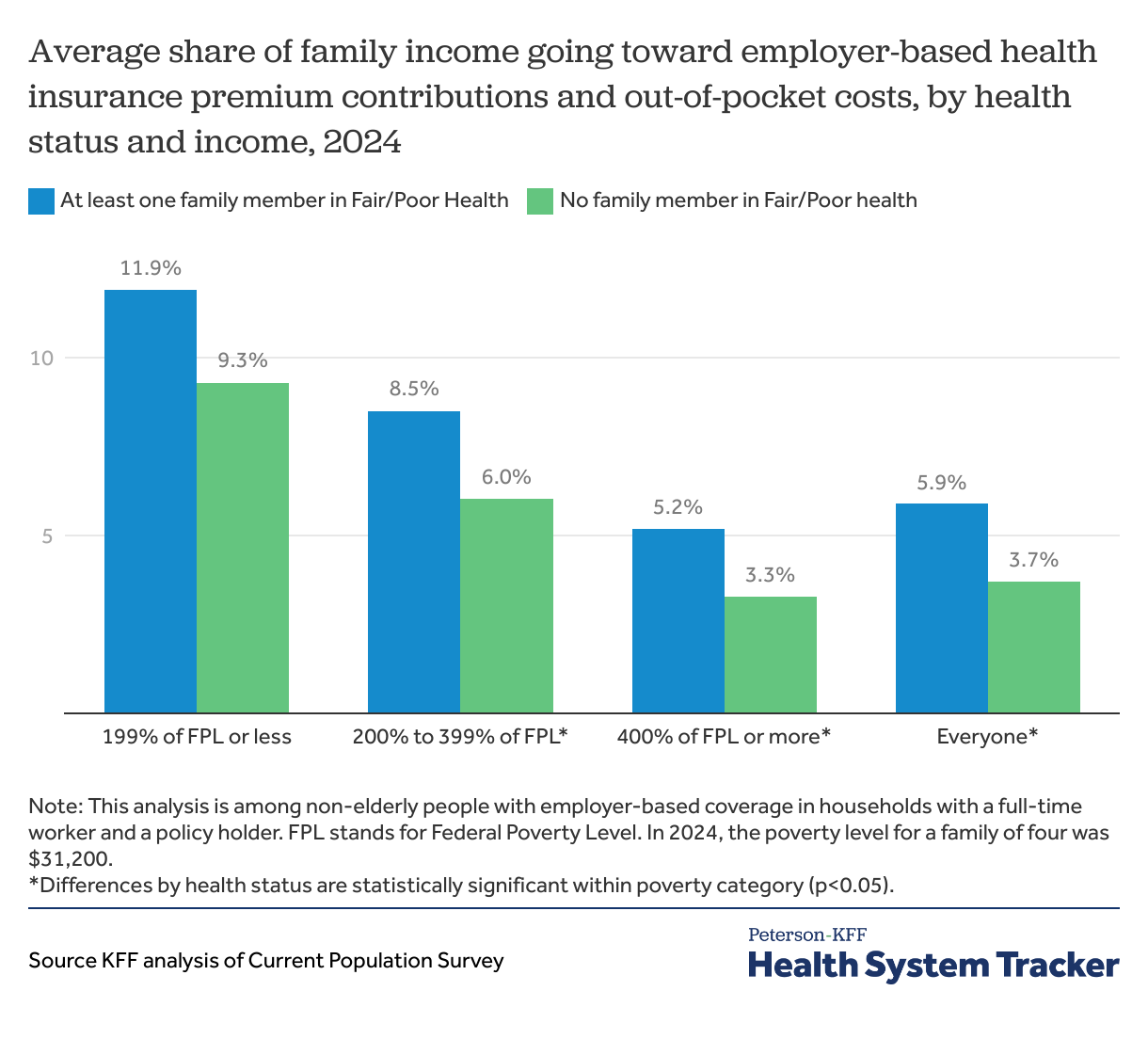

Living with someone in fair or poor health adds significantly to family health care spending, even for people with employer-based coverage. People with employer coverage often face a deductible which may require the enrollee to spend thousands of dollars before the plan covers most services. These differences can be seen by comparing the share of family income spent on premiums and out-of-pocket medical spending, between households where everyone covered by employer coverage reported being in better health (good, very good, or excellent health) to those with at least one member in worse health (fair or poor). Families with all members in better health spend 3.7% of their income on premium contributions and out-of-pocket medical expenses compared to 5.9% in households with at least one member in fair or poor health. However, this differs by family income. Families with incomes between 200 and 399% of federal poverty spent 8.5% of their income on health insurance if they had a family member in fair or poor health, compared to only 6% in a family without.

Insurance affordability in the private market

The cost of employer-sponsored health insurance has been steadily increasing over the past decade; premiums have grown 24% in the last five years, though deductibles have remained steady. More workers are covered by health plans with high-deductibles that may act as barriers to care, especially for lower-incomed workers.

Over time, as the total cost of employer coverage has risen, the share of people with employer-based coverage has fallen among those with lower and moderate incomes, but has remained fairly stable for people with incomes above 400% of poverty. Prohibitively high costs to enroll in employer coverage or afford medical expenses creates access barriers to enrolling in coverage and affording medical care or prescription drugs, putting Americans at risk of financial instability and medical debt.

The employer-based coverage affordability requirement has been a long-standing issue under the ACA. The ACA requires employers with more than 50 employees to offer full-time workers with health coverage that meets standards for affordability and minimum benefits. Employers that do not meet these standards are required to pay a tax penalty. Coverage is considered affordable if the contribution required for employee self-only coverage is less than 9.5% of that employee’s household income in 2025.

Methods

The Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) to the Current Population Survey provides information about employment, income, health coverage and demographic characteristics of people living outside of institutions in the US. Beginning in 2011, the ASEC began collecting information from respondents on the amounts they pay for health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket costs for medical care, which we use to measure average spending by people at different levels of poverty. The 2024 ASEC analysis includes non-elderly people with employer-based coverage in households with a full-time worker and a policy holder. We exclude people who report other types of coverage, therefore some households may have more health spending than reported here.

The ASEC asks respondents about coverage at the time of the interview. These findings are representative of 138 million non-elderly people with job-based coverage, including 9 million with family incomes of less than 200% of the Federal Poverty Level, and another 36 million with incomes between 200 and 400 percent of poverty. A “family” is related people living in the same household. Subfamilies are considered part of one family. The analysis does not include out-of-pocket spending on over-the-counter items as spending for medical care. The analysis does not consider potential tax deductions that may be available for premium contributions or out-of-pocket medical spending.

The Peterson Center on Healthcare and KFF are partnering to monitor how well the U.S. healthcare system is performing in terms of quality and cost.