The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires most private health plans to cover in-network preventive services at $0 cost-sharing for enrollees. Preventive services covered without cost-sharing include screening tests and assessments, immunizations, behavioral counseling, contraceptives, and medications that can prevent the development or worsening of diseases and health conditions.

Private health plans are required to cover preventive services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) with an “A” or a “B” rating, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), or the HRSA-sponsored Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI). These requirements apply to fully insured and self-insured health plans in the individual, small group, and fully and self-insured large group markets, except those that maintain “grandfathered” status.

This preventive services mandate is currently being challenged in federal court in Braidwood Management v. Becerra. On September 7, 2022, the U.S. District Court in the Northern District of Texas held that the ACA’s delegation to USPSTF is unconstitutional and the requirement to cover pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV violates the plaintiffs’ religious rights. The Court did not issue a remedy for the ruling, and as such, the preventive services coverage requirement remains in effect. The final briefs about the remedy were submitted to the court at the end of January 2023, and a decision is expected soon. While we know the district court will issue a remedy regarding the services recommended by USPSTF, it is not yet clear how broadly the ruling will apply. The parties will likely appeal, and it is expected that the plaintiffs will continue to challenge all the ACA’s required preventive services recommended by USPSTF, as well as HRSA and ACIP.

This analysis looks at the share of privately insured people who received ACA preventive care (service or medication). We use two claims databases to assess utilization of preventive care: Merative MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters dataset for large group enrollees and the Enrollee-Level External Data Gathering Environment (EDGE) Limited Data Set (LDS) for individual and small group market enrollees. As some preventive care is only recommended for people of a certain age, sex, or with a given diagnosis, we limit the analysis to services and prescriptions meeting these criteria, using definitions of preventive care from a large insurer.

Because the preventive care criteria we obtained for this analysis are from 2018, we merged these criteria onto 2018 claims data. As we discuss more below, preventive services utilization changed during the pandemic, as many people delayed or went without routine screenings in 2020 and most adults received COVID-19 vaccines in 2021. By late 2022, uptake of updated COVID-19 boosters was low and concentrated among older adults, who are disproportionately on Medicare and more likely to receive other (non-COVID) preventive care, too. Though much has changed since 2018 and the outlook of the pandemic is difficult to predict, we think our use of pre-pandemic data to assess the share of privately enrolled adults accessing any preventive care is more reflective of preventive care utilization in a typical year than more recent years of data would be. To the extent some privately insured people who otherwise receive no preventive care do get COVID-19 vaccines (including boosters) under the preventive services requirement, our estimates are conservative.

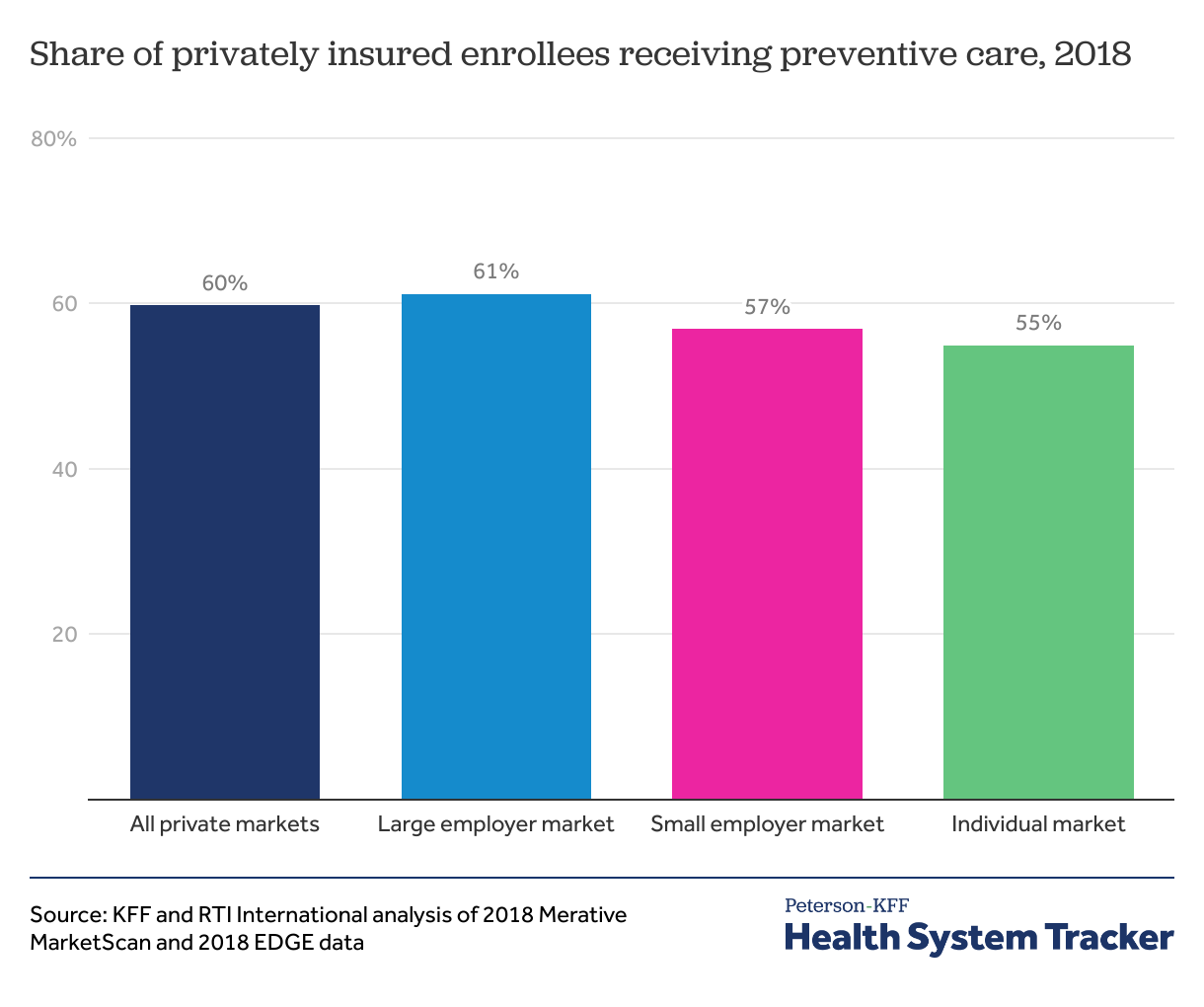

We find that 6 in 10 privately insured people (60%) received some ACA preventive care in 2018. Women, children, and older adults were more likely to have received preventive care. According to the American Community Survey, 173 million non-elderly people have private health insurance coverage. Based on this, we estimate roughly 100 million privately insured people got preventive care under the ACA in 2018.

6 in 10 privately insured people receive ACA preventive care in a typical year Share on XAbout 6 in 10 privately insured people received ACA preventive care in 2018

Similar shares of people who get their coverage through a large employer (61%), fully insured small employer (57%), and the individual market (those purchasing health coverage directly through ACA Exchanges or health plan websites) (55%) got preventive care.

The most commonly received preventive care includes vaccinations (not including COVID-19 vaccines), well woman and well child visits, and screenings for heart disease, cervical cancer, diabetes, and breast cancer. Some of these common preventive services are recommended by the USPSTF, while others are recommended by ACIP or HRSA.

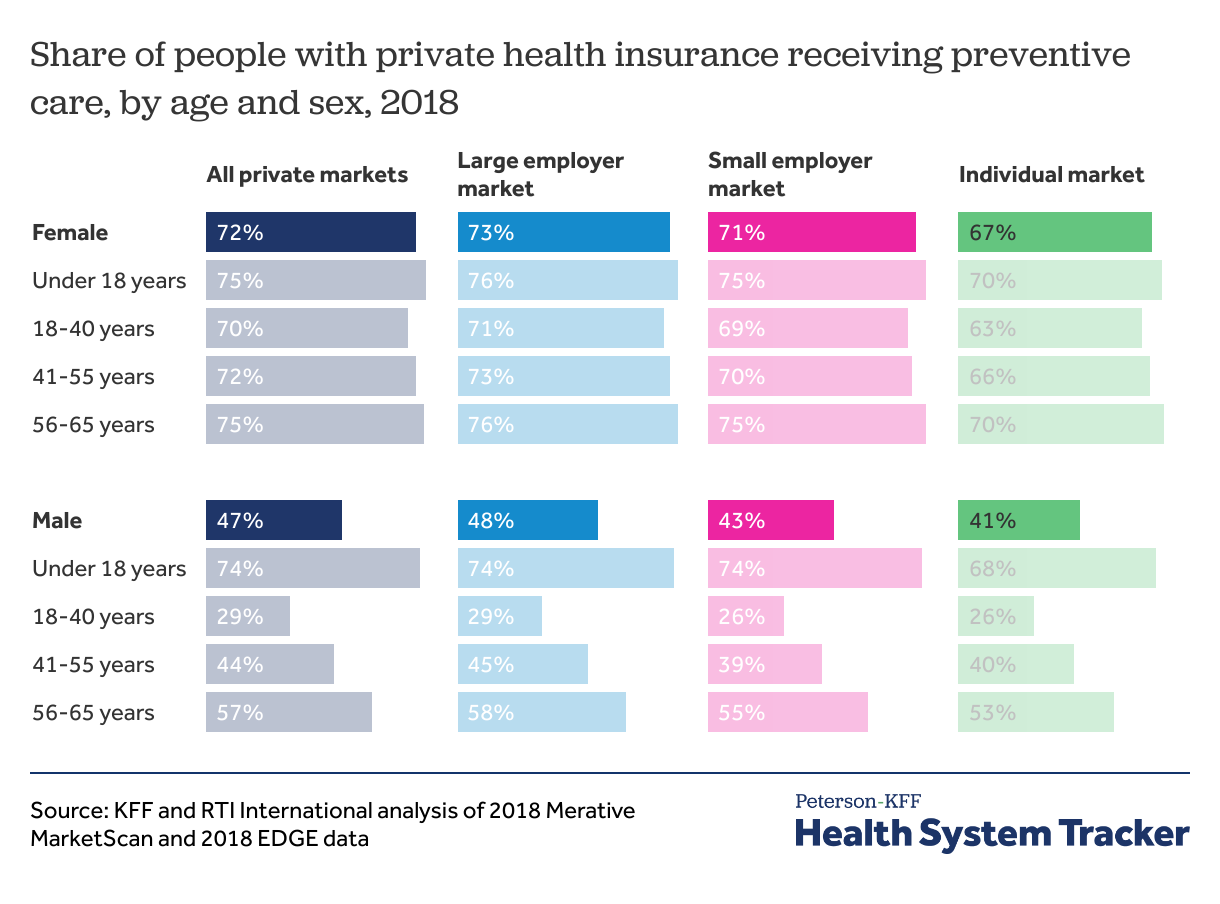

Women, children, and older adults are more likely to receive ACA preventive care

Many ACA preventive services are recommended only for specific groups of people, such as based on age or gender. For example, mammograms are recommended for women ages 50 to 74, while many vaccinations are recommended to young children. In this analysis, we look at the share of people receiving preventive care and do not limit the analysis only to those eligible for a service.

We find that about 7 in 10 children (ages 0-17) with private insurance accessed preventive care in 2018, with similar shares across boys and girls. A similar share, about 7 in 10, young women with private coverage use preventive care into adulthood, while young men use preventive care at far lower rates (about 3 in 10). In middle age, utilization of preventive care increases for men, but still at lower rates than for women. Again, this could be influenced by which preventive services are recommended for certain groups.

Discussion

In this analysis, we find about 6 in 10 privately insured people, or roughly 100 million people, received ACA preventive care in 2018. Some of these preventive services were recommended by the USPSTF, while others were recommended by other government bodies. Our findings suggest the outcome of the Braidwood Management v. Becerra case could have widespread implications for out-of-pocket costs and access to preventive care.

Currently, the preventive services coverage requirement remains in effect. It is not yet clear how broadly the district court’s remedy for the services recommended by USPSTF will apply, or what higher courts will decide on appeal. If the case makes its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, the implications of a final decision in favor of the plaintiffs would depend on the breadth and basis of that ruling.

Overturning any part of the ACA’s preventive services coverage requirement would leave coverage decisions to health plans. If not for the ACA’s preventive services coverage mandate, health plans would have discretion to apply cost-sharing for these services, which could include copayments, coinsurance, or deductibles. The cost of preventive services varies widely depending on the service. For example, the price of a flu shot might be roughly $50, while the price of a colonoscopy is often well over $1,000. Out-of-pocket costs could cause some to miss or delay care. Missed or delayed screenings could lead to later diagnoses of health conditions that might have been more treatable or less costly if caught earlier. If health plans shift out-of-pocket costs toward preventive care, though, that could result in other services having lower out-of-pocket costs or some health plans having slightly lower premiums.

This analysis reflects preventive care utilization in 2018, before the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, several studies documented a sharp decrease in use of routine care, including cancer screenings, as many people delayed or went without care due to concerns about COVID-19 Although use of healthcare generally has rebounded since the early pandemic, a substantial share of adults continued to report delaying or missing care due to the pandemic in 2021. Meanwhile, though, in 2021, most adults in the U.S. received COVID-19 vaccines, which qualify as ACA preventive care. (To date, all doses were purchased by the federal government and providers were prohibited from charging patients, regardless of their insurance status. However, providers could seek reimbursement for administration or visit costs from insurers, and largely because of the ACA’s preventive service requirements, private insurers were generally required to reimburse providers.)

Going forward, we might expect a return to pre-pandemic levels of preventive care utilization shown in this analysis. COVID-19 boosters and other new additions to the preventive services recommendations could have a small upward effect on the share of people receiving preventive care. However, uptake of the updated bivalent booster was low and concentrated among older adults, who are disproportionately covered by Medicare. Additionally, older adults enrolled in private coverage are more likely to receive other preventive care (e.g., flu vaccines and cancer screenings), in which case their receipt of a COVID booster may not meaningfully increase the share of people receiving an ACA preventive service. It is therefore unclear whether future COVID-19 boosters would meaningfully increase the share of privately insured people receiving preventive care, but to the extent they do have an upward effect, our estimates are conservative.

Note: Krutika Amin, Gary Claxton, Matthew Rae, Shameek Rakshit, and Cynthia Cox are with KFF. Brett Lissenden, Allison Carley, and Gregory Pope are with RTI International.

Methods

We used two claims databases as the foundation of this analysis. For large group employer health plans, 2018 Merative MarketScan claims data were used. To make MarketScan data representative of large group health plans, weights were applied to match counts in the Current Population Survey for enrollees at firms of a thousand or more workers by sex, age, state, and whether the enrollee was a policy holder or dependent. Weights were trimmed at eight times the interquartile range. For the individual and small employer group markets, Enrollee-Level External Data Gathering Environment (EDGE) Limited Data Set for 2018 was used. The 2018 EDGE data include masked enrollment and claims information for nearly 30 million enrollees in ACA-compliant individual and small employer group plans in all states and the District of Columbia. Enrollees 65 and older and enrollees with enrollment of 6 months or less were excluded from both MarketScan and EDGE data. The EDGE data do not include enrollees in grandfathered, association, or short-term plans, who may have different utilization patterns.

Preventive services were flagged in the MarketScan outpatient and EDGE medical files based on CPT/HCPCS codes, age/sex criteria, and if required, presence of a relevant diagnosis in the year. Preventive drugs were flagged in MarketScan and EDGE pharmacy claims files based on NDC codes, age/sex criteria, and if required, certain diagnosis codes in the year.

We were able to codify the criteria for preventive services from a large insurer in 2018 and apply those criteria to our EDGE and MarketScan claims databases. The algorithm to flag preventive services and drugs was developed based on a scan of preventive care recommended in 2018 and Cigna’s criteria. Enrollees with at least one preventive service flag were identified at the “enrolid”-level in MarketScan or “sysid”-level in EDGE.

For claims flagged based on preventive care recommendation groups and based on review of one insurer’s definition of preventive services, there are some claims we identify as ACA preventive services that still show cost-sharing. There is room for interpretation of the preventive services recommendations (e.g., frequency of screenings, prior authorization) so some insurers likely apply different guidelines. The inverse could also be true, and we may have missed some preventive services that other insurance plans do fully cover at no cost sharing. Even if we had every insurers’ definition of preventive care, we would not be able to match that definition to enrollees in the claims data because the datasets do not include the health plan name or plan design information.

The Peterson Center on Healthcare and KFF are partnering to monitor how well the U.S. healthcare system is performing in terms of quality and cost.