Most major commercial insurers offer enrollees access to digital health tools such as remote monitoring. As access and use expand, there are important questions as to who is receiving these services, for the management of what conditions, for how long, and how much they cost.

Remote monitoring includes remote physiologic monitoring (RPM), whereby a patient’s physiological data, including their weight, blood glucose, or blood pressure measurements are sent to a clinician for review and action, and remote therapeutic monitoring (RTM), where most commonly a patient’s self-reported data such as their pain or activity levels, are shared with and monitored by a provider.

This analysis examines patterns in outpatient RPM and RTM use among adults under 65 with employer coverage using Merative™ MarketScan® Commercial Databases. This analysis includes claims for 10.2 million adult under 65 with at least six month of coverage. This total is weighted to 102 million of the 165 million people with employer coverage. Claim-level diagnoses are categorized by Clinical Classification Software-Refined (CCSR) to understand which conditions the services are being used to treat or evaluate.

In 2023, an estimated 300,000 adult enrollees with employer-sponsored health insurance received at least one remote monitoring claim, representing 0.3% of all adult enrollees with six or more months of coverage. Of the enrollees with any remote monitoring, 93% had any RPM claims and 19% had any RTM claims. Some enrollees used both RTM and RPM. Enrollees with RPM claims were most likely to have diagnoses monitoring for circulatory conditions (47% of all enrollees with any RPM claims) or treating hypertension and circulatory diseases (31%). Most enrollees with RTM claims had diagnoses for the management of musculoskeletal disorders (73%). Payments for these services vary, with an average monthly cost per patient of $55 for RPM and $78 for RTM.

Commercial payers vary widely in their coverage of RPM and RTM services and sometimes restrict which conditions are eligible for coverage as well as impose limits on the duration of coverage for enrollees. Traditional Medicare, in comparison, offers more expansive coverage of remote monitoring services and places fewer restrictions on who may use these services. Under Traditional Medicare, RPM may be used for any acute or chronic condition, and RTM may be used for respiratory care, musculoskeletal care, or behavioral health care. Despite stricter coverage rules in commercial, utilization patterns of remote monitoring services, including duration of use and for what conditions, remain similar to Medicare.

Who uses RPM and RTM among adults with employer-sponsored insurance?

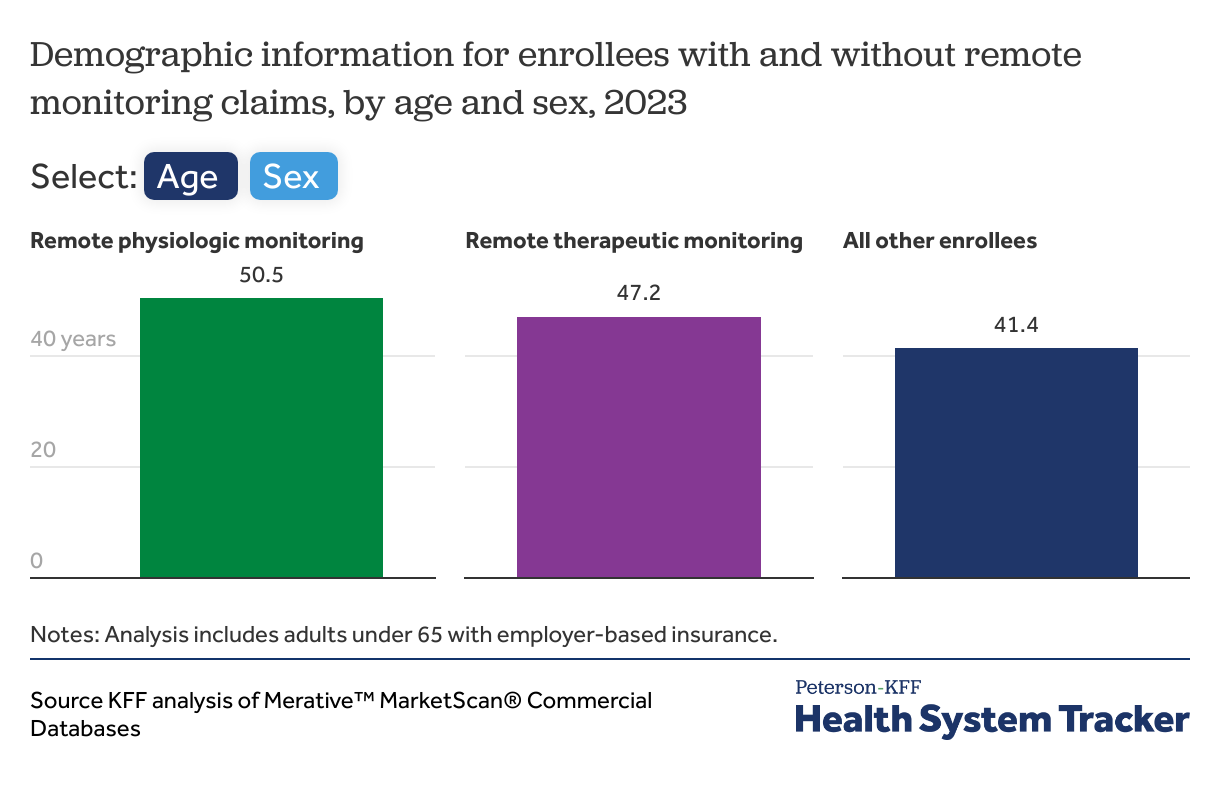

Enrollees who use remote monitoring are mainly older and more likely to be female.

Compared to enrollees who did not use remote monitoring services, those who used remote monitoring were older— with an average age of 51 for RPM and 47 for RTM— compared to 41 for those who did not use these services. Remote monitoring users are also more likely to be female.

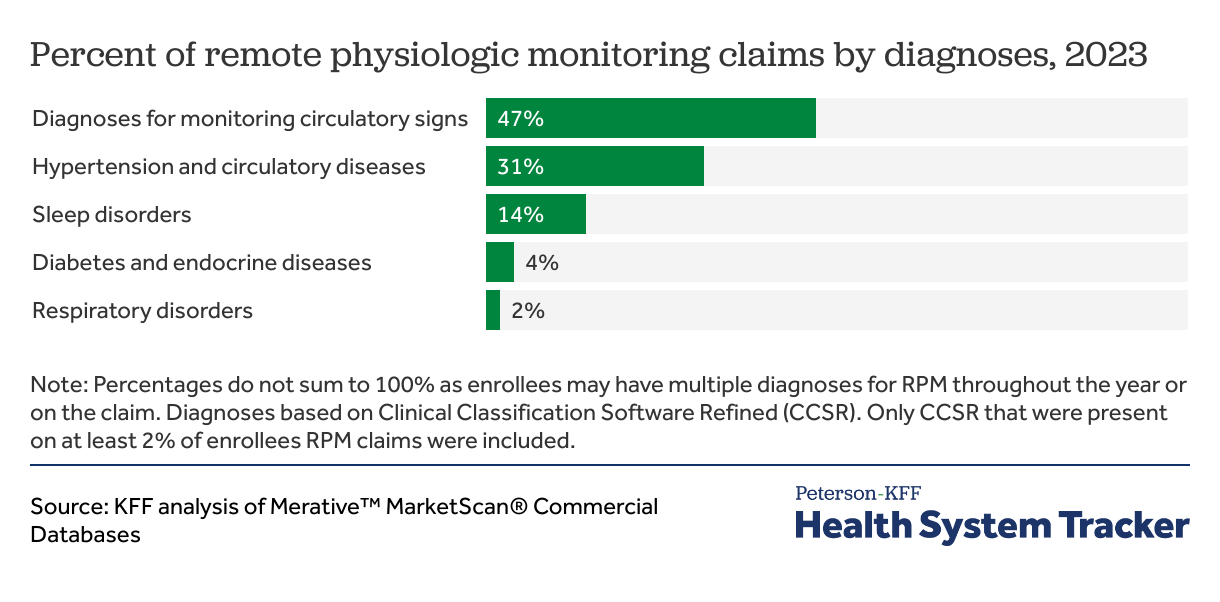

Remote physiologic monitoring is most commonly used for monitoring circulatory signs (47%) or treating hypertension and circulatory diseases (31%).

Most enrollees using RPM services had diagnoses indicating monitoring for circulatory signs (47%), or hypertension and circulatory diseases (31%). Another 14% of enrollees had sleep disorder diagnoses. Monitoring for diabetes was less common among enrollees. Other diagnoses not listed here make up about eight percent of claims and five percent of enrollees.

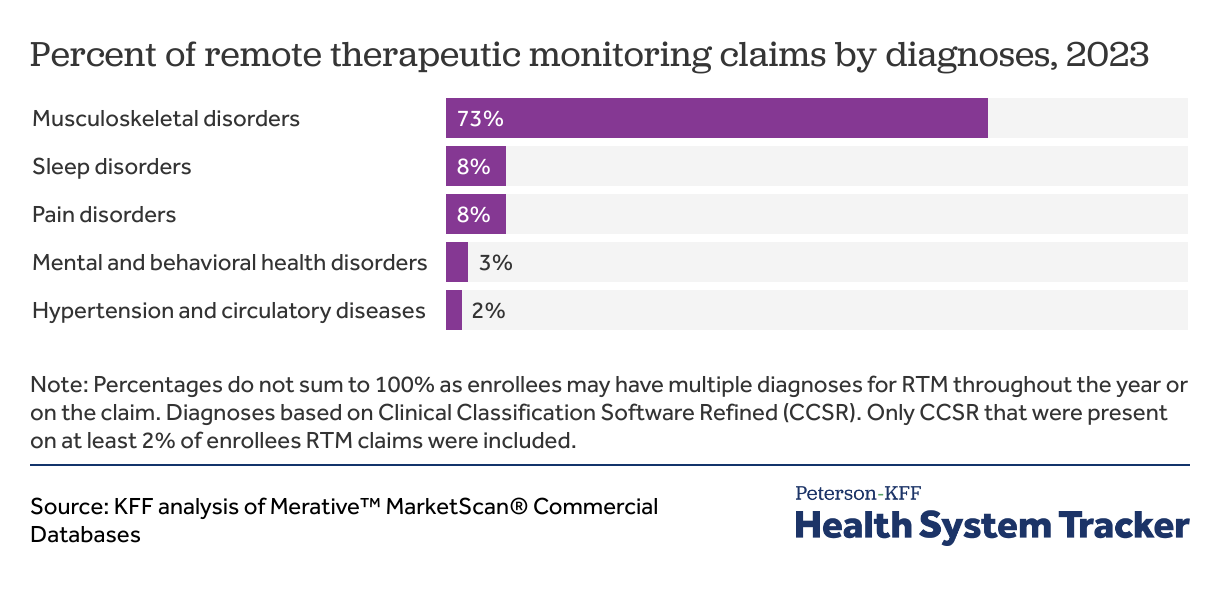

Remote therapeutic monitoring is most often used for musculoskeletal disorders (64%).

Enrollees receiving RTM services are most likely to have diagnoses of musculoskeletal disorders (73%), followed by sleep disorders (8%) and central nervous system pain disorders (8%). Other diagnoses not listed here make up about 11% of RTM claims and 12% of enrollees with RTM claims.

How long do enrollees use RPM and RTM services?

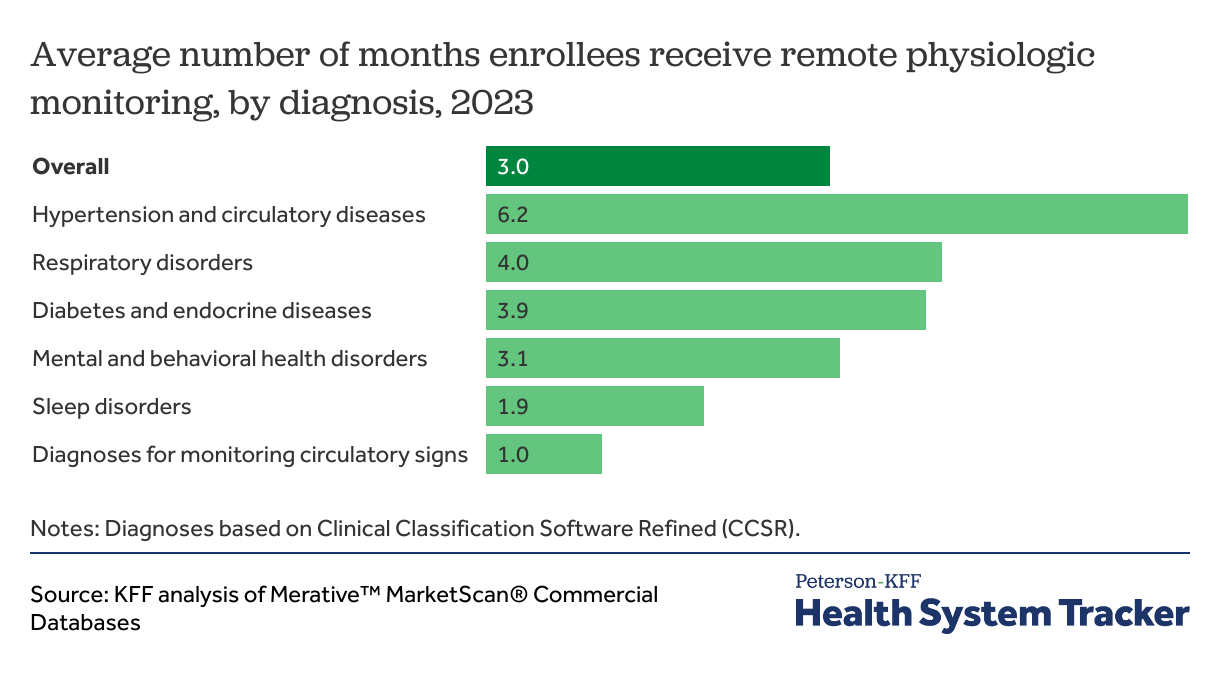

On average, remote physiologic monitoring for hypertension and other circulatory diseases lasts about 6 months. Monitoring for other diagnoses is shorter.

Patients with hypertension and circulatory diseases, making up about one third of all patients, receive remote physiologic monitoring for six months out of the year on average, notably longer than the overall average duration (3.0 months). Patients with respiratory disorders, which was far less common, receive an average of 4.0 months of RPM services out of the year. Despite some people receiving several months of treatment, many enrollees receive only one month of RPM.

Use of remote physiologic monitoring for diagnoses related to monitoring circulatory signs was common, and allows clinicians to identify if patients have a circulatory disease. These uses averaged only one month of monitoring of patient-generated data to support clinician and patient decision making. Using RPM for managing and treating existing diseases, such as diabetes, lasted for a longer duration of 6.2 months. There is some efficacy in using RPM for managing diabetes, but interventions less than six months have been found more beneficial.

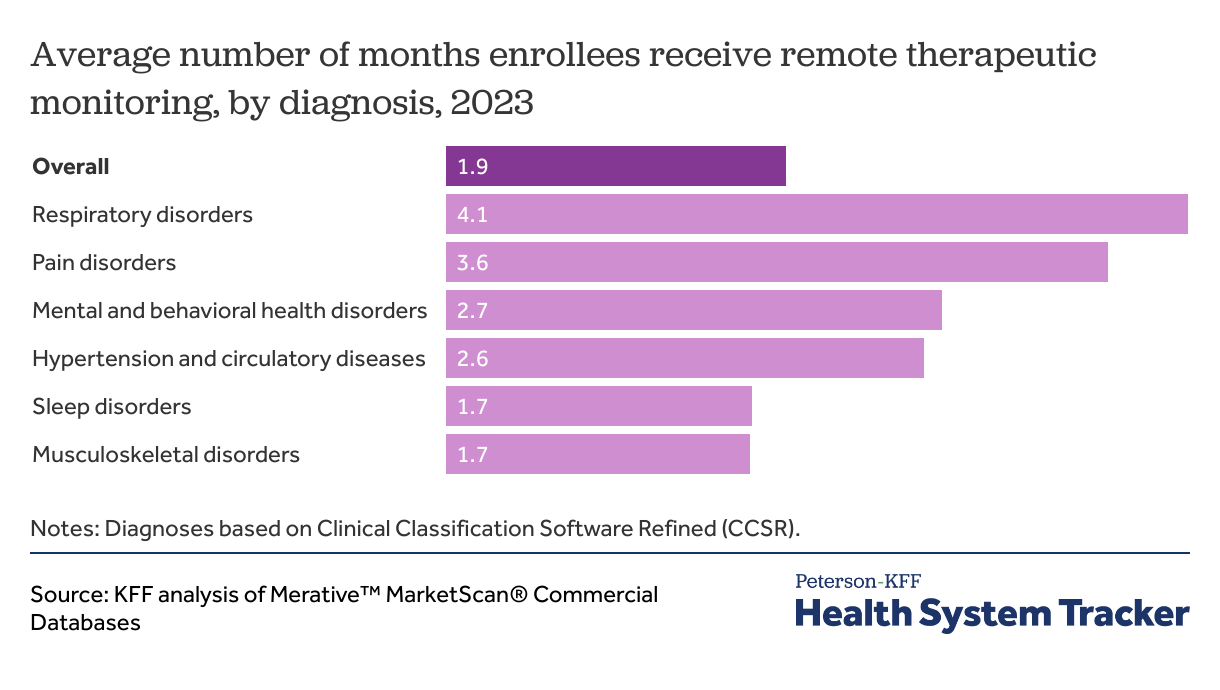

Remote therapeutic monitoring lasts two months on average but differs based on the reason for treatment.

Almost three in four enrollees with RTM used it to monitor musculoskeletal disorders which lasted for an average of 1.7 months. The longest duration was among patients with respiratory disorders, with an average of 4.1 months out of the year, followed by pain disorders averaging 3.6 months in length. Most other diagnoses have shorter treatment, with an average duration across all diagnoses lasting 1.9 months out of the year.

How much is spent on remote monitoring?

RPM and RTM services include the same three components: device supply, device set-up and education, and treatment management. Reimbursement for device set-up and education can only be billed in the first month of remote monitoring treatment in Medicare and under private insurance. Device supply and treatment management codes may be billed every month of treatment, with add-on codes for incremental time spent on treatment management. All three components of remote monitoring may be billed during the first “set-up month,” and only two may be billed in subsequent “maintenance months.”

Commercial payers may utilize capitated or value-based arrangements rather than fee-for-service models to reimburse remote monitoring costs. A recent survey of digital health purchasers found that nearly half of employers, health plans, and health systems are currently using performance-based contracts and the majority plan to use them in the next year. These alternative payment models, along with variable coverage policies, may result in spending patterns in claims data that differ from those observed in Medicare.

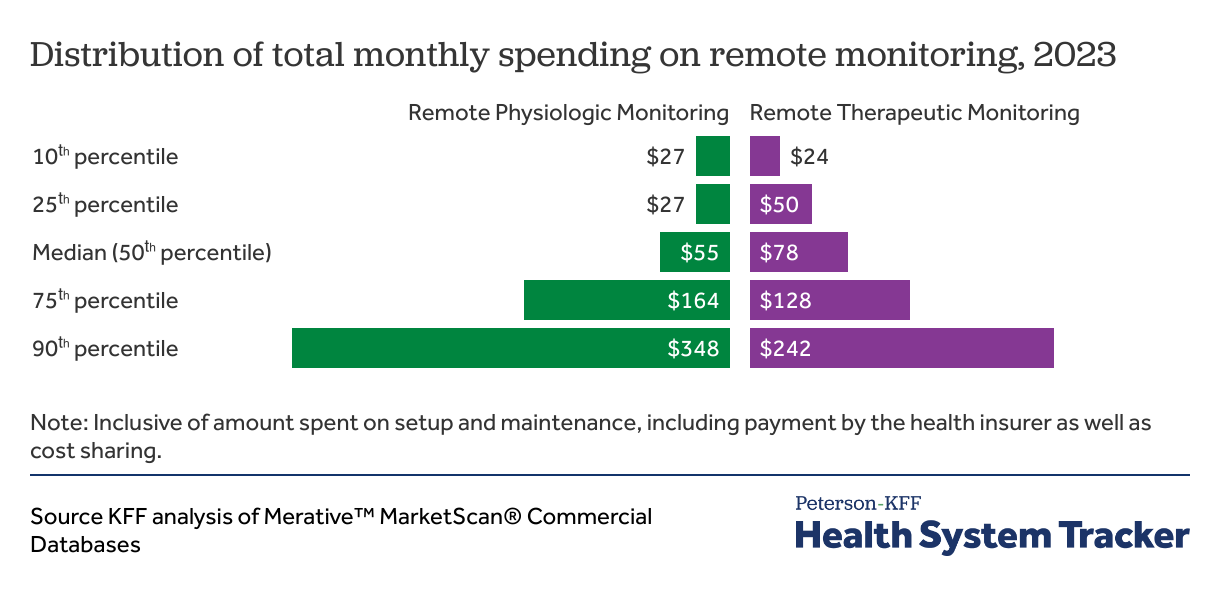

The median total monthly spending per patient is $55 for RPM and is $78 for RTM, though there is variation in how much is paid.

There is variability in the average monthly payment per patient for RPM and RTM. Most months of RPM have an average paid amount of $55 per patient, with 10% of months at less than $27 or more than $348. Similarly, remote therapeutic monitoring has a median monthly spending per patient of $78, but 10% of months are less than $24 and 10% cost $242 or more.

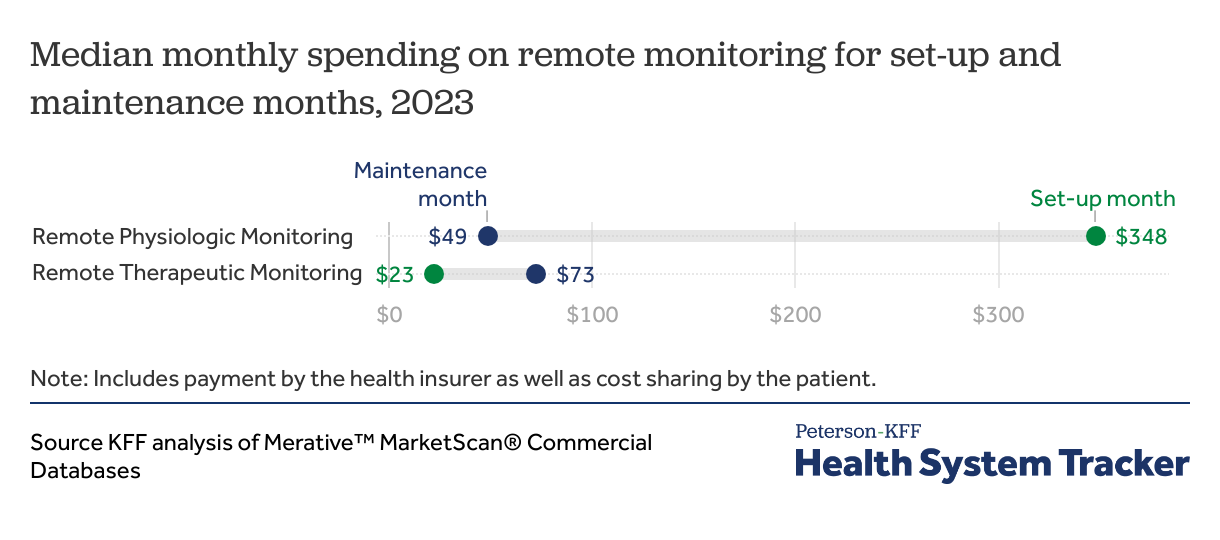

Set-up and maintenance months have different median monthly paid amounts per patient for RPM and RTM.

On average, spending on set-up months per patient for remote physiologic monitoring is significantly higher than maintenance months, with a median paid amount of $348. This is over six times as much as spending for maintenance months, which is $49 on average.

Remote therapeutic monitoring has lower spending for months with setup codes, with a median monthly setup payment of $23 per patient. Individual services are less expensive, on average, for RTM than for RPM, but RTM maintenance months end up being more expensive ($73) because they often include additional payments for treatment management, suggesting providers may be spending and billing more time interpreting RTM data. RTM payments may also be lower overall than RPM because RTM data can be self-reported by patients and often require fewer hardware devices.

What is the out-of-pocket cost for enrollees?

Enrollees only pay a small portion of remote monitoring in cost sharing through deductibles, copays, and coinsurance. The average monthly out-of-pocket cost per patient for remote physiologic monitoring is $12. The median out-of-pocket cost for remote therapeutic monitoring is $21 per month.

The relatively modest cost sharing amount for remote monitoring may be due to the service intensity that enrollees with remote monitoring may use within a year, so they often have met their annual deductible and out-of-pocket maximum.

Methods

Data comes from Merative™ MarketScan® Commercial Databases which contains claims for over 21 million people under 65, from which this analysis uses 10.2 million adult enrollees with at least six months of coverage. To make MarketScan data representative of enrollees in employer-sponsored health insurance weights were applied to match counts in the Current Population Survey by sex, age, and location to represent 165 million people in the U.S. population with this type of health coverage.

Remote physiologic monitoring includes any claim line with a Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 99453, 99454, 99457, 99458, and 99091. Remote therapeutic monitoring includes CPT codes 98975, 98976, 98977, 98980, and 98981. The setup codes include 99453 and 98975, and the monthly billable codes are 99454, 99457, 99458, or 99091 (RPM) and 98976, 98977, 98980, and 98981 (RTM). Diagnosis categories are based on any of the four available diagnosis codes on the outpatient claim line, which were then assigned to their relevant Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR) grouping. Hypertension CCSR codes include CIR007, CIR008, CIR036, PRG020. Diabetes and endocrine disorder CCSR codes include END002, END003. Musculoskeletal disorders CCSR codes include MUS001 through MUS038. Respiratory disorders include RSP001 through RSP017. Mental and behavioral health disorders include MBD002, MBD003, MBD004, MBD005, MBD006, MBD007, MBD008, MBD009, MBD010, MBD011, MBD012, MBD013, MBD014, MBD017, MBD018. Sleep disorders were included if they were categorized as CCSR NVS016, pain disorders included CCSR NVS019, and diagnoses for monitoring circulatory signs are categorized as CCSR SYM012.

Only outpatient claims were included in this analysis. Monthly costs were calculated by summing up all included claims as described above for each person, by month. Enrollees for whom all RTM and RPM claims were paid at $0 were filtered out. Medians are used for average costs due to the right-skewed distribution. Months enrolled were tallied across the year and not necessarily continuous.

Claims data available in MarketScan allows an analysis of liabilities incurred by enrollees with some limitations. First, these data reflect spending incurred under the benefit plan and do not include balance-billing payments that beneficiaries may make to health care providers for out-of-network services or out-of-pocket payments for non-covered services.

The analysis included all diagnosis on a claim, though these may not reflect the diagnoses for which the device was prescribed. The claim also does not include information about the type of device being used, or what it is monitoring. Claims were included only for the calendar year 2023, and would have missed setup costs in previous years.

In some cases, payers may use alternative payment models to pay for RPM or RTM; this analysis relies on claims and only captures individually enumerated services which include a billed cost. Enrollees with only zero-paid claims were filtered out due to the potential for alternative payment models.

The Peterson Center on Healthcare and KFF are partnering to monitor how well the U.S. healthcare system is performing in terms of quality and cost.