Health care spending is highly concentrated, with a small share of people accounting for a large share of expenditures during any year – just 5% of people are responsible for at least half of overall spending. This makes understanding and effectively managing the care for this group vital to improving the quality and efficiency of health care delivery.

People with persistently high health spending — 1.3% of all enrollees — had average per person spending of almost $88,000 and accounted for 19.5% of total spending in 2017 Share on XPeople with high health care spending are not a homogeneous group: some have very high spending during a short spell of illness, while others have ongoing high spending due to one or more chronic illnesses. The patterns and types of medical spending also vary among these high-need patients: for example, those with acute spells of illness are more likely to have high hospital spending while those with chronic illnesses spend more on outpatient services and prescriptions. Those with persistently high spending, while few in number, are some of the most expensive users of care – the 1.3% of enrollees with high spending in each of three consecutive years (2015-2017) had an average spending in 2017 of almost $88,000, accounting for 19.5% of overall spending that year. The predictability and extent of their spending suggest that any efforts to reduce the total costs of care and improve health system quality must focus heavily on this group of people.

This analysis looks at the amounts and types of health spending for people with employer-based health insurance who have continuing high health care spending. To do this, we used the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database (MarketScan) database, which has clinical and enrollment information for millions of workers and their dependents. We looked at the spending for a subset of enrollees with three consecutive years of coverage (2015-2017), which we refer to as “continuously covered enrollees.” We then identified those who were in the top five percent of spenders in each of the three years, which were refer to as “people with persistently high spending.” We show the inpatient, outpatient and prescription spending in 2017 for people with persistently high spending, and compare those to the spending for all continuously covered enrollees and for those with high spending just in 2017 but not in either prior year (“people with high spending just in the last year”). We also analyze enrollees’ diagnoses to identify the health conditions that are most highly correlated with being a person with persistently high spending.

The MarketScan database has a significant advantage for this type of analysis because it contains diagnostic and claims information for a large number of people who can be followed over several years. One important limitation for this analysis is that the claims data show the retail cost for prescription drugs and does not include information about the value of rebates that may be received by payers. Some prescriptions used by people with high spending may be accompanied by substantial rebates (e.g., insulin), while prescriptions for some other drugs, such as sole-source drugs may not result in any rebates to payers.

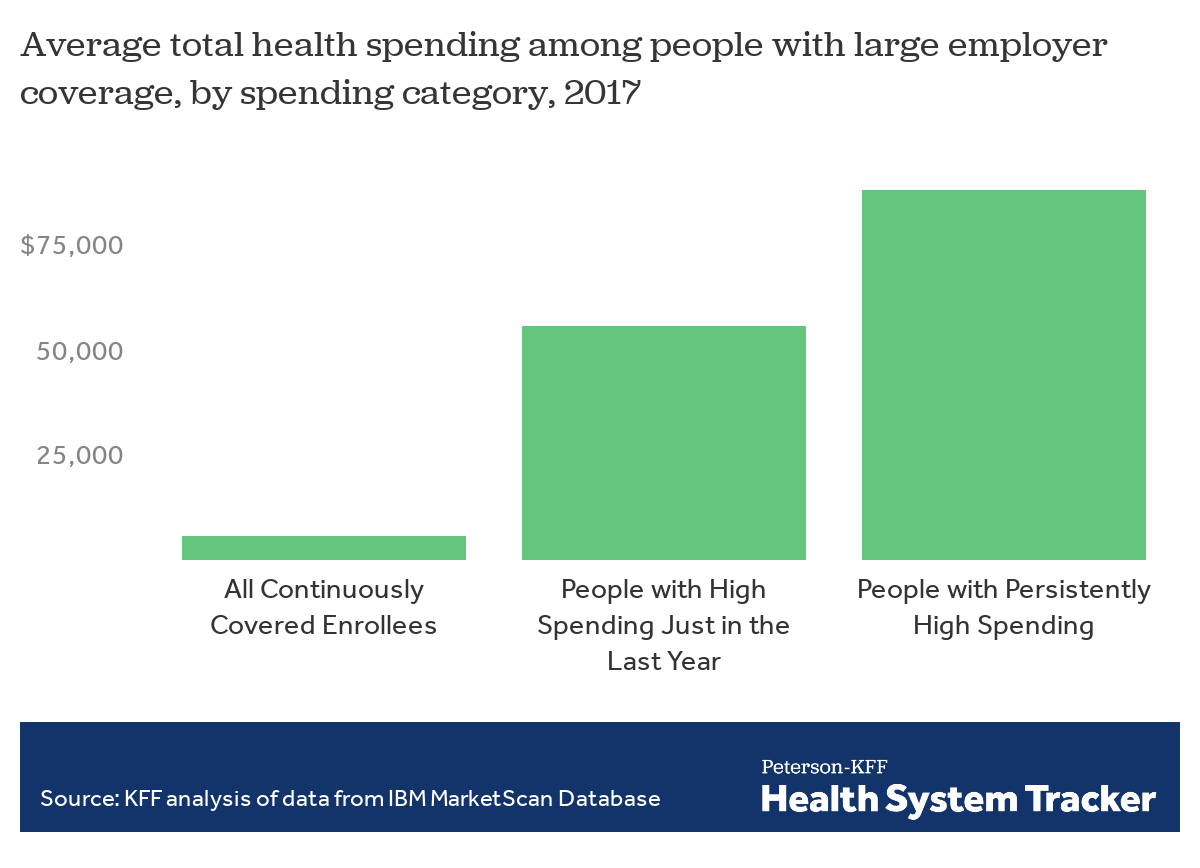

People with persistently high spending averaged almost $88,000 in total claims spending in 2017

People with persistently high spending averaged $87,870 in health spending in 2017, which is almost 60% higher than the average spending for people with high spending just in the last year (those with high spending in 2017 but not in previous years) of $55,670, and about 15 times more than the average spending for all continuously covered enrollees ($5,870).

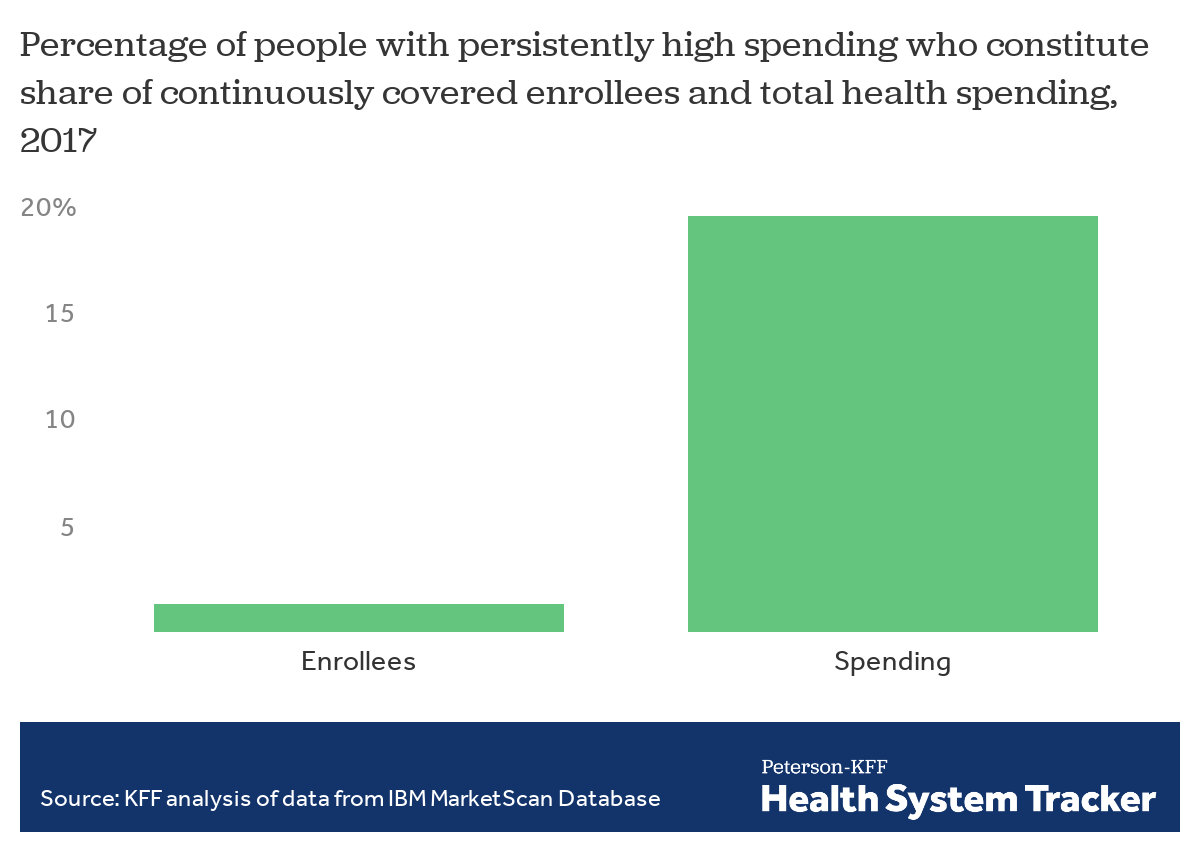

People with persistently high spending are a small share of enrollees but account for a large share of spending

While people with persistently high spending comprised only a small share of continuously covered enrollees (1.3%), they accounted for 19.5% of total spending in 2017 by the three-year group.

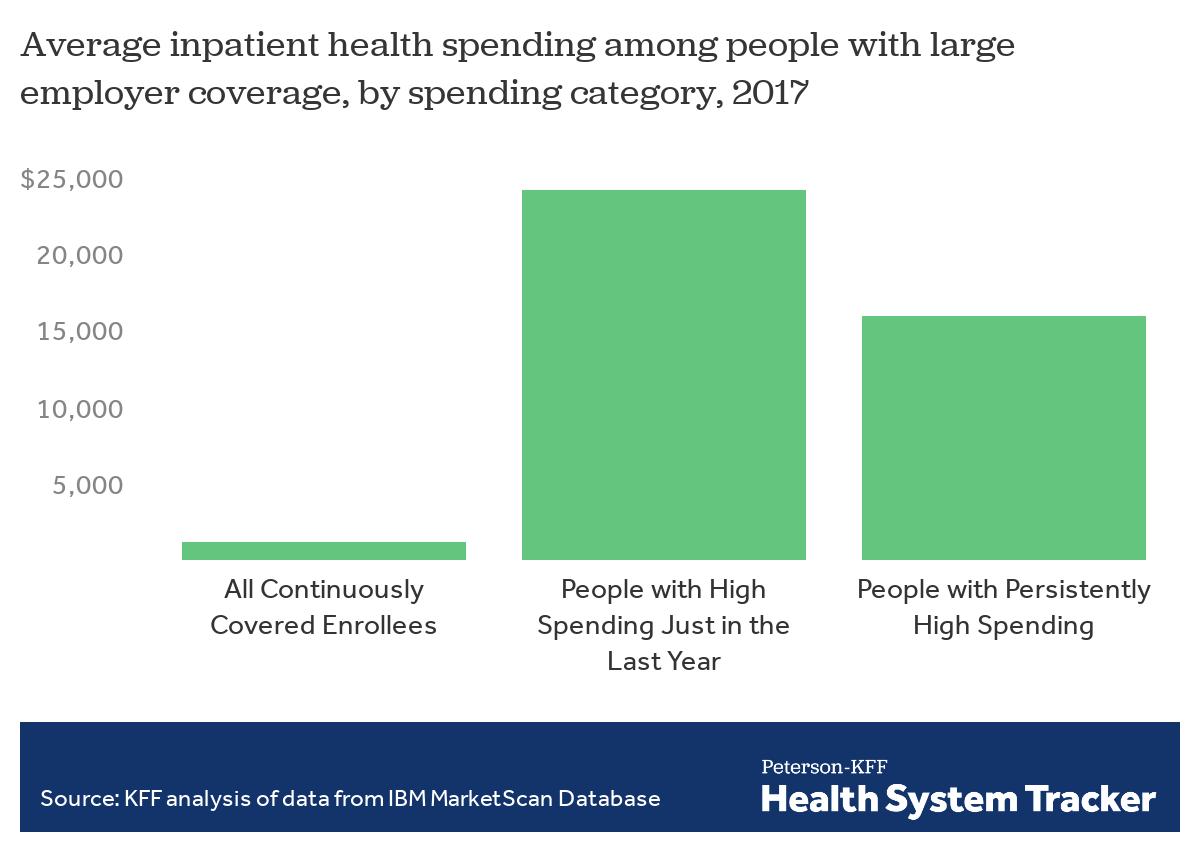

People with high spending just in the last year had higher spending for inpatient services

Although people with persistently high spending had higher overall average spending in 2017, people with high spending just in the last year spent more on average on inpatient services, $24,270 as compared to $15,970, likely related to the acute nature of their conditions. Both groups had average inpatient spending that was many times more than the overall average inpatient spending amount of $1,220 for all continuously covered enrollees.

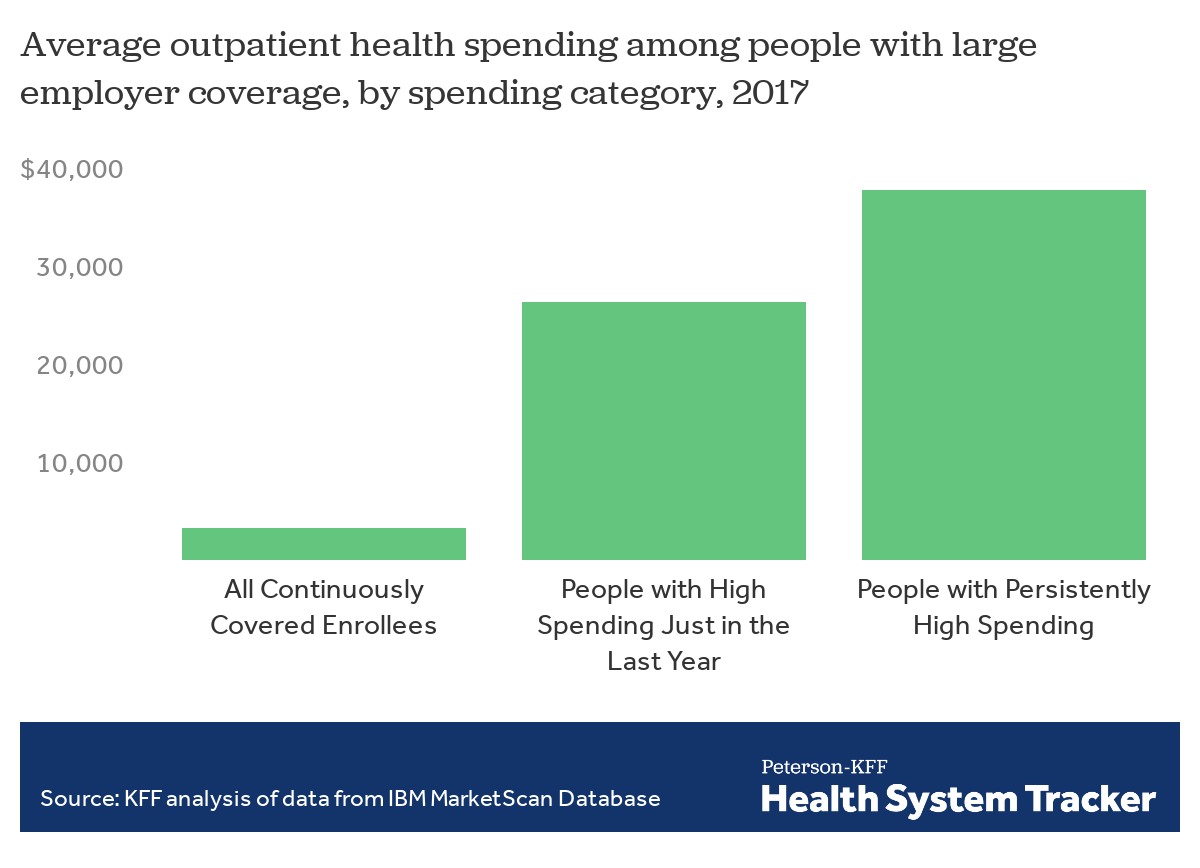

People with persistently high spending on average spent about 40% more on outpatient services than people with high spending just in the last year

People with persistently high spending averaged $37,790 in spending on outpatient services in 2017, 44% more than the average amount for people with high spending just in the last year ($26,290). One reason is that they used more services: those with persistently high spending had an average of 137 outpatient claims in 2017, compared with 106 for people with high spending just in the last year. The overall average among continuously covered enrollees was 25 outpatient claims per enrollee in 2017.

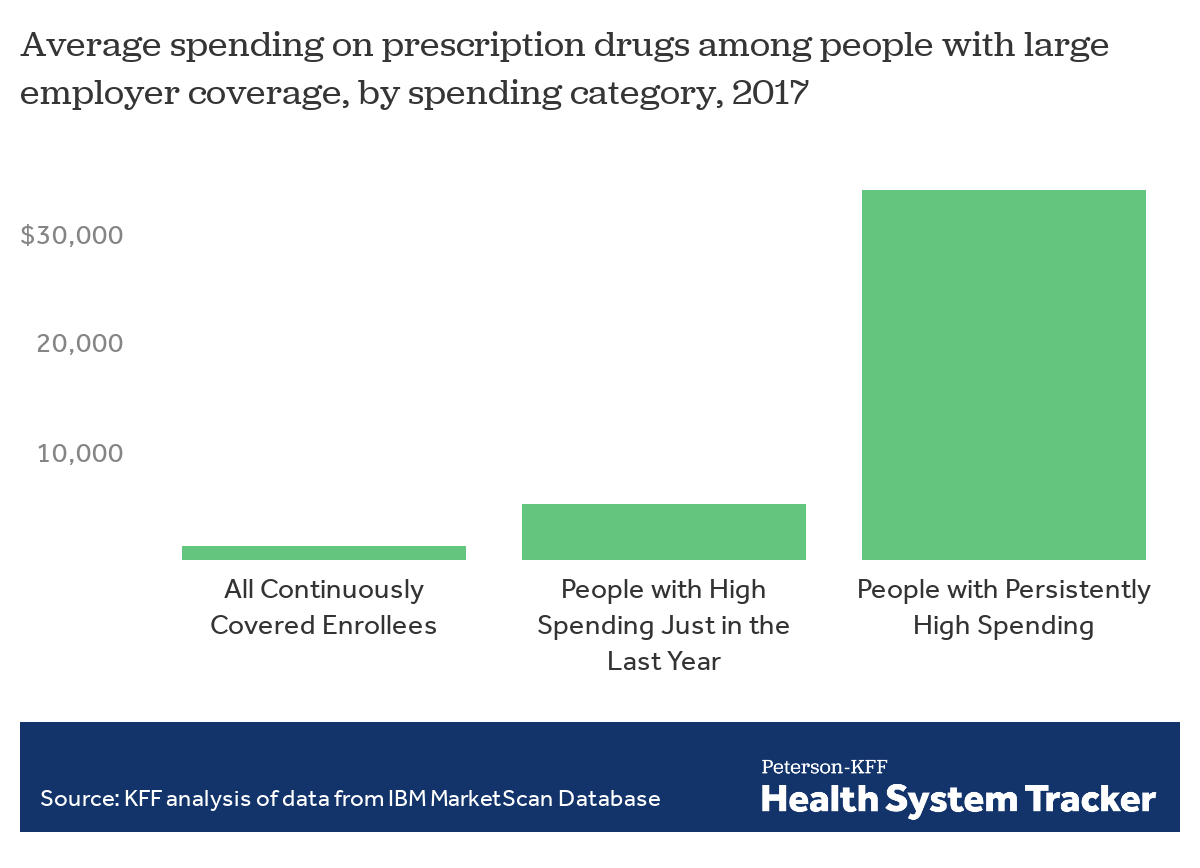

People with persistently high spending also had much higher spending on retail prescription drugs

People with persistently high spending averaged almost $34,000 in spending on retail prescription drugs (not reflecting any rebates manufacturers may have paid), many times more than the average for people with high spending just in the last year or continuously covered enrollees overall. While this average amount was affected somewhat by a small share of enrollees with very high prescription spending, the median prescription spending for those with persistently high spending was about $23,000, demonstrating the pervasiveness of high prescription spending among this group.

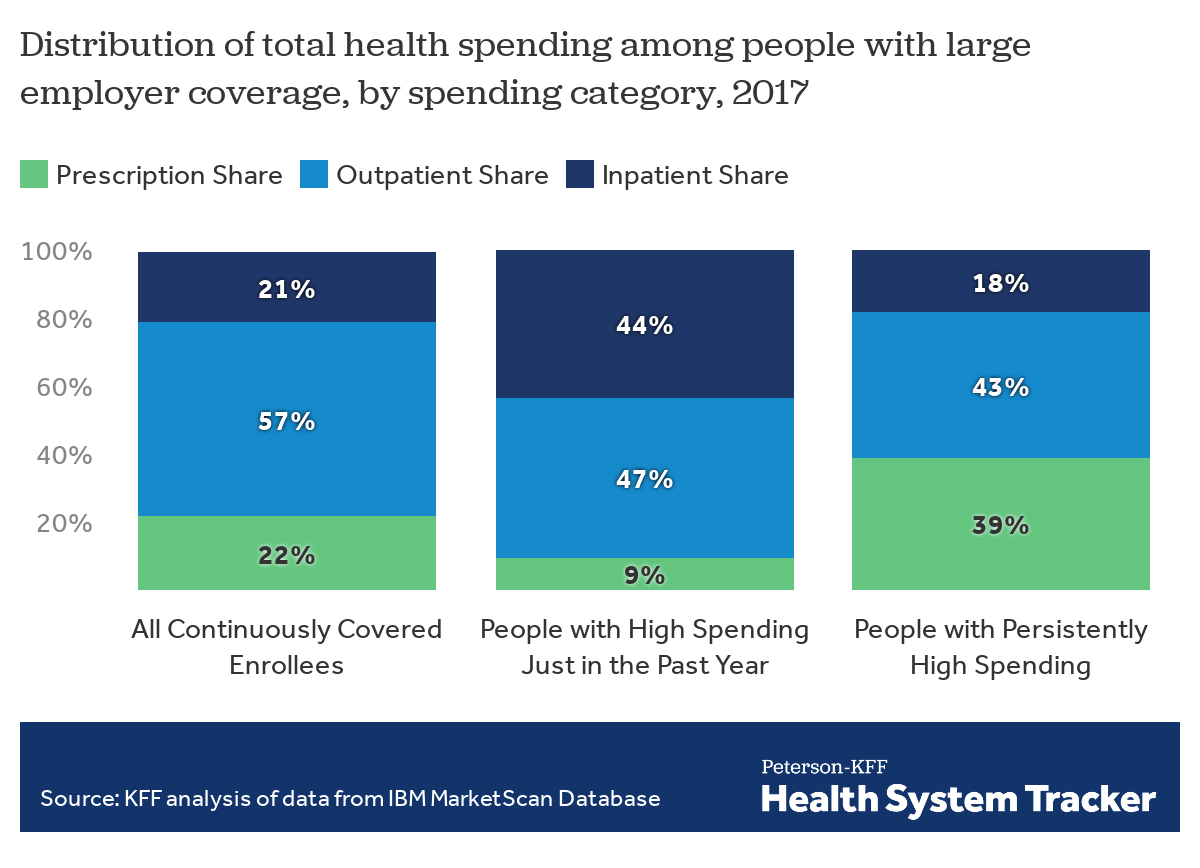

Spending on prescriptions was a significant share of the total spending by people with persistently high spending

Spending on retail prescriptions comprised 39% of total spending by people with persistently high spending, a considerably higher share than for people with high spending just in the last year (9%) or for continuously covered enrollees overall (22%). This pattern, and the high amounts spent on prescriptions shown in the previous slide, show the importance of prescription medicines in treating people with chronic health conditions and ongoing care needs. While manufacturer rebates, which are not publicly known, would reduce this amount somewhat, there is no doubt that prescription drugs represent a disproportionate expense for those with persistently high spending.

In contrast, people with high spending just in the last year had a much higher share of their spending for inpatient services (44%) than those with persistently high spending (18%) or continuously covered enrollees overall (21%).

Who has persistently high spending?

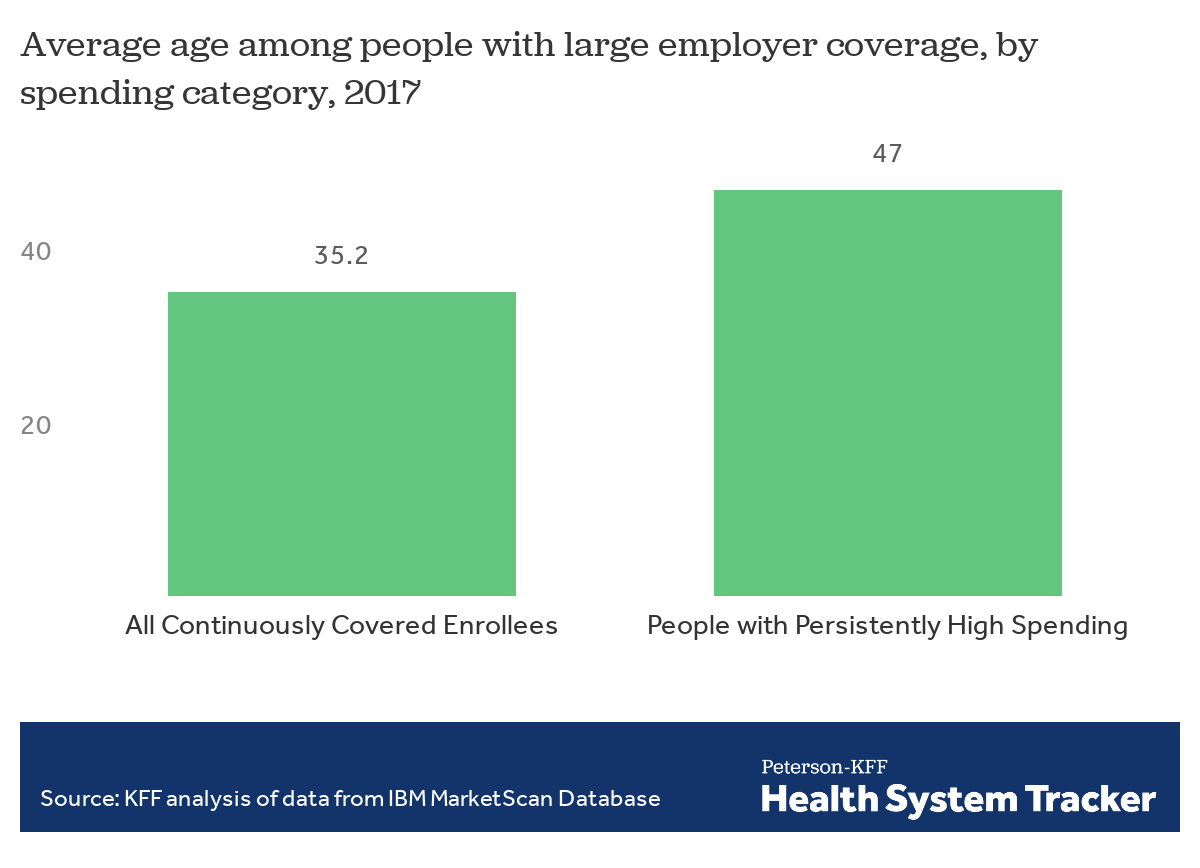

People with persistently high spending are older on average

People with persistently high spending were over a decade older, on average, than continuously covered enrollees overall. While people of all ages have chronic illnesses, they are more prevalent at older ages. Only 7% of people with persistently high spending were under age 19, as compared to about a quarter of continuously covered enrollees.

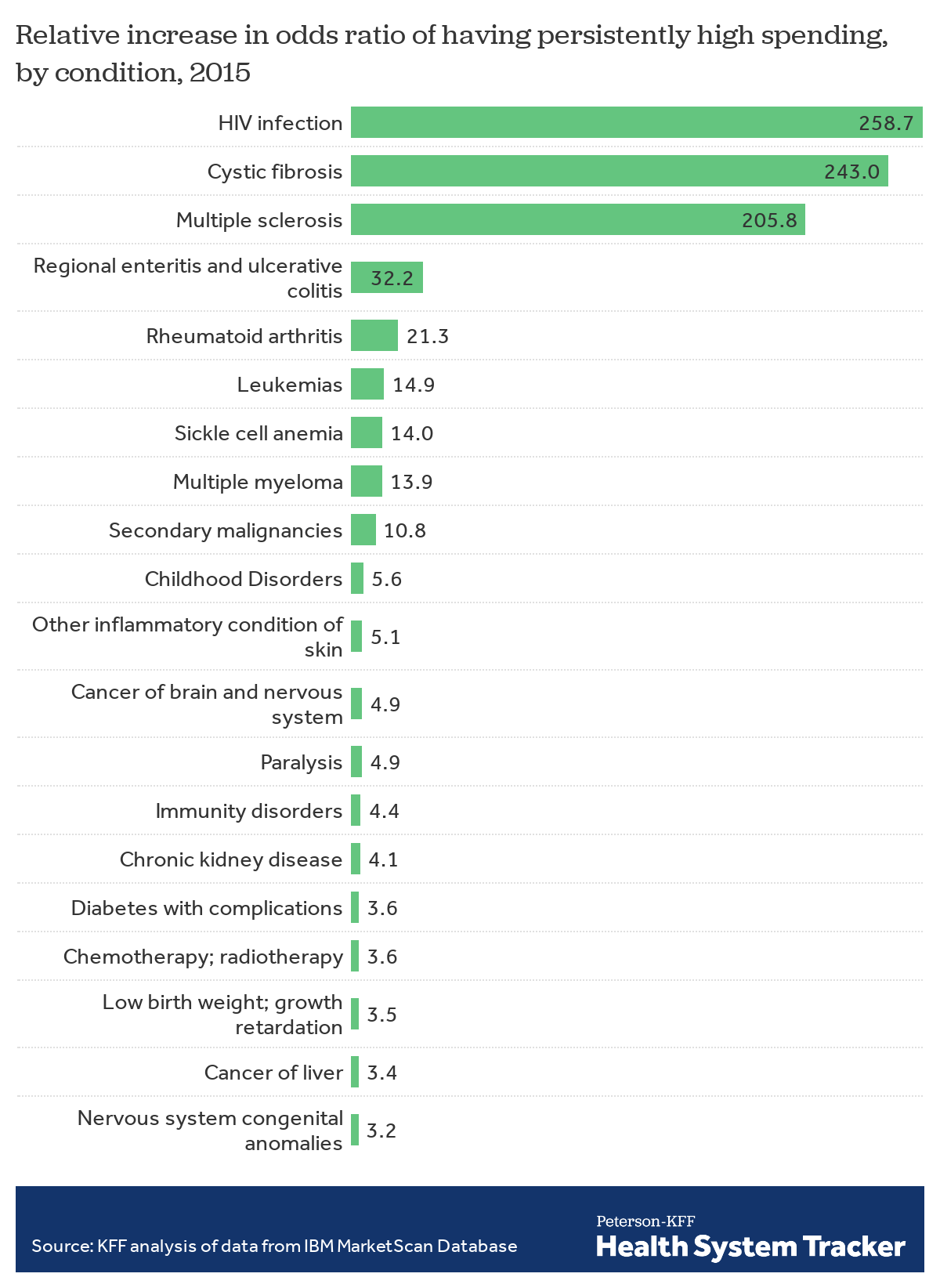

Having certain health conditions increases the chances of having persistently high spending

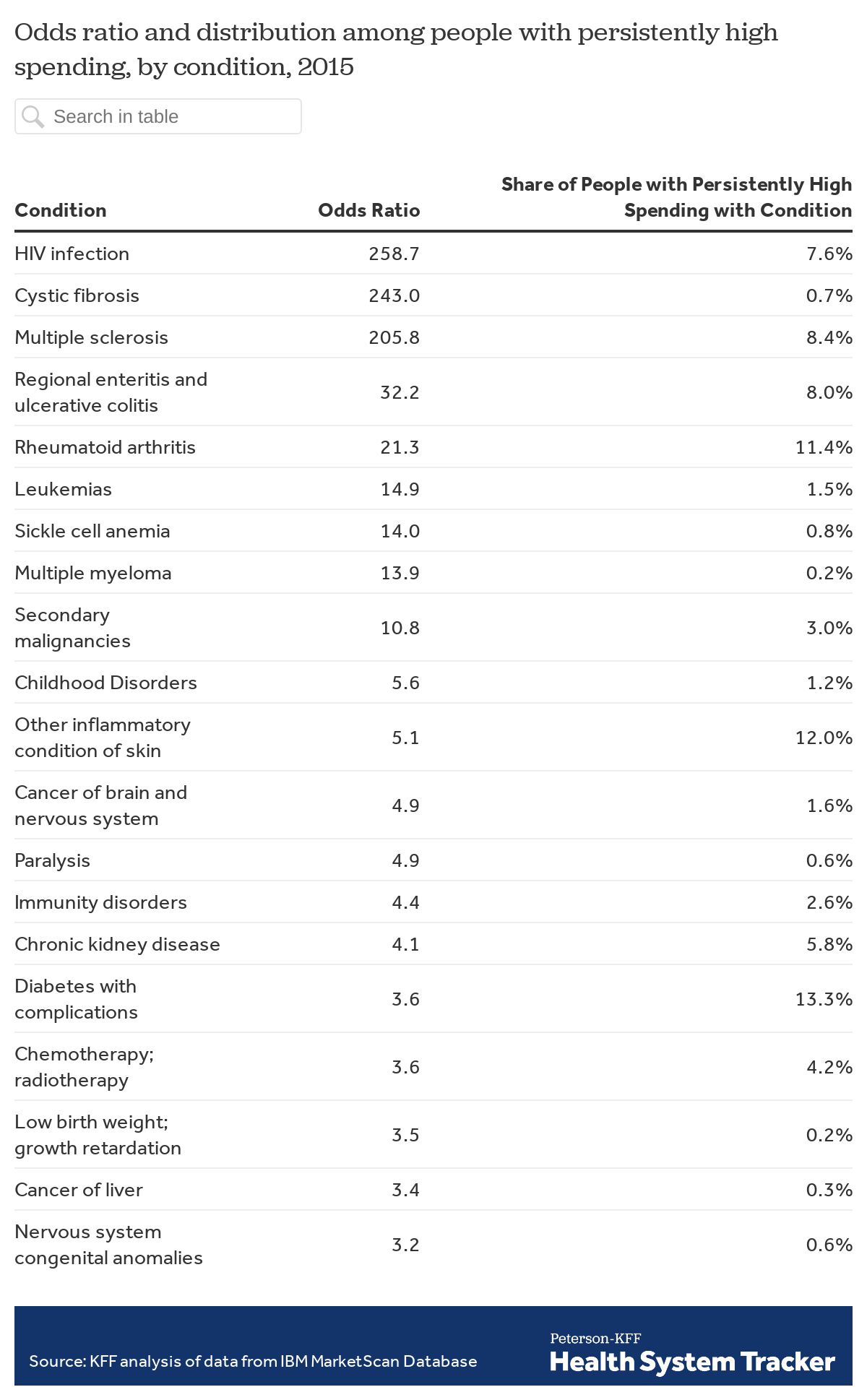

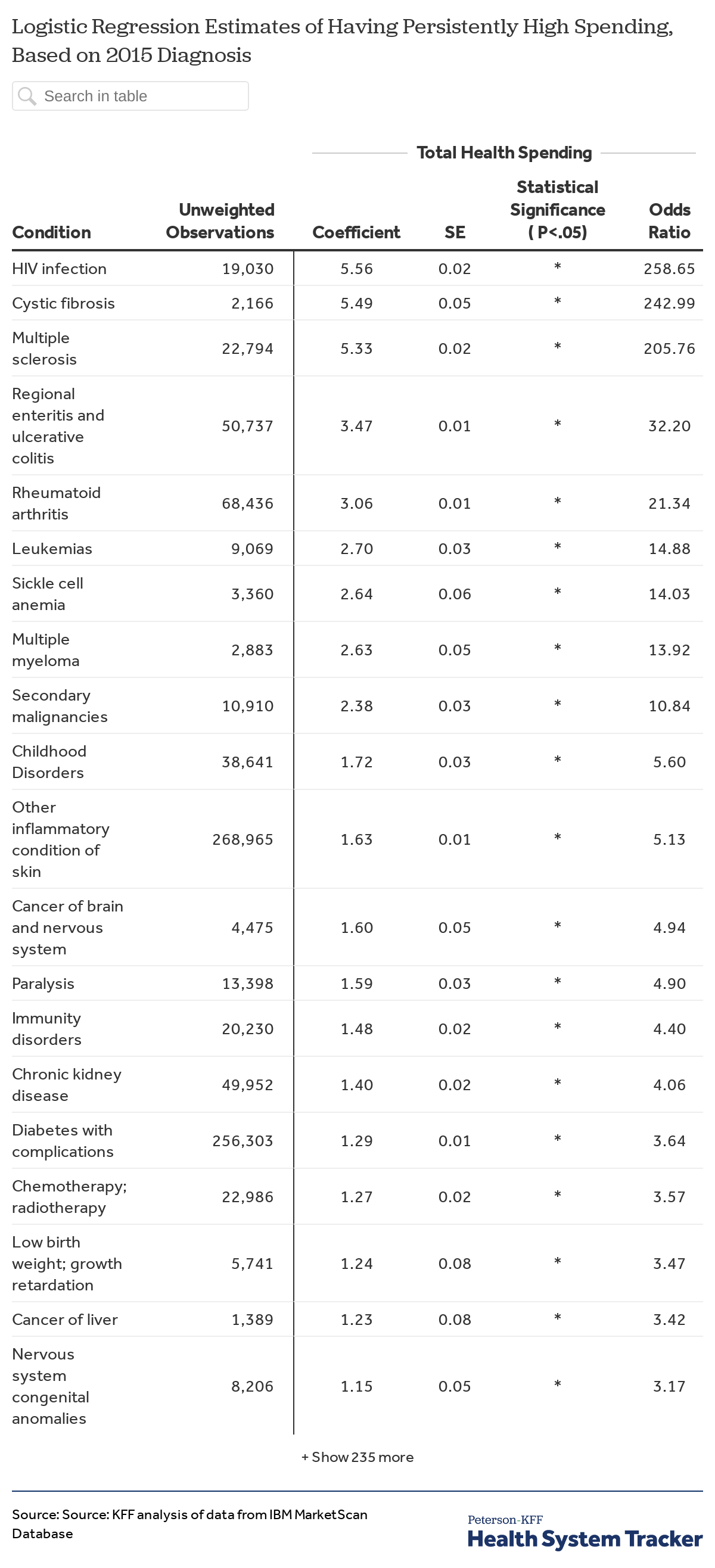

We developed a logistic regression model to analyze the association between the health conditions continuously covered enrollees had in 2015 and having persistently high spending. All continuously covered enrollees were assigned to one or more of 283 distinct diagnostic categories based on the primary (first) diagnoses for any outpatient event or principal diagnosis for any inpatient admission. The chart shows the results for the conditions with the 20 highest odds ratios; the full results and an alternative specification are presented in Appendix.

The results show the increase in the odds that someone with each specified health condition in 2015 had persistently high spending as compared to the odds for someone who did not have the condition. The odds can be thought of as the probability of having persistently high spending divided by the probability of not having it. For example, the odds of having persistently high spending were about 259 times higher for a person with HIV as compared to a person without HIV, all else being equal. Cystic fibrosis and multiple sclerosis increased the odds of having persistently high spending 243 times and 206 times respectively. While these three conditions had the biggest impacts on the odds, having any of several other illnesses or conditions, such as regional enteritis and ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, leukemia and multiple myeloma, also greatly increased the odds of having persistently high spending.

Almost 70% of people with persistently high spending have one or more of these diagnoses in 2015

Looking at the same 20 illnesses and conditions from the chart above, 69% of people with persistently high spending had one or more of these conditions in 2015, compared with just 6% of continuously covered enrollees overall. About 11% of those with persistently high spending had rheumatoid arthritis in 2015, 8% had HIV, and 13% had diabetes with complications. (Note the column sums to more than 69% percent because some people with persistently high spending had multiple conditions and were counted in more than one category).

That such a large share of people with persistently high spending fell into such a narrow range of disease categories helps us better understand who they are. Given their ongoing high health care need, identifying people with these (and similar) diagnoses early in their treatment and assessing the appropriateness and cost-effectiveness of their courses of care is clearly important to any efforts to improve value and lower overall spending.

Large shares of people with certain diagnoses in 2015 developed persistently high spending

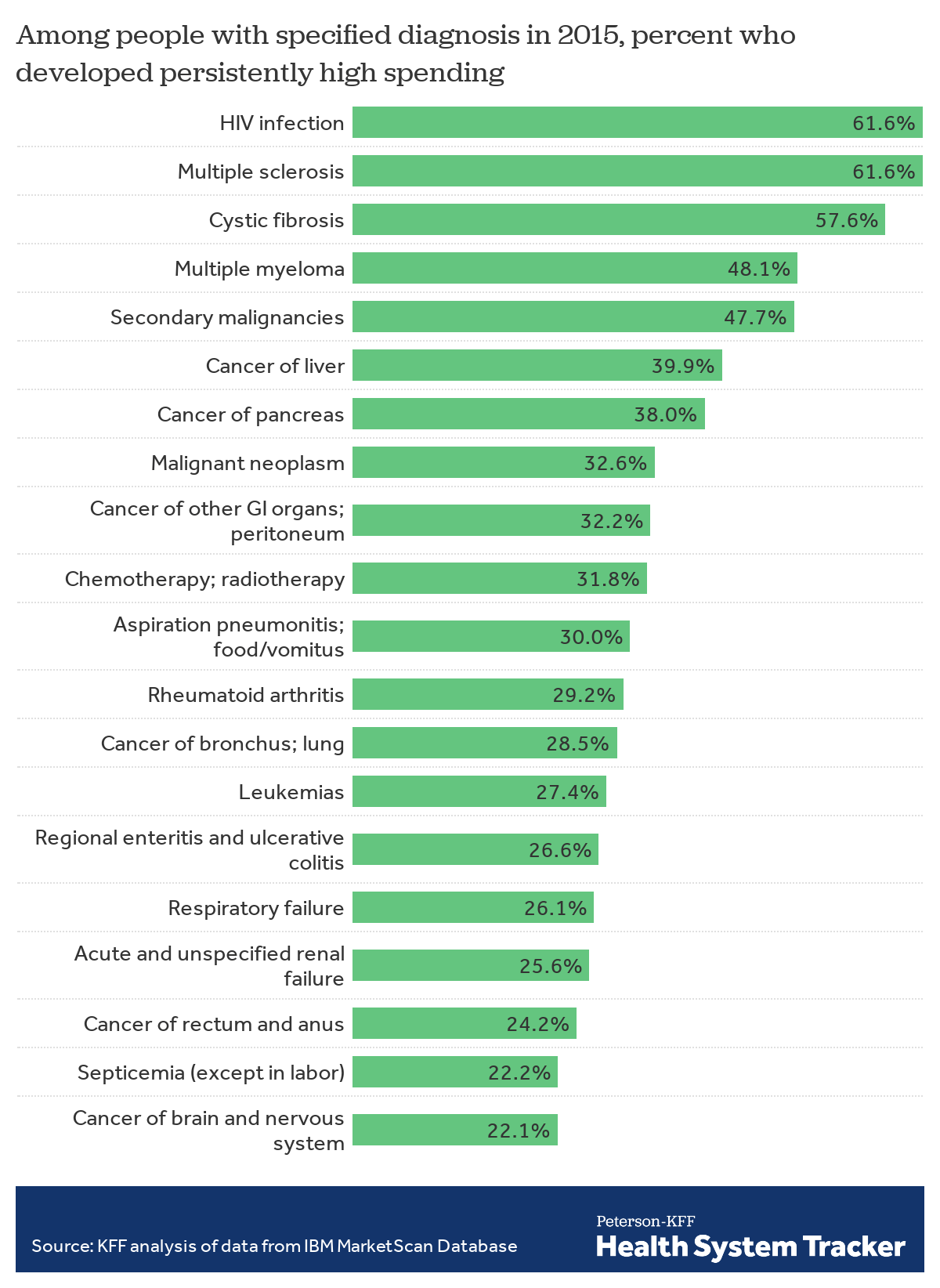

Another way to look at who has persistently high spending is to focus on the share of people in each illness or condition category in 2015 who developed persistently high spending. This figure shows the 20 illnesses and condition categories with the highest share of people with persistently high spending among those diagnosed with the condition in 2015. For example, more than 60% of continuously enrolled individuals with HIV or multiple sclerosis in 2015 had persistently high spending.

One thing that stands out is the number of cancer diagnoses with a high share of people with persistently high spending. While many of these conditions are fairly rare, and most people with each of these diagnosis in 2015 do not develop persistently high spending, a quarter or more do so in each of the categories.

Discussion

Health spending is highly concentrated: a small share of people account for most health care in a year. This group changes from year to year as some people experience serious illness and recover, but a share of the group continues to have high spending for longer periods. We followed a subset of people with employer-based coverage who were continuously insured over a three-year period (2015-2017) and identified a group of people with persistently high spending whose health spending was in the top five percent in each of the three years. Overall, these people with persistently high spending comprised only 1.3% of the continuously covered subgroup but accounted for 19.5% of total spending in the final year of the period (2017). Their extensive health care need and predictably high spending make them an important focus for any efforts to improve value and quality.

While those with persistently high spending had a variety of health conditions, a large proportion had claims in the first year that for a narrow set of diagnoses, including HIV, multiple sclerosis, cystic fibrosis, rheumatoid arthritis, as well as a number of cancers. While not everyone with these conditions has persistently high spending, knowing that there are large shares with persistently high spending within these disease groups helps us better understand where some of the most significant health needs and costs are concentrated.

Compared to people with high spending just in the last year, people with persistently high spending had higher spending for prescription drugs and lower spending for inpatient services. This underscores the importance of prescription drugs in treating people with chronic illnesses as well as the fact that some of these drugs are quite costly. This is both an opportunity and a challenge. There is bipartisan support to lower prescription drug costs, including some of the very expensive drugs that may be used to treat people with complex or relatively rare diseases. At the same time, medications underpin treatment for many people with chronic illnesses, and new medicines are often the best hope for future improvements in care, and, in some cases, lowering treatment spending overall. Balancing the legitimate concern about costs with the need to encourage research and dissemination of new drug therapies is among the most important challenges facing health policy today.

Methods

We analyzed a sample of medical claims obtained from the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database (MarketScan), which contains diagnostic and claims information provided by large employer plans for several million employees and their dependents. MarketScan allows for enrollees to be tracked for their duration at one contributing employer, and we used a subset of claims for enrollees covered in each of three years, 2015 through 2017. We only included claims for people under the age of 65. Our unweighted subset contains 12,668,720 of these continuously covered enrollees, including 169,315 “people with persistently high spending” and 324,742 “people with high spending just in the last year.” People with persistently high spending had total claims spending in excess of the 95th percentile of total claims spending in each of the three years. People with high spending just in the last year had claims spending in excess of the 95th percentile of total claims spending in 2017 but not in 2015 or 2016.

The MarketScan database is a convenience sample and may not accurately represent the population of people with health benefits through large employers. To limit the impact of this bias, weights were applied to match counts from the Current Population Survey for enrollees at firms of a thousand or more by sex, age, state and whether the enrollee was a policyholder or dependent. Weights were trimmed at 8 times the interquartile range. This sample represented about 14% of the 86 million people in the large group market.

Claims data available in MarketScan allows an analysis of liabilities incurred by enrollees with some limitations. First, claims data show the retail cost for prescription drugs and do not include information about the value of rebates that may be received by payers. Rebates vary significantly by drug. Secondly, these data reflect cost sharing incurred under the benefit plan and do not include balance-billing payments that beneficiaries may make to health care providers for out-of-network services or out-of-pocket payments for non-covered services.

ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis codes were used to classify 283 distinct illness and conditions. Disease classification are based on whether an enrollee received at least one primary diagnoses for any outpatient event or principal diagnosis for any inpatient admission at any point in 2015. We used the disease definitions developed by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). We modeled the association between conditions and illness and whether someone had persistently high spending using the “binominal” parameter of the glm function in R 3.6. This method applied a logistic regression, estimating the odds that a diagnosed person had persistently higher spending. We used a person’s diagnosis in 2015 for a separate model for each of the 283 conditions holding constant an enrollees’ state of residency, sex, age and whether they were the policyholder or a dependent. Conditions with fewer than 1,000 observations were excluded from the results.

Because many chronic conditions are treated with expensive drug regimens, we were concerned that not being able to account for rebates would exaggerate the effect of conditions with high drug costs and high rebate levels. Prescription drug rebates vary considerably across particular drugs and drug categories, which can affect the costs associated with the diagnoses those drugs are used to treat. To test the robustness of our coefficients, we applied a 25% reduction to all drug spending and re-specified the model. This reduction had a greater impact on enrollees with a higher share of drug spending. Both the original specification and alternate described here are available below.

All dollar values are reported in 2017 nominal dollars.

Appendix

The Peterson Center on Healthcare and KFF are partnering to monitor how well the U.S. healthcare system is performing in terms of quality and cost.