Medical debt can be a significant financial burden on people and families. Having medical debt can exhaust savings, force families to delay or forgo basic necessities, and divert resources from other important family needs such as housing, education, and retirement. KFF polling has found people in families with medical debt are also much more likely to delay or forgo medical or dental care than people without medical debt.

Medical debt is just one component of a person’s overall financial situation. The National Financial Capabilities Survey (NFCS) is a triennial survey sponsored by the FINRA Foundation that provides information on the financial security, experiences, and vulnerabilities of people and households.

People with medical debt are much more likely to have other forms of financial distress than those without medical debt. Key findings include:

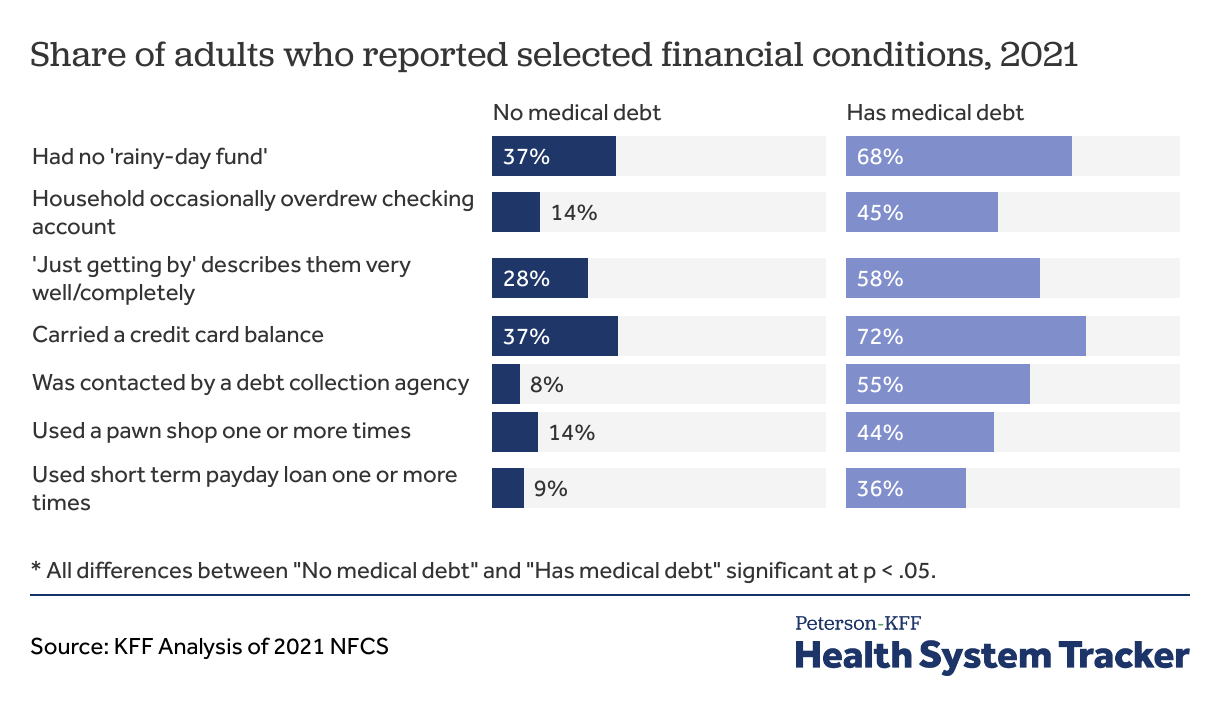

- Indicators of financial vulnerability — such as spending more money than one’s income, having no “rainy day” fund, or agreeing with the statement “I am just getting by financially” — are more common among adults with medical debt than those without.

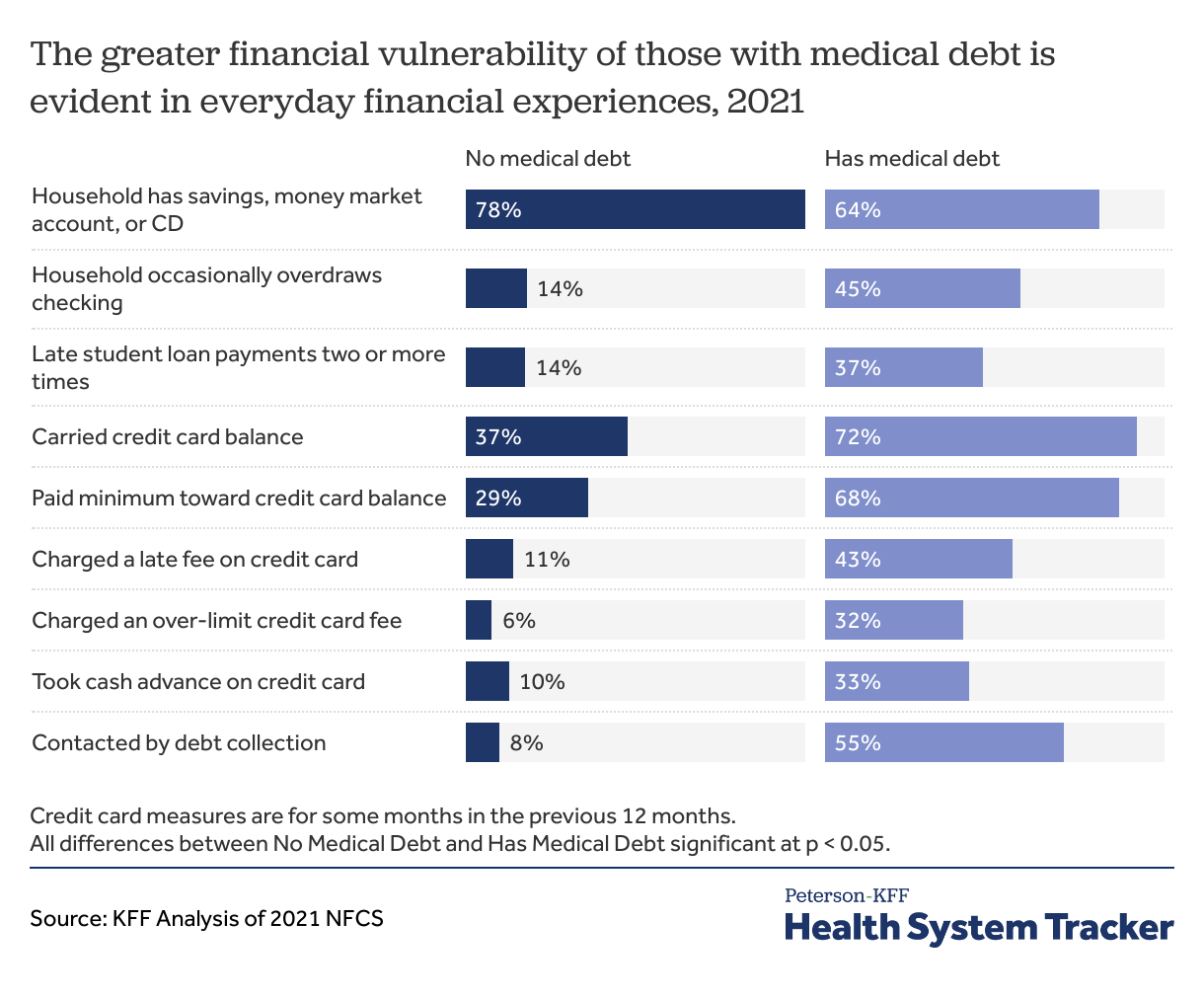

- Additionally, people with medical debt are more likely to overdraw their checking account, have a credit card balance that exposes them to interest payments, take a cash advance on their credit card, or have been contacted by a debt collection agency.

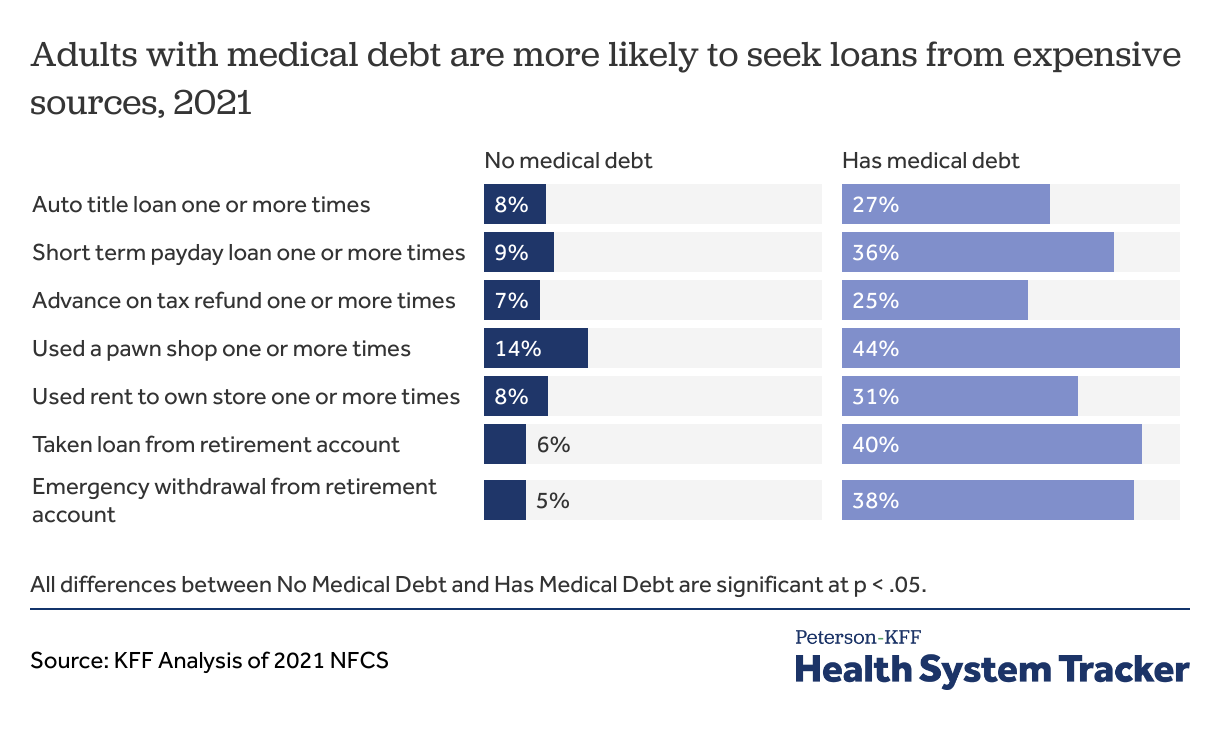

- Adults with medical debt are much more likely to use pay day loans or other costly loans than those without medical debt.

Medical debt is associated with financial vulnerability across a range of indicators

Medical debt is common in the United States. In the 2021 NFCS used in this analysis, 23% of U.S. adults had medical debt, meaning they had one or more unpaid bills from a medical service provider that were past due at the time of the survey. This is similar to the result from the KFF Health Care Debt Survey, which found that 24% of adults had one or more medical or dental bills that were past due or that they were unable to pay. (The KFF survey also found that 41% of adults have health care debt according to a broader definition, which includes health care debt on credit cards or owed to family members.) For more discussion of the similarities and differences across various surveys on medical debt, see the Appendix.

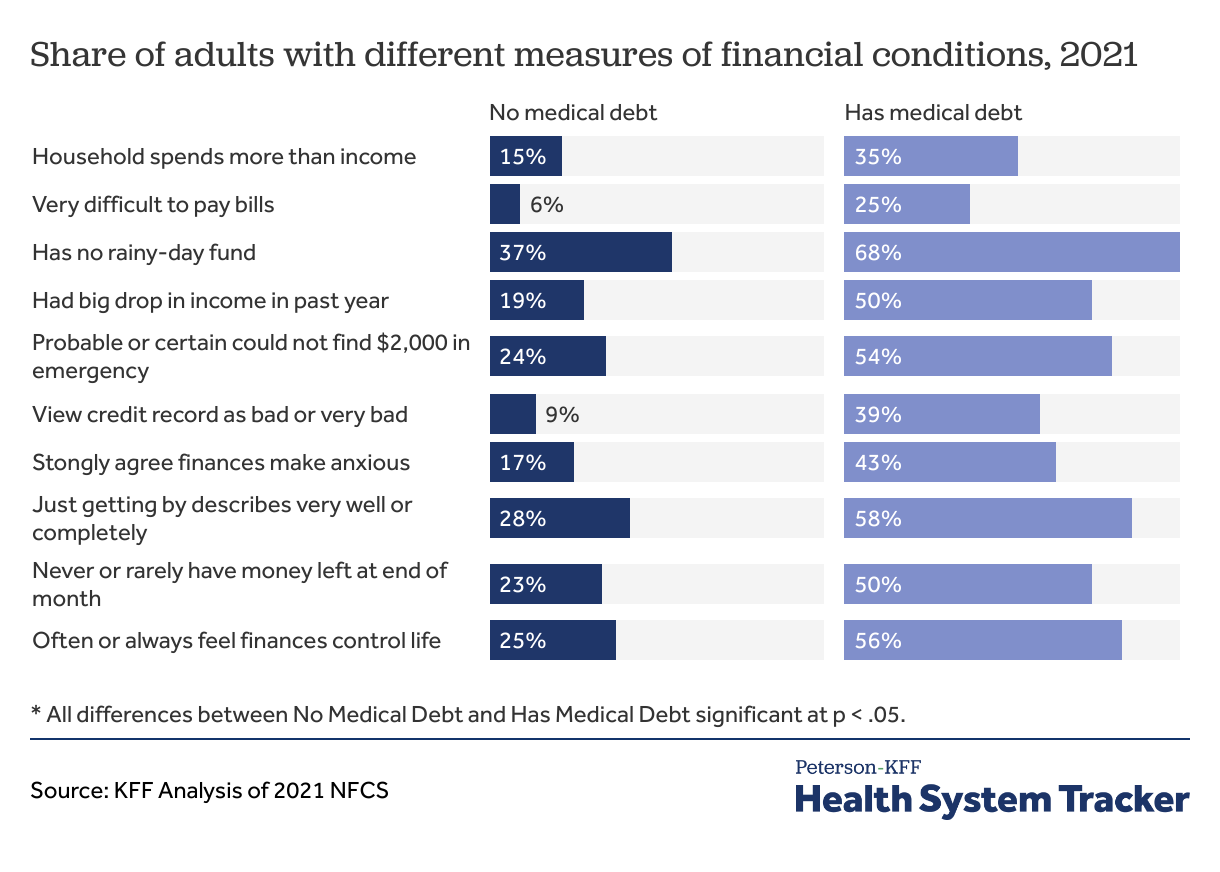

Adults with medical debt are more likely than those without medical debt to show signs of financial vulnerability across a range of financial measures. Adults with medical debt are more likely to be in a household that spends more than its income, find it very difficult to pay their bills, have no “rainy day” fund, or have had a big drop in income in the past year. Adults with medical debt also are more likely to view their credit report as bad or very bad, to say that “just getting by” describes them well or very well, to rarely or never have any money left at the end of the month, or to say that they often or always feel that their finances control their lives.

Although adults without health insurance are more likely to have medical debt, the financial vulnerability shown across these measures persists even when the population of respondents is limited to adults with insurance. A large majority of the population has health insurance, and more than one-in-five adults with health insurance have medical debt. Although medical debt is more concentrated among certain groups – people with low incomes, the uninsured, people unable to work due to their health – it affects people and households across the financial spectrum.

The greater financial vulnerability of those with medical debt is evident in everyday financial experiences

Adults with medical debt are less likely than those without medical debt to have some form of savings account and are more likely to overdraw their checking account or to make late payments on their student loans. They also are more likely, measured for some months over the previous 12 months, to have a credit card balance that exposes them to interest payments, to be charged a late fee or an over-the-limit fee on their credit card, or to take a cash advance on their credit card. More than one half (55%) have been contacted by debt collectors, compared to 8% of adults with no medical debt.

Adults with medical debt are more likely to use payday loans or other costly sources

Adults with medical debt are much more likely than adults without medical debt to seek a payday loan, use a pawn shop, use a rent-to-own store, or seek a loan against the title of car. They also are more likely to take a loan or an emergency withdrawal from a retirement account. These types of transactions often come with relatively high interest rates or penalties and can add additional financial stress to already vulnerable households.

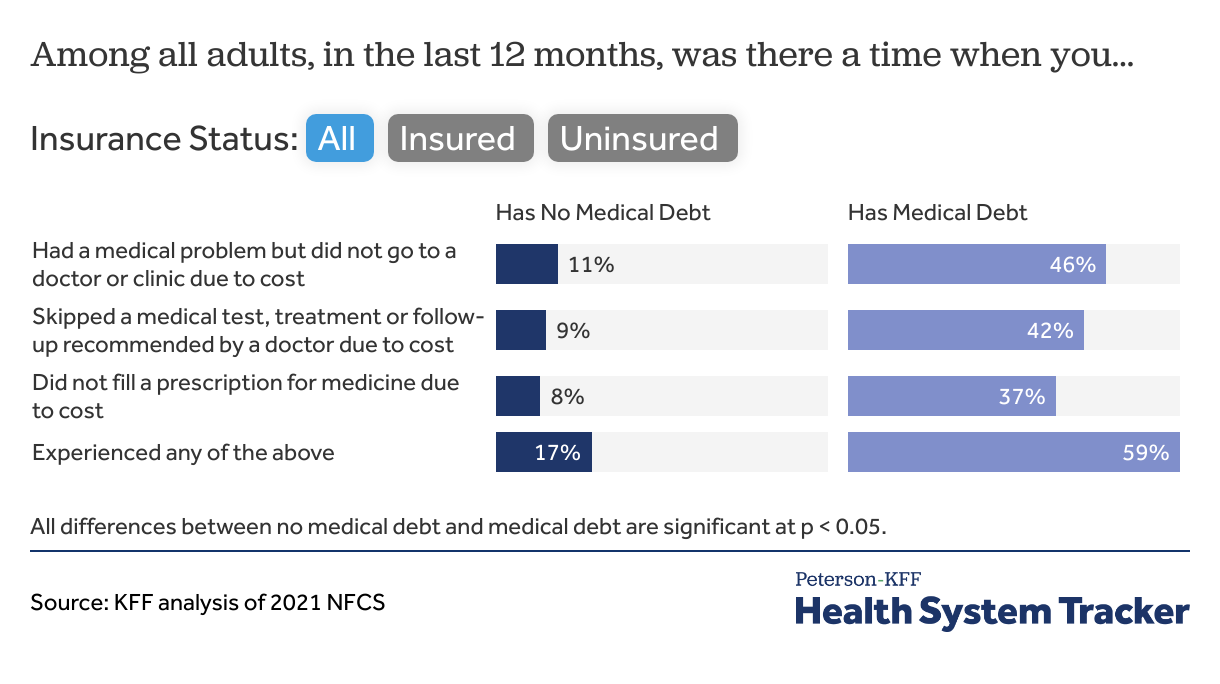

Adults with medical debt are more likely to delay or forgo needed medical care due to cost

Compared to adults with no medical debt, those with medical debt are much more likely to forgo needed medical care; skip a test, treatment, or follow-up care; or not fill a prescription due to cost. These differences persist both among people with insurance and among people without insurance. The overall finding is consistent with the KFF Medical Debt Survey, which showed that large shares of people with medical debt delayed or did not seek out needed medical care.

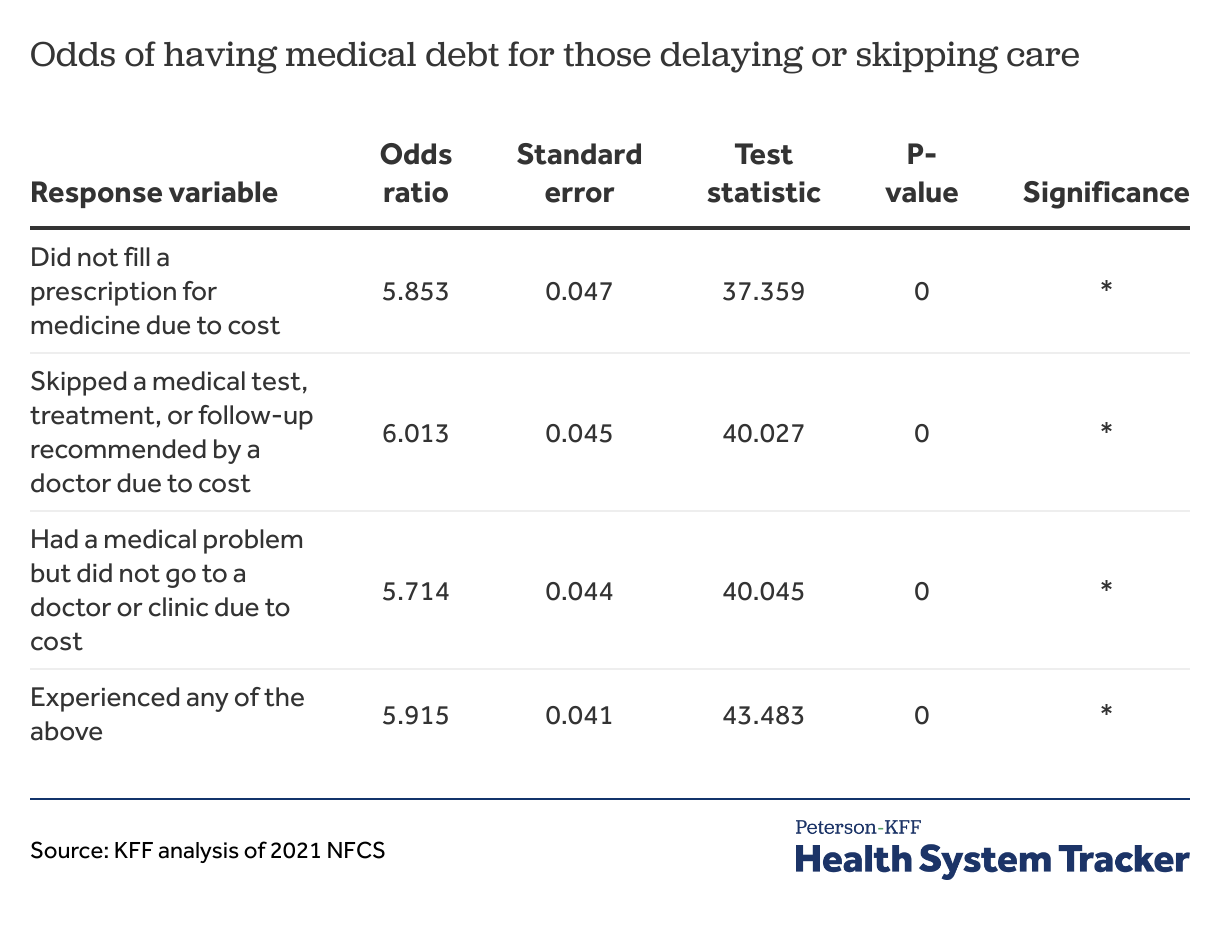

Young, lower-income individuals with medical debt are more likely to report delaying or skipping care. To evaluate how medical debt impacts medical access, we estimated the increased odds that a person skips or delays care when they have medical debt, controlling for age and income level (See Appendix). For example, an adult between the ages of 18 and 24 who reports having medical debt and makes less than $50,000 a year has a 75% chance of experiencing medical affordability problems such as skipping a medical test or treatment, delaying care, or not filling a prescription due to cost. An adult between the ages of 25 and 54 and an adult 55 or older within the same lower income bracket and with medical debt have a 67% chance and 47% chance respectively of reporting these same affordability issues.

Discussion

The prevalence and consequences of medical debt have gained more public attention in recent years. Large shares of households with medical debt are financially vulnerable, identifying with phrases such as “just getting by” or “finances control my life.” These results persist when the population is limited to those with insurance, demonstrating that the problem of medical debt is not just, or even primarily, a problem for the uninsured.

Medical debt can stem from various factors, including unaffordable cost-sharing obligations, visits to out-of-network healthcare providers, or the necessity for services not covered by their insurance plan. Medical debt is often just one component of an individual’s overall financial situation, and it frequently compounds other forms of financial instability they may be experiencing. This heightened financial instability can result in individuals forgoing necessary medical care due to concerns about the affordability of services.

Appendix: What are the differences in various surveys on medical debt?

Questions about medical debt and other financial matters can be difficult to compare across surveys. For example, it is not always clear whether respondents are answering about their personal experiences or about their broader family or household. Surveys typically ask about different reference periods, or the amount of time which they want respondents to consider.

The NFCS survey used in this analysis obtains information from over 27,000 adults, which can be used to assess the security and vulnerabilities of household finances, as well as the confidence or insecurity of U.S. adults. The 2021 NFCS was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and so reflects some of the financial concerns that accompanied it. On broad financial measures, however, such as the share of people finding it not at all difficult to pay their bills, the share satisfied with their personal financial situation, the share of people in households spending less than their incomes, the 2021 NFCS showed the same or higher levels when compared to the previous NFCS surveys. This stability offers some confidence that the 2021 NFCS findings provide useful information about the financial circumstances of people with medical debt, outside the financial turmoil during the pandemic. In fact, the share of adults with past due medical bills in the 2021 NFCS is very similar to the share in the 2018 NFCS (23% v. 24%). Another source of information on medical debt, the Survey of Income and Program Participation, shows that 8% of adults, or 15% of households have medical debt.

The KFF Health Care Debt Survey asked respondents to think about money that they currently owe for their own health care or someone else’s, such as a family member or dependent. In contrast, the U.S. Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) asks whether money was owed for a medical bill and not paid in full during the past year for each person over the age of 14 in the sample household. SIPP results, therefore, can be looked at on the individual level or for an overall household. Additionally, the NFCS asked respondents about unpaid bills from a health care or medical service provider (e.g., a hospital, a doctor’s office, or a testing lab) that are past due. The NFCS and SIPP did not specifically mention dental bills in their medical debt question, while the KFF Health Care Debt Survey did. Without prompting, some households may not include past due dental bills in their reported medical debt. A further complexity is what respondents classify as debt; some surveys such as the KFF Health Care Debt Survey, prime respondents to think about a wide variety of financial vehicles, including bills from providers, outstanding credit card balances and borrowing from a friend or relative.

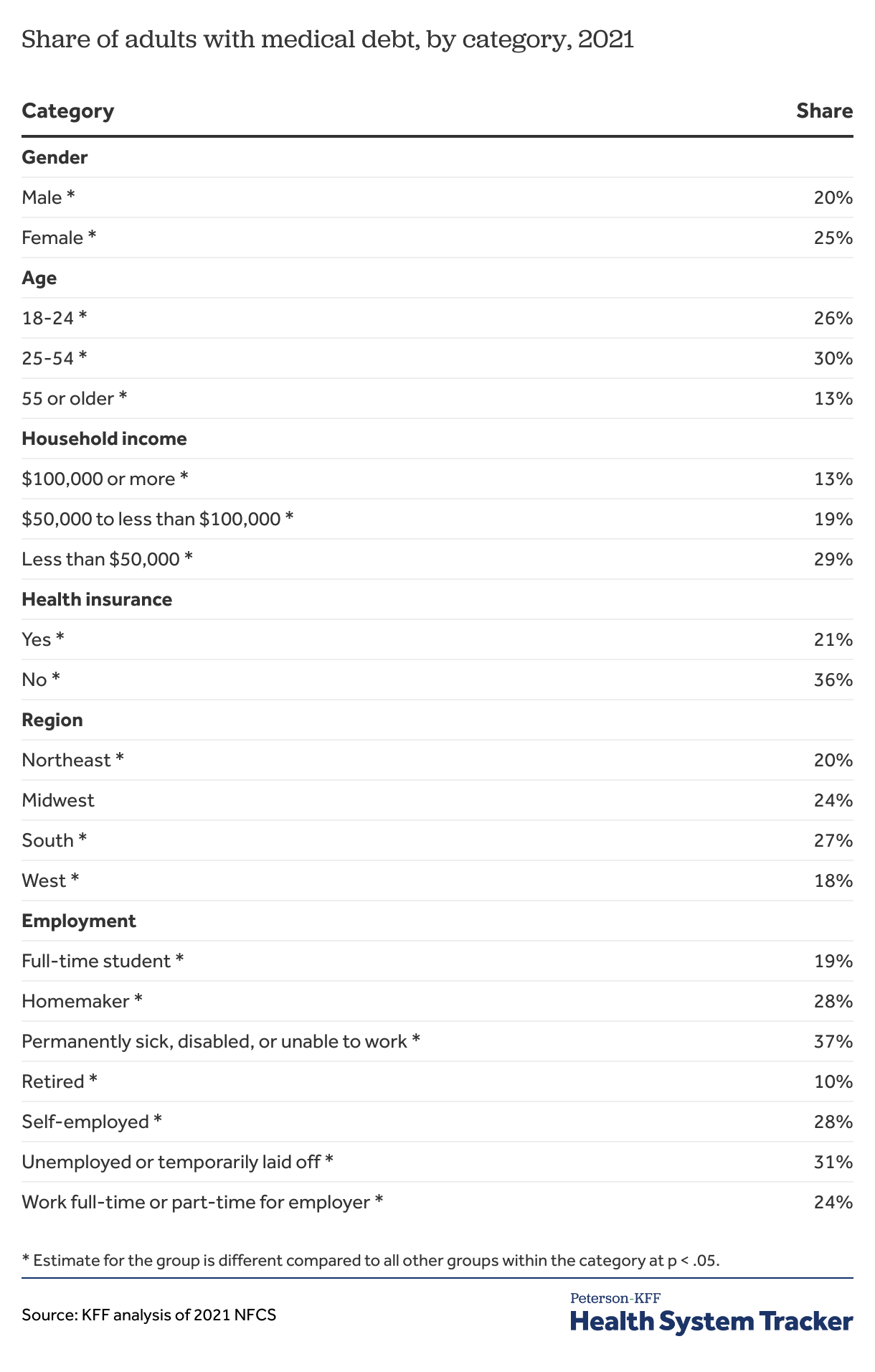

Appendix: The likelihood of having medical debt varies with income, health insurance status and other characteristics

Medical debt is more common for some types of people: women were more likely to report medical debt than men; younger adults (ages 18 to 24) and older adults (55 and older) were less likely to report medical debt than adults aged 25 to 54; adults without health insurance were more likely to report medical debt than adults with insurance, and adults in the South or the Midwest were more likely to report medical debt than those in other regions. Not surprisingly, the incidence of medical debt falls as household income rises. Adults who are sick, disabled, or unable to work have the highest incidence of medical debt, while retirees often have the lowest.

An important caveat when viewing demographic characteristics about medical debt in the NFCS and similar surveys is that they often represent the characteristics of the person being surveyed, and that person is not necessarily the person whose medical care led to the debt being reported. An adult may be reporting debt for care of a child and more than one household member may contribute to the total debt being reported.

Methods

The 2021 National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) consists of a sample of 27,118 adults (above 18 years of age), with approximately 500 respondents in each state and the District of Columbia. California and Oregon were oversampled with 1,250 respondents per state. Respondents were selected using non-probability quota sampling from online panels of millions of individuals provided by Dynata and EMI Online Research Solutions. The survey was distributed through a website format and was self-administered by respondents. The national figures utilized in this analysis were weighted to be representative of the national population based on age, gender, ethnicity, education, and Census division. For more information about survey methods, consult NFCS methodology documentation.

Four logistic regression models were implemented, with each having a different response variable representing some aspect of skipping or delaying medical care. These models used age, income, and the presence of medical debt as predictors. The odds ratios for medical debt were calculated by taking the exponential of the log-odds coefficients generated by the models. Then, 1 is subtracted from these values in order to interpret the odds relative to someone without medical debt. Assuming age and income are fixed, someone with medical debt has 485% higher odds of not filling a prescription for medicine due to cost compared to someone without medical debt. Someone with medical debt has 501% higher odds of skipping a medical test, treatment, or follow-up recommended by a doctor due to cost compared to someone without medical debt. Someone with medical debt has 471% higher odds of having a medical problem but not going to a doctor or clinic due to cost compared to someone without medical debt. Someone with medical debt has 492% higher odds of having at least one of these medical access problems compared to someone without medical debt. These models were also used to predict the probability, or chance, of lower-income individuals with medical debt experiencing any of these medical access or affordability problems.

The Peterson Center on Healthcare and KFF are partnering to monitor how well the U.S. healthcare system is performing in terms of quality and cost.