Collectively, employers are the largest purchaser of health care in the United States, providing benefits for over 153 million people. There is considerable interest in how employers can use their purchasing power to improve quality and reduce cost in the healthcare system. Employer plans typically include plan networks, in which enrollees face lower out-of-pocket expenses if they receive care from a designated provider. By negotiating prices and establishing quality standards with providers participating in the network, employers can attempt to influence the cost and quality of care. Although this may seem like an appealing strategy for employers, particularly large firms with significant buying power, many companies have not used the leverage of network participation aggressively. While networks can mitigate cost growth, there are considerable challenges to developing and promoting these strategies, including concerns that tighter networks may limit enrollee choice and potentially expose employees to out-of-network charges.

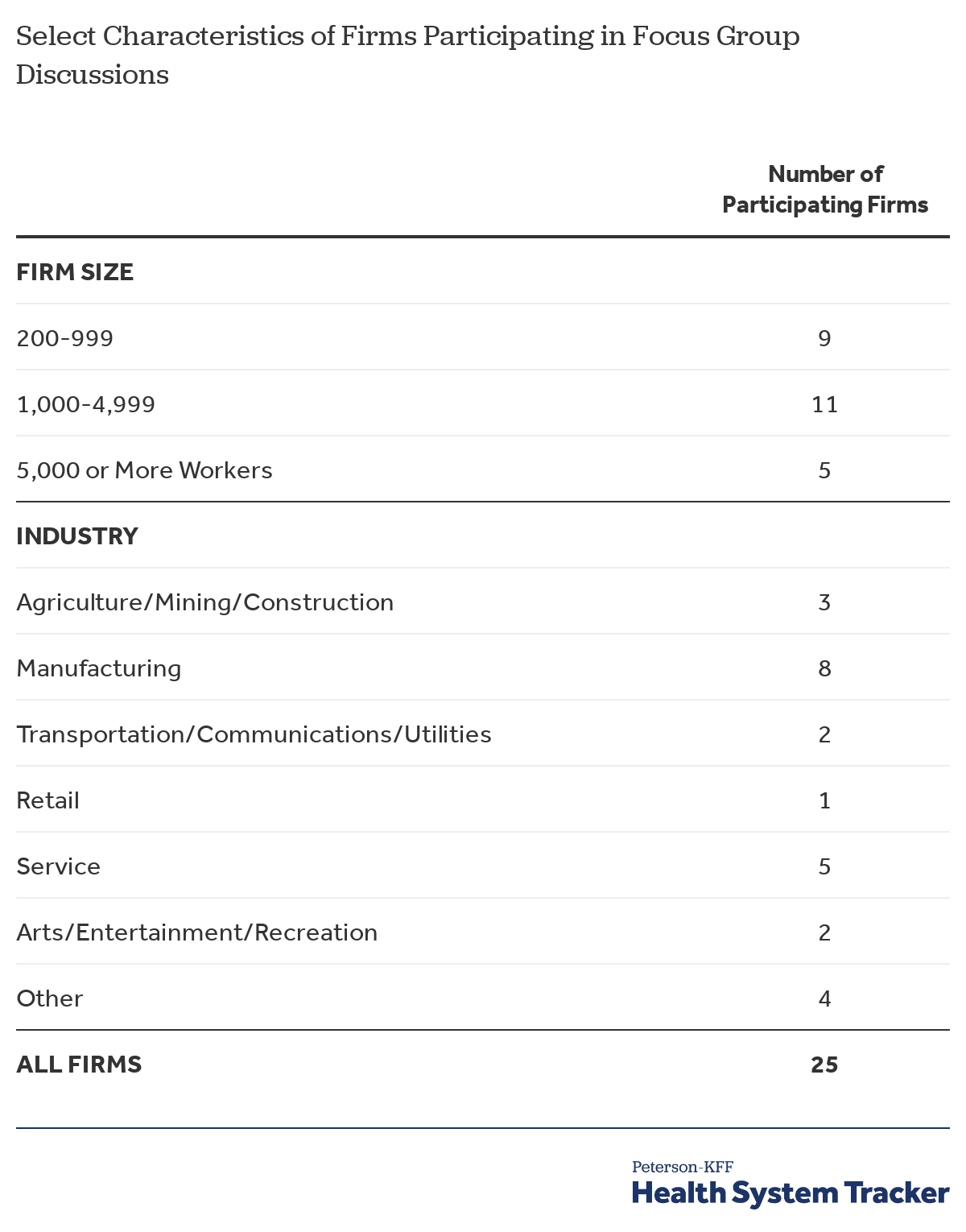

This analysis includes an overview of strategies employers are implementing and offers a deeper understanding of the successes, barriers, and trade-offs firms have experienced in their network decision-making. This report combines data from the Kaiser Family Foundation’s (KFF) 2019 Employer Health Benefits Survey with findings from three focus groups with 25 human resources managers, held in collaboration with the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) and Human Resource Executive (HRE). There remains relatively modest uptake of several strategies to improve costs or quality through provider networks. Barriers to adoption include lack of awareness and information, the geographic distribution of employees, and concern over employee’s potential reaction to changes in provider options.

Strategies in Network Selection

Health plans face trade-offs in developing provider networks. Employees generally value broader networks that give them ample choice of providers and ensure that fewer employees lose their existing providers when transitioning to the plan. At the same time, health plans can ultimately bargain better prices or influence terms of practice only to the extent they are willing to exclude providers from the network. Finding ways to limit their network to more efficient and better quality providers, or to direct employees to choose those providers from within a broader network, are primary tools to influence cost and quality. Health plans attempt to balance designing narrow enough networks that they can bargain with providers about the terms of participation, but broad enough that employers and employees are content with their choices.

Tiered Networks

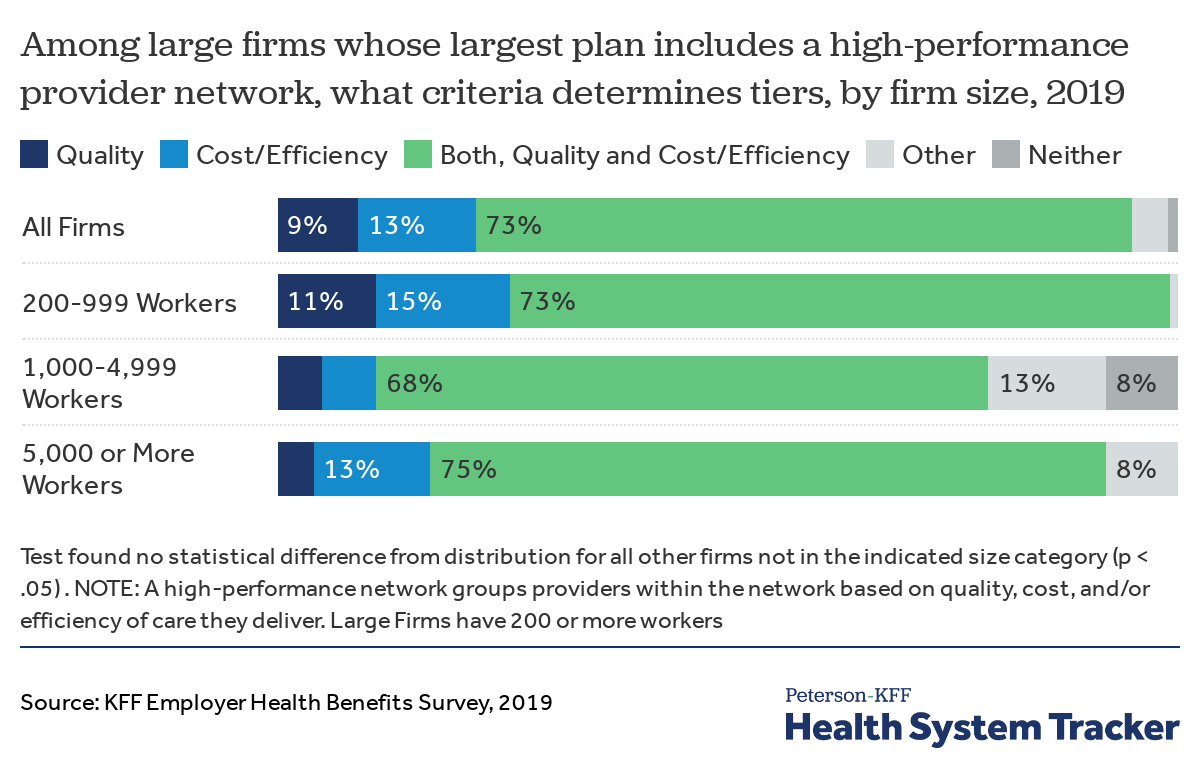

One way that plans have sought to balance the competing desires for broader networks and the use of more efficient, higher quality providers is by creating tiered networks. In a tiered network, the plan divides the providers in its network into two or more distinct groups, typically based on the cost effectiveness and/or quality of the care they provide. Enrollees that elect to use providers on more-preferred tiers typically face lower cost sharing than enrollees receiving care from less-preferred providers. Tiering may be used for all types of providers, or may be limited to select categories such as hospitals or specialists. Most employers electing to contract with a plan with a tiered network say the selection of providers into tiers is based on both costs and quality.

Most firms using tiered networks say they do so to improve both costs and quality

Our survey finds that only 14% of firms with 50 or more workers say their largest health plan includes a tiered network, but the prevalence increases with firm size (31% of firms with 5,000 or more workers include a tiered network in their largest plan). Since 2010, there has been no change in the percentage of offering firms with 50 or more employers whose largest plan includes a tiered network. Even though tiered networks have been shown to meaningfully reduce costs for health plans and enrollees, providers who operate in concentrated markets or have been identified as “must haves” have significant leverage to resist contracting with carriers or employers looking to tier providers.

Most focus group participants had never considered implementing tiered networks in their health plans, and several had never heard of the concept. However, other participants who had adopted tiered networks appreciated that these plans encourage workers to use efficient providers without making it prohibitively expensive for those looking to avoid changing doctors.

“We are trying to drive better outcomes, to get cost containment, and also to make sure our team members are getting the best care. We figured tiering would steer them towards better providers without making it unaffordable if they wanted to go to a doctor they already had a relationship with. So it’s $40 versus $20 if you go to the premium designated provider.” – Analyst, Large Food Services Firm

Narrow Network Plans

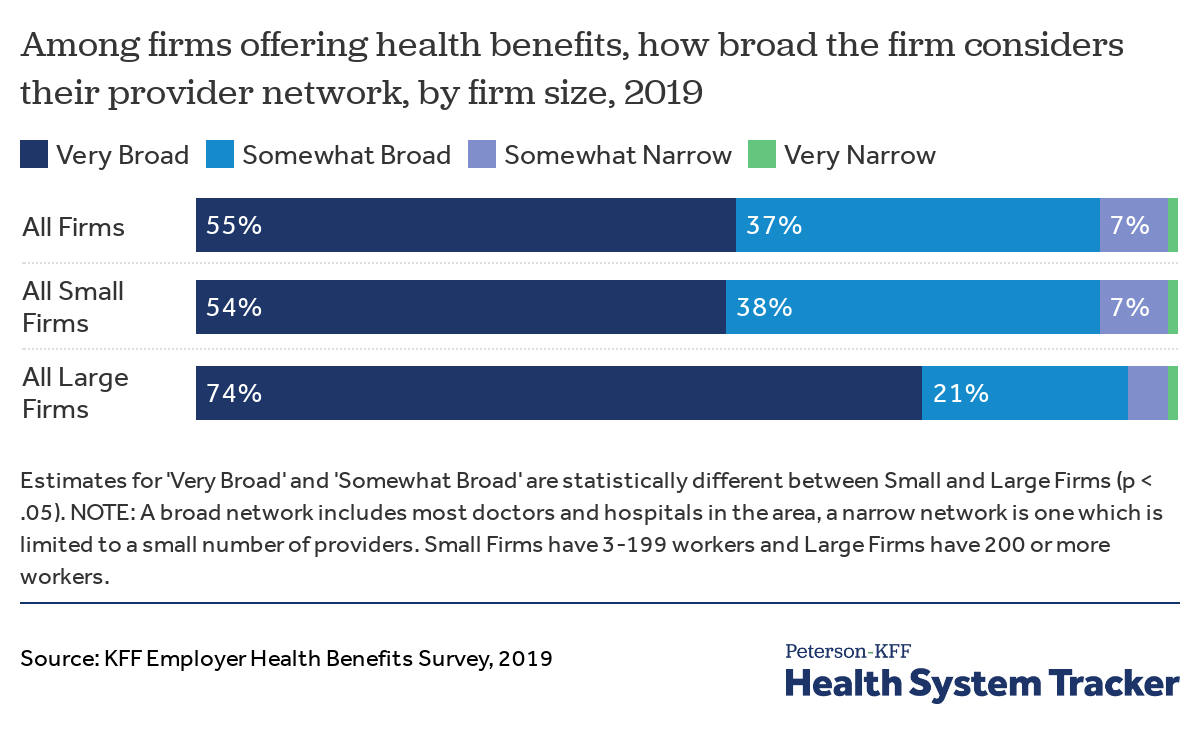

Another, more aggressive strategy that plans use to direct enrollees to more cost-effective providers is to create a network that is restricted only to a limited number of providers that agree to meet relatively stringent cost and/or quality objectives. These plans, often referred to as narrow network plans, have been found to significantly lower premiums and overall spending without necessarily harming access to care, even though fewer providers are covered. Narrow network plans are relatively common in the non-group market but have had limited adoption among employers, with only 5% of employers offering a narrow network plan in 2019.

Less than 1 in 10 employers say their provider network is narrow

Similarly, only 7% of firms categorized the provider network in their largest plan as “Somewhat Narrow,” and less than 1% said their network was “Very Narrow.”

None of the firms participating in the focus groups offered a narrow network plan, but some indicated an interest in doing so in the future. Participants who stated they were considering offering narrow network plans expressed a desire to offer their employees a choice between a skinnier network at a lower cost or a broader, more extensive network at a higher cost. One issue raised by participants, however, is that insurance carriers did not necessarily offer narrow networks in all of the geographic areas where they had employees (this is discussed more below, in the section on barriers).

“We’d like to offer a narrow network within the next few years once our carrier has expanded to more areas. We might offer one narrow network plan and one broader plan for those willing to go narrow.” – Analyst, Large Food Services Firm

Centers of Excellence

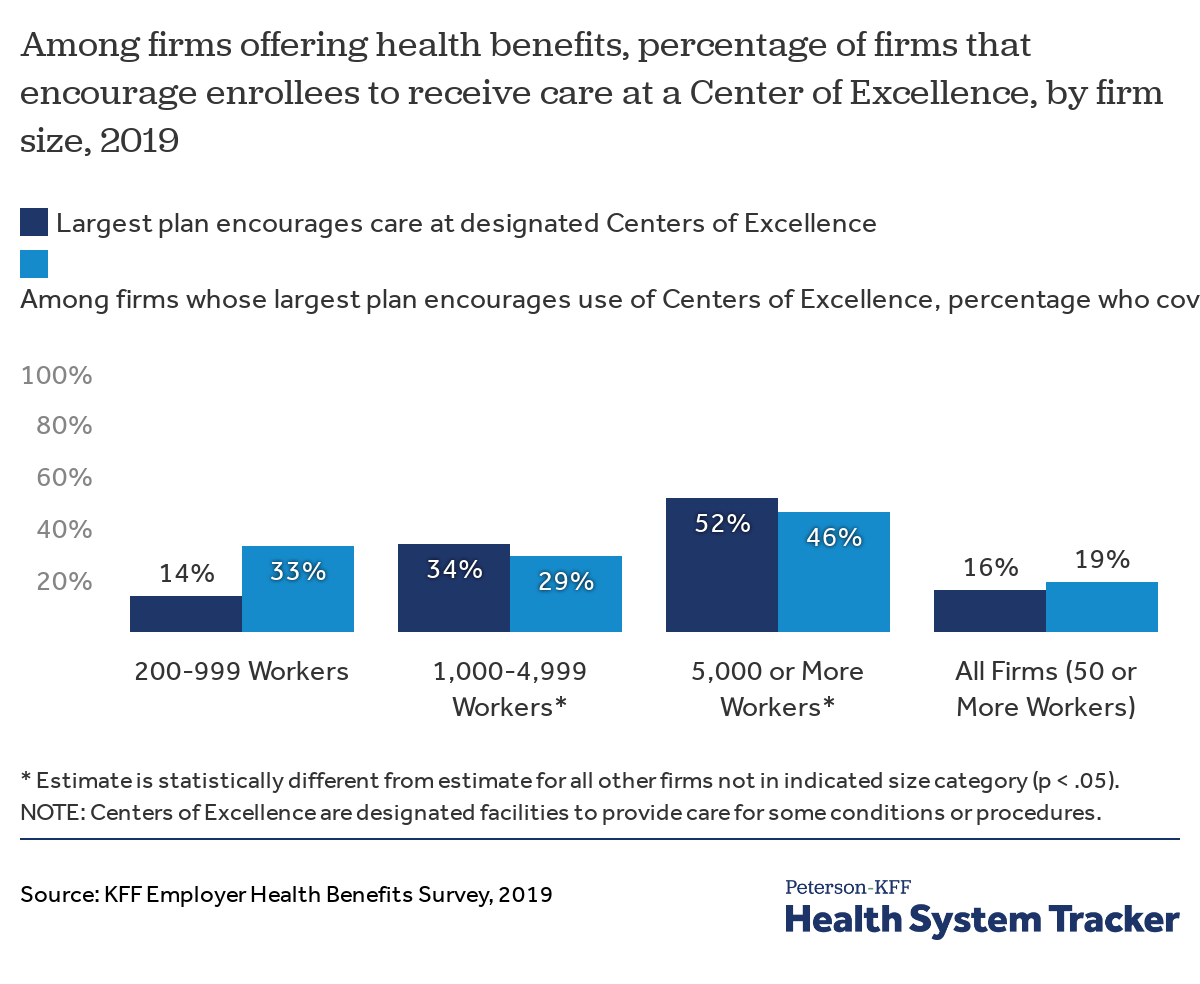

Firms can designate specific facilities as Centers of Excellence if they provide very high quality or low-cost care, often times for a particular service. Firms will then encourage workers to receive care for select procedures, such as transplants, at these facilities by offering significantly lower cost sharing than is otherwise available at their in-network hospitals. Some employers, particularly very large ones, have seen drastic reductions in unnecessary care and expenses after adopting Centers of Excellence. According to the 2019 survey, 16% of firms with 50 or more workers designated facilities as Centers of Excellence. Of those firms, 19% further incentivized their workers to receive care at Centers of Excellence by offering to covered travel and lodging expenses.

Approximately 1 in 5 offering firms encourage employees to use a Center of Excellence

While some focus group participants worked for employers with Center of Excellence programs, others cited logistical challenges with incorporating them into their networks.

“We may look at the Centers of Excellence, it’s just hard with such a spread out population.” – Analyst, Large Food Services Firm

Employers Direct Contracting with Health Care Providers

Some employers look beyond the network established by their health plan or administrator and contract directly with hospitals, health systems, or clinics to provide services for certain conditions. These arrangements are available to self-funded firms and are negotiated independent of their health plan. An employer may choose to contract directly with a provider or system of providers if it can negotiate a better deal or get better service than it would through its health plan network. An employer with a substantial number of employees may be able to negotiate for favorable prices, shared-risk arrangements, or may gain access to additional services or data. Among large self-funded employers (200 or more employees), 8% had direct contracting arrangements in 2019.

Only a few focus group participants had successfully directly contracted with providers outside of their original networks. These participants said that they were primarily motivated by recommendations from their employees or their doctors.

“We’ve advocated on behalf of our employees to add providers to the network. An employee needed a kidney transplant and the facility close to our employee’s home was very highly rated and out-of-network, and that’s where he wanted to go and felt like he could get the best treatment.” – Director, Large Manufacturing Firm

“We are based in San Diego so we border with Mexico, and there is a clinic in Mexico offering alternatives for cancer treatment and several of our staff members had gone through there, and so we looked into partnering with them to offer that alternative to our staff.” – Assistant Director, Large Entertainment Firm

Eliminating Providers from Plan Networks

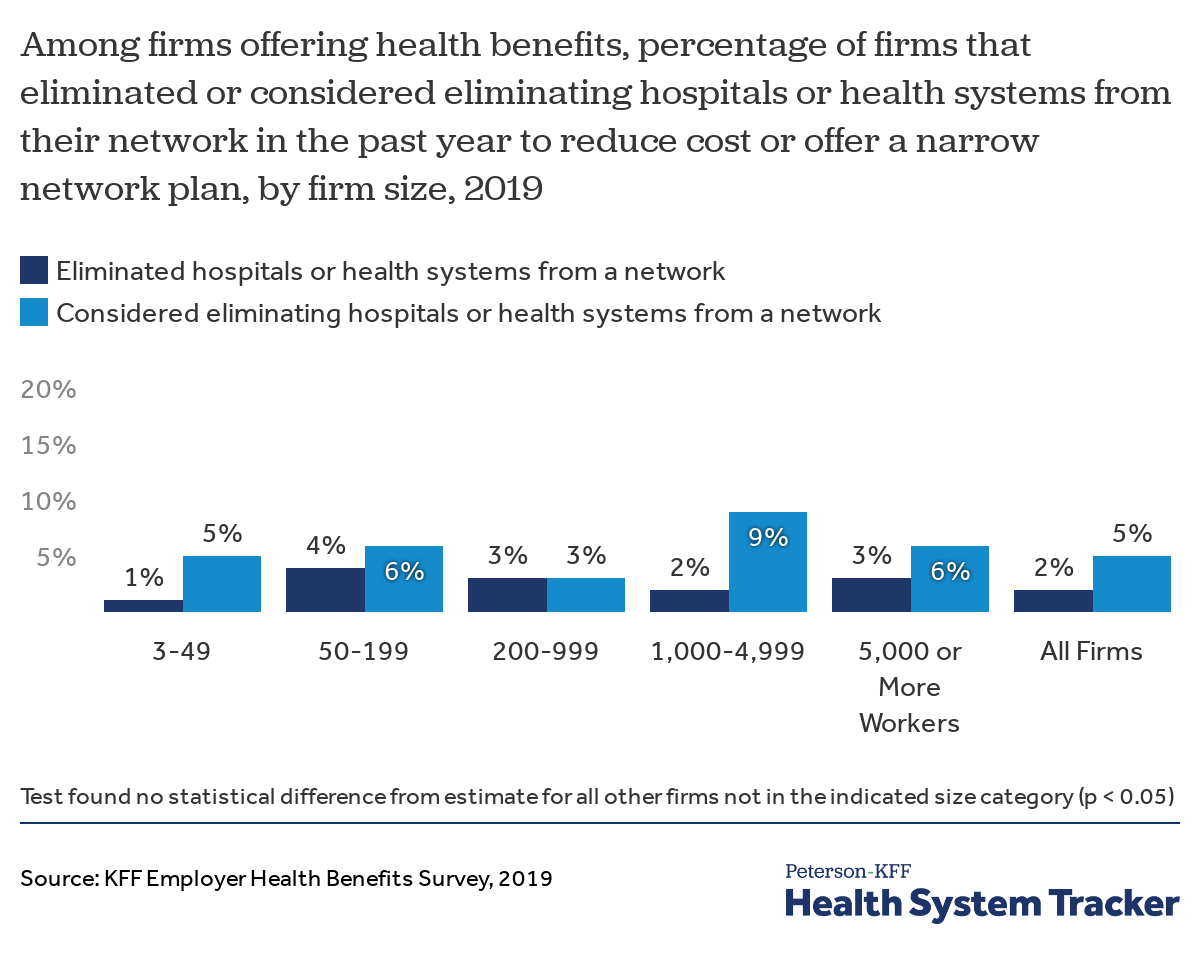

Conversely, employers may be able to improve the value of their health plan by working with their insurance carrier or plan administrator to remove facilities or practitioners with poor practice patterns or excessive rates from the plans’ network. To do this, employers need access to information about the cost and utilization of providers in their plan networks from their insurers or plan administrator.

While it may seem that employers would be interested in dropping poorly performing hospitals or health systems from the networks serving their employees, it rarely happens. Fewer than 2% of firms offering health benefits reported that they or their insurer eliminated a hospital or health system from any of their provider networks in the past year to reduce plan costs. In fact, only 5% of firms that did not eliminate any specific providers from their network have even considered doing so.

Most firms did not eliminate – or even consider eliminating – providers from their networks

The vast majority of focus group participants said they never considered eliminating high cost or low value providers from their networks, and many didn’t know about this option. Among focus group participants, the only instance where a firm had taken steps to exclude a provider was precipitated by drastic price increases.

“One of our local hospitals was purchased by a larger [health system] and their prices were [almost] double even though the hospital was still in-network. We looked at the cost and utilization at their clinics and our broker approached them and said, ‘hey, if you want their business you are going to bring down your prices.’ And they are negotiating.” – Director, Mid-Sized Education Services Firm

Alternative Providers of Care and Telemedicine

Employers and health plans can increase access to services and potentially lower costs by extending their networks to include new types of service providers. In recent years, employers have covered services delivered at retail health clinics, worksite clinics such as those established by employers on or near a work site, and telemedicine services. In addition to being more convenient for workers, these alternative sites of care may also provide access to services at a lower cost than in physician offices or other more traditional settings.

Retail health clinics, which are growing in popularity, are located in retail stores such as pharmacies (e.g., Walgreens, CVS), grocery stores or big-box stores (e.g. Walmart, Target). These clinics typically are staffed primarily by nurse practitioners or physicians assistants and are intended to provide non-emergency care, including preventative services such as vaccinations. Among firms with ten or more workers, 82% cover health care services received at retail clinics, and of those, 16% provide a financial incentive to encourage enrollees to use a clinic rather than visit a traditional doctor’s office.

Some larger employers establish clinics at or near their larger work sites, sometimes sharing the expense with other employers in the area. These clinics may treat workplace injuries or provide additional services to employees and their families. Twenty percent of employers with 50 or more employees report that they had an on-site or near-site clinics at least one work site in 2019.

Telemedicine is the provision of health care services through remote consultation, including the use of video chat or other telecommunications. Proponents of telemedicine believe that it can improve the value and efficiency of health care, for example by conveniently monitoring chronic conditions or triaging and managing non-emergency situations. It also has the potential to increase access to specialty care to areas with limited provider availability. Employers have embraced the concept, with the share of large employers whose plan with the largest enrollment covers telemedicine growing rapidly, from 27% in 2015, to 63% in 2017, and 82% in 2019. Among employers with 50 or more employees that offer telemedicine services in their plans, 48% use incentives, such as lower cost-sharing, to encourage the use of telemedicine. Although employers have been quick to embrace telemedicine’s potential, employees have been slow to respond: less than 1% of enrollees in large employer plans used an outpatient telemedicine office visit in 2016.

Due to time limitations, we didn’t discuss the use of retail or on-site/near-site clinics with the focus group participants. For telemedicine, focus group participants reported mixed results. Most participants expressed excitement about telemedicine’s potential advantages, especially for lower-wage workers who cannot afford the cost of a comprehensive health plan. Invariably though, all participants reported that utilization rates were low. Multiple firms participating in the focus groups actually dropped coverage for telemedicine because the low utilization rates did not justify the cost. Some focus group participants said their plans either charged the same cost-sharing or more for telemedicine services than in-person visits. However, focus group participants who charged lower cost sharing for telemedicine saw promising trends in the take-up rate.

“We pulled in telemedicine too so that our employees can, for the common easy things, they don’t have to go to the ER which is a lot more expensive, and they are able to utilize something on their phone to diagnose a sore throat or whatever.” – Representative, Large Manufacturing Firm

“The only option [our hourly employees] have is the Minimum Essential Coverage, and then telemedicine becomes critical in that because that’s where they are going to be able to get that routine office visit, those kind of immediate fixes without any costs, where under a MEC plan if they go to an urgent care they are going to burden that cost 100%.” – Manager, Mid-Sized Utilities Services Firm

“We changed from $15 copays, and we offer it at $0 and it has like tripled the usage.” – Director, Mid-Sized Education Services Firm

Considerations and Challenges to Adopting Cost-Reducing or Quality-Improving Approaches

Health plans design their provider networks so that they have options that will be attractive to their employer clients. Those clients, in turn, are attentive to the needs and desires of their employees and their family members, as well as to the costs of the benefit plan. Health plans generally create multiple plan options, often with somewhat different networks, to accommodate the various ways that different employers balance those considerations.

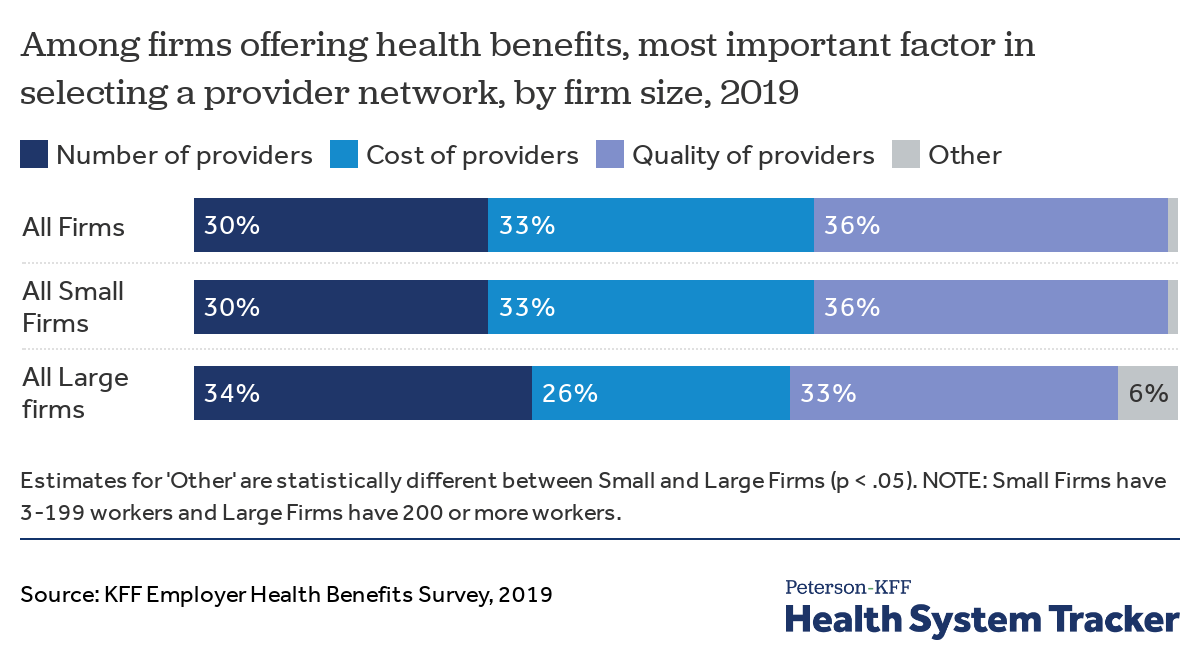

While the health policy literature often focuses on ways that health plans and employers can use networks to increase efficiency or reduce costs, employers have a more nuanced view when judging provider networks. When asked about the most important criteria for evaluating a provider network, roughly equal shares of small and large employers say the number of providers, the cost of providers, and the quality of providers.

Firms are evenly split among the most important factors in selecting provider networks: number and convenience, cost, and quality

This balanced view makes sense because employers view health insurance as a valuable employee benefit that is important to attracting and retaining workers. While health benefits are clearly expensive and employers are always interested in ways to reduce costs, employers still need to balance potential cost savings against the risk of worker dissatisfaction. This is particularly important in the current tight labor market, where recruitment costs are high and there is a premium on retaining current employees. As some focus group participants noted, this also applies to firms recruiting workers in lower-wage industries.

“We’ve had a few different brokers and it seems like there’s a push for financials being the number one factor. But for our organization we’re driving recruitment and retention with the benefit plans because pay is never going to be the highest. So it’s interesting to me because it seems like that is a carrot that is out there, but it is not a carrot for us.” – Director, Mid-Sized Educational Services Firm

“We have several locations where we will start out with one to three employees and those locations aren’t necessarily going to grow to be really large. That’s why we want to make sure that we have a broad network as opposed to a narrow network, so we can say that ‘okay, you are going to have flexibility to likely go to your doctor.’ We look at costs, but when it comes to network we defer cost being the number one factor over network and the availability of network from a recruitment perspective.” – Director, Large Rental and Manufacturing Firm

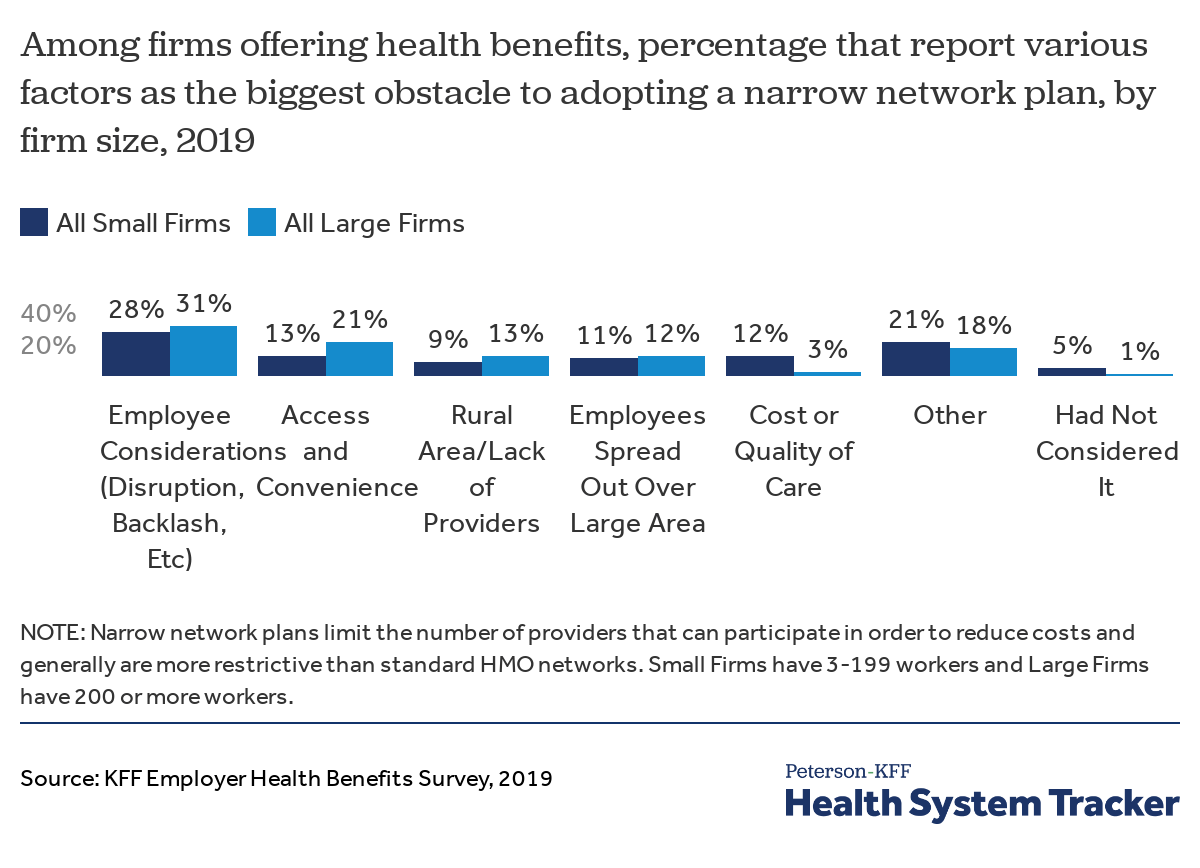

Viewed through this lens, it’s not surprising that strategies such as tiered or narrow networks, which have the greatest potential for employee disruption and dissatisfaction, have low adoption rates despite the potential to reduce costs or improve quality. Concerns about employee backlash and access and convenience for employees are among the most important obstacles identified by employers to adoption of a narrow network plan. In contrast, strategies that add provider options and have no downside for employees, such as telemedicine and retail health clinics, are widely adopted.

Firms cite concerns over disruption, employee backlash, access, and convenience as some obstacles to adopting narrow networks

Administrative Capacity and Expertise

Employers’ size and management resources also affect their ability and capacity to identify cost and quality issues and advocate for changes in health plan networks. Smaller and mid-sized employers generally must choose from network options offered by the insurers serving their areas. Larger employers will have more opportunity to customize their networks by working with their health plans and plan administrators, with the largest employers having the most leverage. Options may be limited even for some very large employers, however, if their workforce is widely dispersed or includes numerous rural areas. Many smaller and mid-sized employers also lack the expertise or awareness to exercise authority over their health plans or providers in their network, and, as a result, are frequently reliant on brokers or third party administrators. Even some employers that most would view as large may not have the internal capacity to engage meaningfully on network issues with their health plans and plan administrators. The vast majority of both small and larger employers use a broker or consultant to help them choose a health plan.

For many focus group participants, brokerage firms played a large role in designing and evaluating provider networks. Some focus group participants indicated that their brokers helped negotiate with carriers and providers, or commonly sat in on discussions with the carrier to offer guidance. In general, there were mixed reviews about the effectiveness and quality of relationships that exist between firms and their brokers, but many focus group participants seemed to believe that they were powerless without them.

“[With regards to eliminating providers] I don’t even think we knew to ask the question.” – Director, Large Rental and Manufacturing Firm

“I was just texting our executive director right now saying, ‘wow I didn’t realize we have all of these extra options in terms of benefits because our broker, basically, once a year says ‘okay, these are your options.’” – Assistant Director, Large Entertainment Firm

“I think that narrowing networks or cutting people from your networks is new to me because I always felt that we were at the whim of the provider, that if they are in the network they are good to go and that we didn’t have the ability to control that.” –HR Representative, Mid-Sized Hospitality Firm

“We’ve met with [our broker] to say, we need the honeymoon phase back again. We are relying on you for this information. I’m an HR director, I’m not an expert in benefits, I try to be, but I also have to recruit and retain my talent, too. There’s other things I need to be doing.” – Director, Large Manufacturing and Wholesale Firm

Focus group respondents also identified administrative challenges in implementing and communicating network changes. Tiered or narrow networks are challenging not only for employers to establish, but also for employees to navigate. It requires significant energy and sophistication to identify high-performing providers or networks, especially for firms that operate in multiple locations. On top of that, it is difficult to communicate changes in network design to a large workforce, detailing which providers are new or no longer covered. Human resource departments may not have the expertise or resources required to adopt sweeping network changes. Several focus group participants who had employees spread out across multiple states echoed these sentiments.

“I don’t think we have thought about it because we have over 100 locations all across the U.S., so logistically it would be challenging to pick someone in each market.” – Manager, Large Manufacturing Firm

“I know [our carrier] has the option out there to restrict certain hospitals in an area, but with us with over 1,000 employees spread out over the U.S., we wouldn’t look at it just because of a communication issue, to try to communicate who they can and can’t go to.” – Recruitment Specialist, Large Construction Firm

“Engagement is really hard for us because we have a few hundred stores, there’s 100 employees at each one and none of them are in HR. So we are relying on the bookkeeper in the store to disseminate a lot of the information. A lot of our people don’t have email addresses and we have had internal push back on trying to get our employees’ mobile phone numbers. So we have morning huddles and things and we can keep pushing stuff but we don’t know if it’s being discussed.” – Analyst, Large Food Services Firm

Availability of Information

Even employers that want to push for network changes to improve quality or increase efficiency may not have the information they need to assess their current networks or the providers within them. Employers must have access to information about the performance of health systems or individual providers to determine whether including or excluding them will improve the value of their health plans. This information can come in various forms, including claims data or online tools that rank providers on cost or quality measures.

Aside from the limited information on quality available in online tools designed for enrollees, focus group participants were generally unable to identify any quality information available to them. Focus group participants were more likely to receive rankings or metrics on providers’ cost or utilization rates rather than quality outcomes from their insurers or administrators. Some focus group participants reported that this cost and use information comes to them only during regularly scheduled reviews with carriers or brokers, but outside of these meetings, the firms have to request these metrics in order to receive them. Very few participants had independent access to the underlying data. Given the incompleteness of the rankings and reliance on brokers or carriers to analyze the underlying data, it would be very difficult for most focus group participants to construct a picture of how well a health system or network is performing.

“[We] get a lot of data. We work with [a brokerage firm] so we get quite a bit of information and we do quarterly reviews…but I have never seen ‘How is this network performing as a whole,’ whether it’s an A, B, or a C.” – Vice President, Large Consulting Firm

“We have no visibility [with Carrier A], of any kind. We had [Carrier B] before but the problem was trying to get visibility into the other states because it’s patch worked. With [Carrier C] you can look up any doctor and see what their rates are and their outcomes.” – Analyst, Large Food Services Firm

“We get a little bit of the utilization information from [Carrier A], but that has come with a lot of requesting and pushing and prodding. In our HSA plan [with Carrier B] we don’t get information into rates, but more utilization, and we also have had to do a lot of follow-up and a lot of requesting to get that. Without that we would not be getting anything.” – Manager, Large Transportation Firm

Geographic Considerations

Another challenge for health plans is ensuring they have networks that are large enough to serve employers with workers in multiple locations and in rural areas. Many areas have relatively few providers, leaving health plans in a weak position to bargain. Larger plans with multi-state networks have an advantage with employers looking for a single plan, but that may limit the number of options available in some places. The alternative for these employers is to contract with multiple health plans, which is administratively more complex.

“We haven’t explored [tiered networks] because we have limited coverage as is in the areas we are in, so it’s hard to put something like that in place. We also only have one network and unfortunately, a lot of the communities that we serve and our employees are in are desolate. There may be one physician in that community. So that has been a real challenge, finding a network that actually works for all those communities.” – Director, Large Educational Services Firm

“I’m in a very similar situation. We have one network to choose from, but it has to be someone who is able to be out in communities like that. Very, very rural areas that don’t accept everything.” – Representative, Large Management Firm

Similarly, firms whose workforce is spread out over several sites may not be able to engage effectively on issues of network cost and quality because they do not have a sufficiently concentrated interest in the provider network serving any particular area. Their workforce location also may not line up with the areas where health plans have created alternatives such as tiered or narrow networks.

Eleven percent of large firms report that the biggest barrier to adopting a narrow network is that their employees were spread out over a large area or multiple states. The vast majority of focus group participants had employees operating in multiple areas or states, making it difficult to push back on network composition in a focused way.

“[With regards to direct contracting] I don’t know that we would have had the volume in a particular area to do so.” – Director, Large Staffing Agency

“We have two major locations in the U.S. but we have employees spread out in nearly every state, and accessibility to network was a huge issue for us. We struggled with getting network coverage in our secondary state, where we have the second most group of employees. We put out to bid and we had companies that won’t even bid on our business because they can’t provide the network that we need.” – Director, Large Manufacturing Firm

“So we have companies in the U.S. from New Jersey to California and with [Carrier A] we don’t have buying power. We are kind of stuck with [Carrier B], because it is almost 98% of our employees [that] have access to their networks.” – Director, Large Manufacturing and Wholesale Firm

Discussion

Many of the strategies outlined here have the potential to reduce cost and improve quality. While employers have generally adopted coverage for telemedicine and care at retail clinics, many of the strategies that require employers to become more active purchasers, such as direct contracting, developing narrow networks and eliminating providers, have relatively low rates of adoption. Many employers face limitations such as a lack of data, time and expertise to undertake these steps alone. Often times, especially for smaller and mid-sized employers, they are reliant on insurers and consultants to help design and monitor these programs.

Even if firms have the buying power or resources to reconfigure their provider networks, they still face challenges in doing so. All of the network configuration approaches discussed above require difficult trade-offs between the cost, quality, and convenience of health care, decisions on which there is little consensus. On one hand, employers have obvious incentives to cut their health spending, but there is widespread concern over how workers would respond to changes or reductions in their health plan’s provider networks. While workers generally value broader networks, cost may be an increasingly important concern for at least some employee populations. According to a recent survey conducted by KFF and the Los Angeles Times, workers report that cost (36%) has overtaken the choice of providers (20%) as the main reason they chose their health plan, essentially inverting the results from a similar KFF survey in 2003.

Employers have sought to cut costs and ensure appropriate use of service through increased cost sharing and the use of utilization management programs, but the ability of employers to influence the prices of services depends in large part on their ability to negotiate those prices with providers. That has not happened on a large scale, possibly in part because unemployment has been low and employers have been attracting and retaining workers. It’s possible employers might turn more to network strategies if the labor market loosens, or if there is growing resistance to continued increases in deductibles as a strategy to constrain the cost of health benefits.

Methods

The 2019 Employer Health Benefit Survey is a nationally representative survey of trends in benefit designs, offer rates, and costs of health plans offered by both small and large companies. This year, with support from the Peterson Center on Healthcare, KFF added several new questions to the survey to examine how employers make decisions around provider networks as a way of influencing costs/efficiency and improving quality. The 2019 survey included 2,012 interviews with nonfederal public and private firms. For more information on the employer health benefit survey, please visit www.kff.org/ehbs.

In addition to this year’s survey, we organized three focus groups at large human resource conferences, to explore how employers approach trade-offs between the cost, access, and quality of care for their employees. Two focus groups were conducted at the Society for Human Resource Management’s (SHMR) 2019 Annual Talent Conference held in Nashville, Tennessee. The third focus group was conducted at Human Resource Executive’s (HRE) 2019 Health Benefits Leadership Conference in Las Vegas, Nevada.

The authors would like to thank the Society of Human Resource Management (SHRM) and Human Resource Executive (HRE) for their assistance in organizing the focus group discussions.

The Peterson Center on Healthcare and KFF are partnering to monitor how well the U.S. healthcare system is performing in terms of quality and cost.