Although older adults have been at the highest risk of becoming seriously ill and dying from COVID-19, many younger people have had their lives cut short by the illness. And, while much attention has been paid to the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on people of color, it also is important to consider the prematurity of these deaths. As a measure of the impact of the pandemic, mortality rates alone do not tell the full story as they do not incorporate the age at death. One can also look at the premature mortality rate or the rate of death below a certain age. Another measure, years of life lost (derived from counts of deaths at each age that were in excess of deaths observed in typical years), measures the degree of prematurity of deaths during the pandemic.

In this brief, we examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic by race and ethnicity through the lens of premature mortality, using the measures of premature mortality rate and years of life lost among excess deaths that occurred during the pandemic.

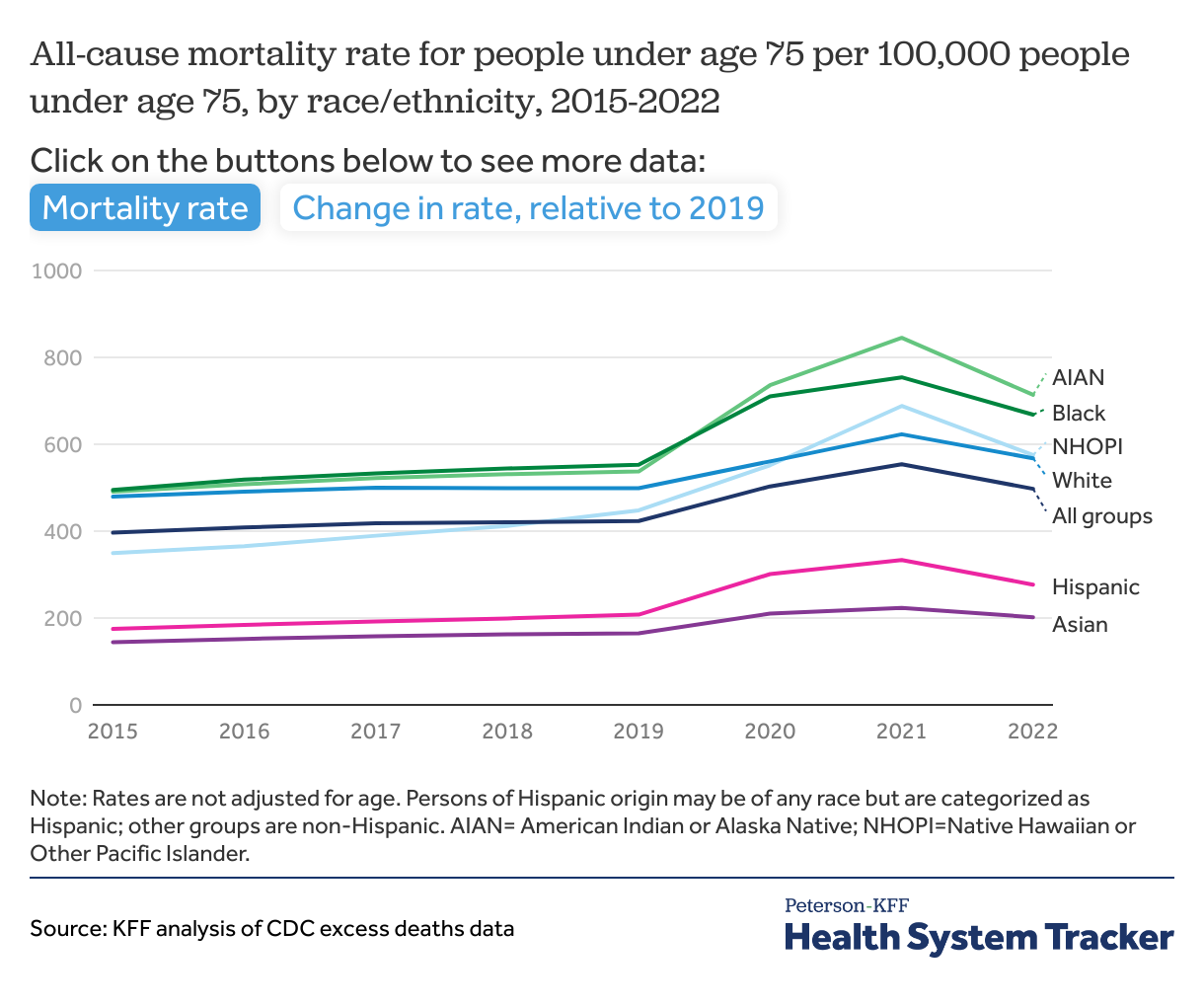

We count premature deaths as deaths that occurred before the person had reached age 75. This approach, discussed more in the Methods section, provides a uniform measure of the extent of premature death during the pandemic, although in a sense every death due to COVID-19 has been premature. Before the pandemic, most racial and ethnic groups had life expectancies of about 75 years or longer, although American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) people had a life expectancy of 71.8 years. For the premature mortality rate, we calculate the all-cause, age-specific mortality rate for people under age 75 using weekly counts of death from 2015 to 2022.

We also look at the number of years of life lost before age 75, basing this part of the analysis on excess mortality data from March 2020 through December 2022 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Excess deaths are those above CDC’s estimate of expected count based on pre-pandemic mortality averages. While most of the excess deaths during the pandemic have been due to COVID-19, deaths from drug overdose, suicide, heart disease, and liver disease also increased during this period. Here, we look at years of life lost due to all causes from March 2020 through the end of 2022. Using age 75 as a uniform benchmark is comparable to how OECD presents international comparisons of premature mortality. American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) people had a lower average life expectancy before the pandemic than this age limit. Using the same age limit across groups avoids incorporating pre-existing disparities. The social and economic forces driving disparities during the pandemic are likely related to the lower life expectancy as well.

While the pandemic has had devastating effects across all racial and ethnic groups, we find significant racial disparities in premature death during the pandemic. Consistent with pre-pandemic trends, some communities of color faced higher premature death rates during the pandemic than their White counterparts. For all groups of color, though, the pandemic was associated with a steeper increase in the premature death rate than for White people. The increase in the premature death rate for Hispanic people (33%) was over twice that of White people (14%) from 2019 to 2022.

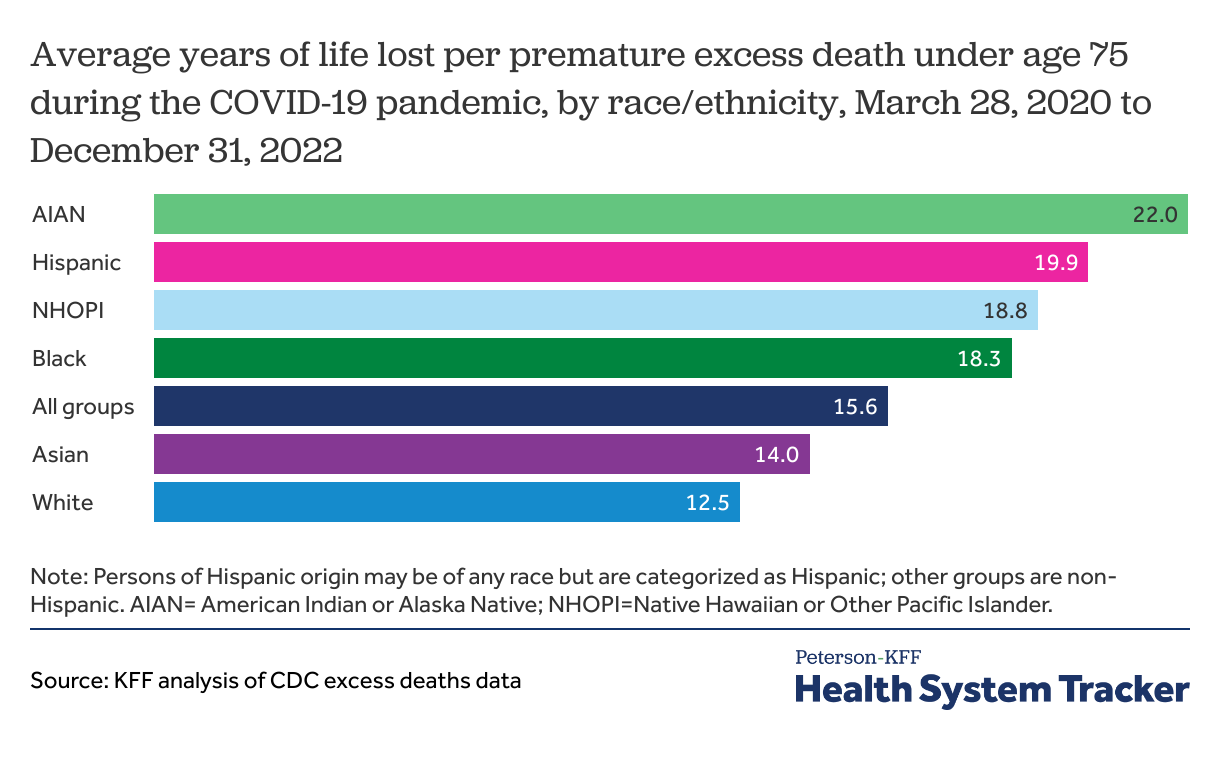

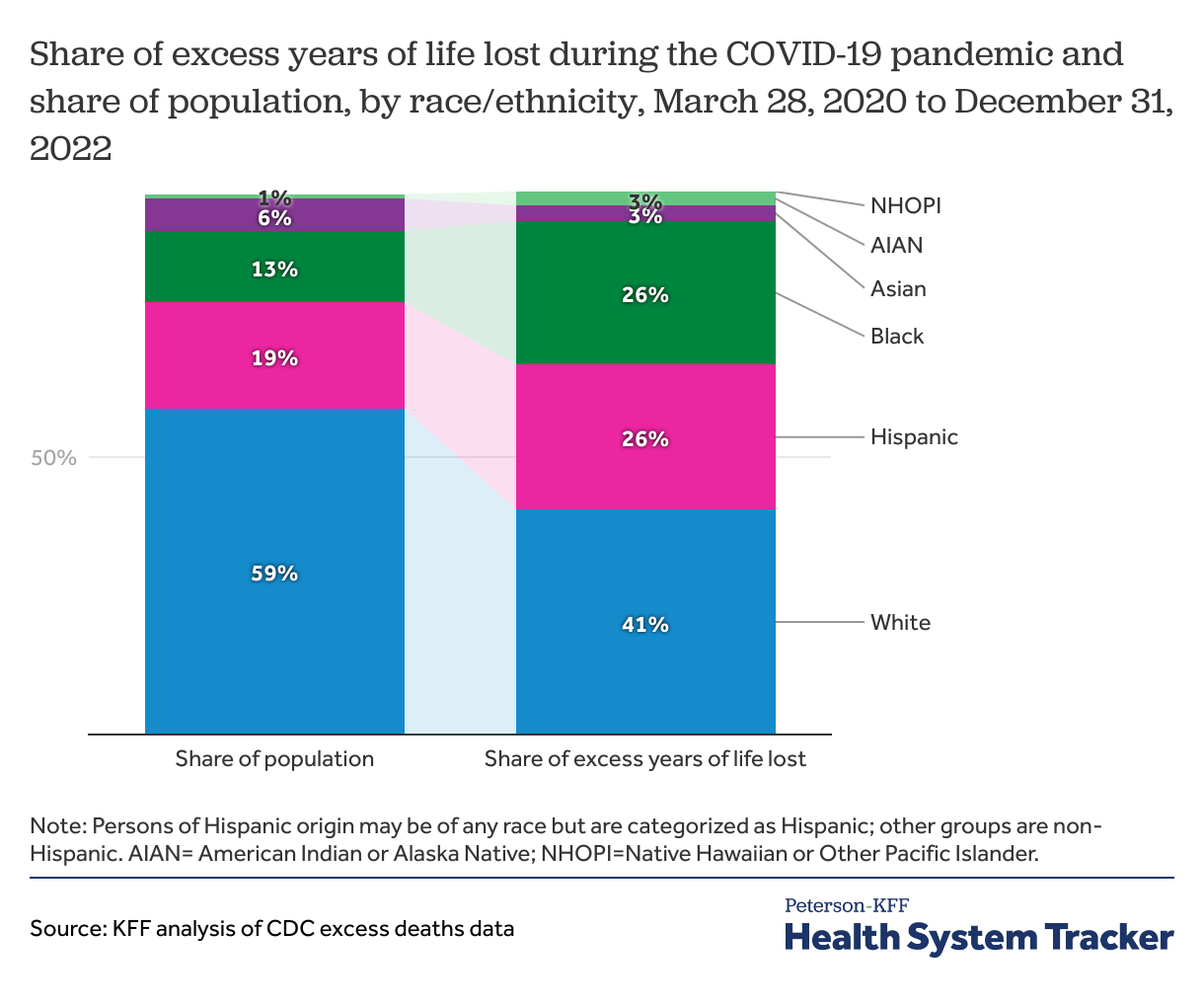

We also find, among excess deaths during the pandemic, people of color who died prematurely lost more years of life than White people, on average. For example, using excess mortality data, premature deaths among White people resulted in an average of 12.5 years of life lost, while premature deaths among Hispanic people resulted in 19.9 years of life lost and premature deaths among AIAN people resulted in an average of 22.0 years of life lost before age 75. While communities of color make up about 40% of the U.S. population, they experienced 59% of the years of life lost during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic is associated with faster increases in premature mortality rates for communities of color than for their White counterparts

The premature mortality rate (mortality rate for people under age 75) by racial/ethnic group was relatively stable in the years leading up to the pandemic, although racial disparities existed. In 2019, the age-specific premature mortality rates of AIAN and Black communities were 537 and 553 per 100,000 people —somewhat higher than that of White people at 499 per 100,000 people.

While all groups experienced an increase in premature mortality, the rate rose more for people of color than for White people. Between 2019 and 2022, the all-cause mortality rate among people under age 75 increased by 33% for Hispanic and AIAN people, 28% for Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) people, 22% for Asian people, and 21% for Black people, in contrast to a 14% increase for White people. As of 2022, AIAN and Black people had the highest rates of premature mortality, while Hispanic and Asian people had the lowest rates of premature mortality, consistent with the pre-pandemic trends.

During the pandemic, premature deaths among people of color resulted in more years of life lost than among White people

Measures of years of life lost can provide information on how premature these deaths are. We find that among excess deaths from March 2020 through the end of 2022, people who died prematurely lost an average of 15.6 years of life before age 75.

Among premature excess deaths during the pandemic, AIAN and Hispanic people lost the most years of life compared to other racial and ethnic groups. Premature excess deaths among AIAN people resulted in an average of 22.0 years of life lost and premature excess deaths among Hispanic people resulted in an average of 19.9 years of life lost. By comparison, White people lost an average of 12.5 years of life from premature excess deaths during the pandemic.

Although people of color make up about 40% of the population, they account for 59% of excess years of life lost during the pandemic

Through the end of 2022, we estimate 14.8 million years of life were lost during the COVID-19 pandemic as a result of excess deaths, with a disproportionately large share of these years of life being lost by people of color. We find that through the end of 2022, 6.1 million years of life were lost among White people, 3.9 million years of life were lost among Hispanic people, and 3.8 million years of life were lost among Black people. White and Asian people accounted for a smaller share of years of life lost compared to their share of the total U.S. population.

In contrast, AIAN, Black, and Hispanic people made up larger shares of years of life lost due to excess deaths during the pandemic than their share of the total population. AIAN people made up 3% of total years of life lost but just 1% of the population. Black people made up 26% of the total years of life lost but just 13% of the population, and Hispanic people accounted for 27% of years of life lost in contrast to 19% of the population.

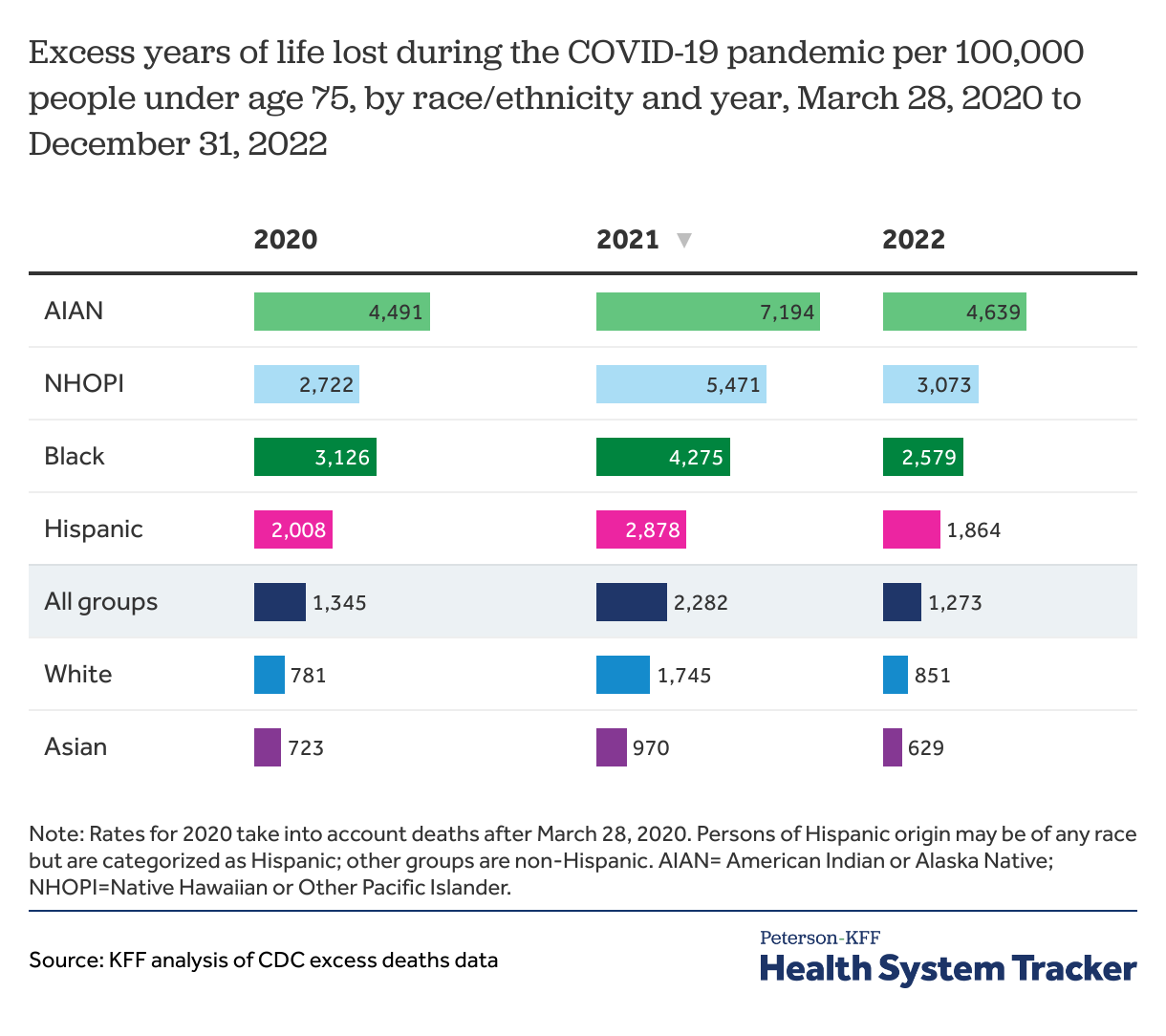

Racial and ethnic disparities in years of life lost have persisted throughout the pandemic

Despite variation in rates of years of life lost over the course of the pandemic, AIAN, NHOPI, Black, and Hispanic people consistently had a higher rate of years of life lost due to premature excess deaths compared to the total population and compared to White and Asian people, between 2020 and 2022. AIAN communities had the highest rates compared to other racial and ethnic groups throughout the pandemic, followed by NHOPI, Black, and Hispanic people.

Discussion

Reporting of excess deaths aggregated for all people may hide any disparities that exist by racial and ethnic groups. There are likely numerous factors contributing to these large racial/ethnic disparities in years of life lost during the pandemic. During the pandemic, younger people of color may have been more likely to be exposed to the virus as they are more likely to have employment and living conditions that increase risk of exposures. Additionally, some groups of color have higher rates of underlying conditions that may have increased the risk of severe illness and death if people contracted the virus. Disparities in COVID-19 vaccination may have had varying effects throughout the course of the pandemic. Though there were large gaps in vaccination rates between Black and Hispanic people and White people in the initial phases of vaccine rollout, those rates did not adjust for age and the differences narrowed and eventually reversed for Hispanic people.

People of color also face broad disparities in access to health care as well as in social and economic factors that drive health, which may contribute to disparities in years of life lost due to premature death during the pandemic. For example, nonelderly AIAN, Hispanic, and Black people are more likely than their White counterparts to be uninsured and many groups of color fare worse than White people across other measures of access to, use of, and quality of care, including not having a regular doctor or health care provider and going without care due to cost. Many groups of color also fare worse than White people across social and economic measures that drive health. For example, Black, Hispanic, AIAN, and NHOPI people are more likely than their White counterparts to have incomes below poverty, have lower rates of home ownership, and to live in crowded housing arrangements.

Although most excess deaths during the pandemic were caused by or related to COVID-19, other factors not necessarily directly related to COVID-19 explain some excess deaths during the pandemic. For example, while drug overdose death rates increased across all racial and ethnic groups during the pandemic, the increases were larger for people of color compared to White people.

People of color have borne a disproportionate loss of life during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially among younger ages. The finding that people of color experienced higher rates of years of life lost from excess deaths during the pandemic has significant implications for the health and economic well-being of those family members left behind. Higher rates of premature deaths in some groups will likely lead to long-lasting and generational impacts and may contribute to widening health and economic inequities moving forward.

Methods

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) data on excess deaths associated with COVID-19 were used to calculate excess deaths between March 28, 2020, and December 31, 2022. For each year, from 2015 to 2022, we calculate the premature mortality rate as the number of deaths under age 75, divided by the 2019 Census population under age 75, for each race/ethnicity group.

Excess deaths were calculated as the observed count of deaths beyond the average number of deaths in 2015-2019. CDC excess death data by age groups, race or ethnicity, and week were used to assess deaths within race or ethnicity groups. These excess death counts were used to calculate years of life lost during the COVID-19 pandemic. CDC excess death data by age groups, race or ethnicity, and week include data who identify as an “Other” racial or ethnic group. The “Other” group was excluded as they were not included as category in OMB standards. We examined excess deaths along broad racial/ethnic lines, but there may be variations within these groupings. For example, even as Asian people may have experienced lower rates of years of life lost as a broad group when comparing to other groups, these findings may mask differences among subgroups of the population.

For excess years of life lost calculation, excess death counts were multiplied by the distance between the mid-point of the age groups to the age standard of 75 and summed within each age and race or ethnicity group. Age 75 was chosen as most racial and ethnic groups had life expectancies above this age prior to the pandemic. Additionally, it is similar to the OECD Health Statistics methodology for calculating potential years of life lost. Setting a standard age across racial and ethnic groups allows for the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on life expectancy to not bias this analysis.

Persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race but are categorized as Hispanic for this analysis; all other groups are non-Hispanic. CDC data on population counts by age and race or ethnicity were used to find years of life lost rates per 100,000 people.

The Peterson Center on Healthcare and KFF are partnering to monitor how well the U.S. healthcare system is performing in terms of quality and cost.