Millions of people in the United States live with mental health diagnoses, with about one third of adults reporting symptoms of depression and/or anxiety. Among these adults, over 20% report an unmet need for counseling or therapy.

Private insurance covers the majority of nonelderly adults (58%) in the United States, and many enrollees experience difficulty affording care and navigating their coverage. Additionally, people with private insurance often face challenges finding mental health care providers in their insurance networks and are more likely to go out-of-network or self-pay for mental health services compared to other health care services.

In this brief, we explore health spending among privately insured adults treated for depression and/or anxiety. We include nonelderly adults with large employer plans using claims from the Merative MarketScan Commercial Database in 2021. These findings only include services that enrollees claim under their employer coverage, and we are therefore likely underestimating utilization of, and spending on, mental health services.

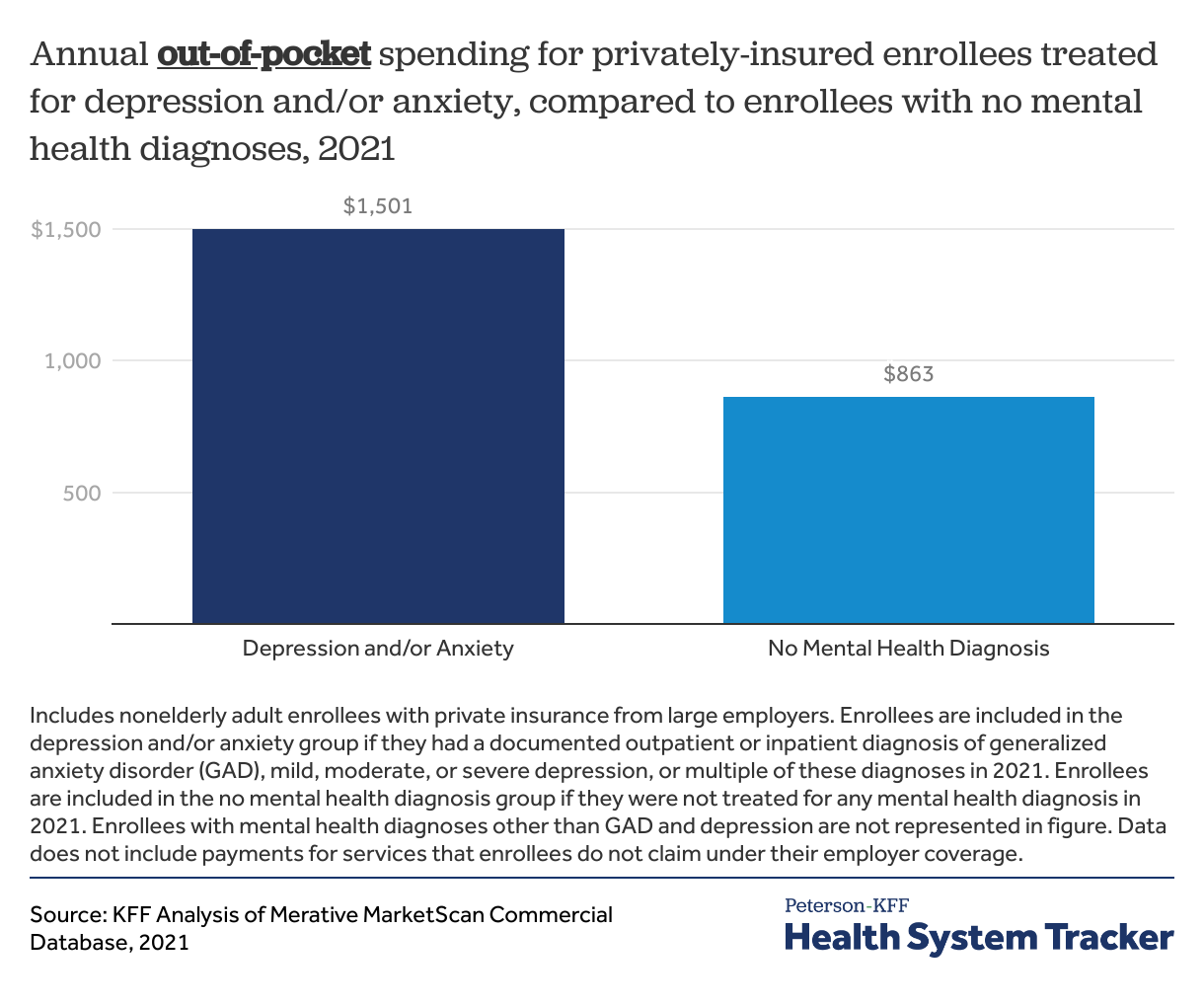

Enrollees who were treated for depression and/or anxiety in 2021 had almost twice as much annual out-of-pocket spending compared to enrollees who were not treated for a mental health diagnosis ($1,501 versus $863). Out-of-pocket spending and service utilization increased with depression severity. Mental health conditions often co-occur with physical health problems, so increased spending may reflect worse physical health in addition to mental health. Psychotherapy was the most common, and most costly outpatient service, with annual costs totaling $1,507 on average per enrollee (including $348 out-of-pocket), though this does not include any therapy where the enrollee paid fully out-of-pocket without submitting a claim to their insurer. We also find that the majority of psychotherapy (61%), psychiatric office visits (66%), and other mental health office visits (51%) were delivered via telemedicine in 2021, compared to less than 1% before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Privately insured people with depression and/or anxiety spent almost twice as much, out-of-pocket, compared to people without a mental health diagnosis in 2021. Share on XPrivately insured enrollees treated for depression and/or anxiety have high out-of-pocket spending

We look at health spending for two common mental health diagnoses: depression and generalized anxiety disorder (to which we refer as “anxiety” throughout). In 2021, 9% of adults with large employer private insurance had a documented diagnosis of depression and/or anxiety in their outpatient or inpatient care.

We find that privately insured enrollees treated for depression and/or anxiety had almost twice as much out-of-pocket spending in 2021 compared to their counterparts with no mental health diagnoses ($1,501 versus $863). Further, total annual spending – which includes out-of-pocket costs plus the portion paid by insurance plans – was 1.9 times as much as for enrollees with depression and/or anxiety compared to their counterparts ($11,701 vs. $6,174).

In part, these differences are due to greater use of services. For example, on average, enrollees with a documented depression and/or anxiety diagnosis had more than twice as many office visits in 2021 than enrollees with no mental health diagnoses (7.4 visits versus 3.2 visits).

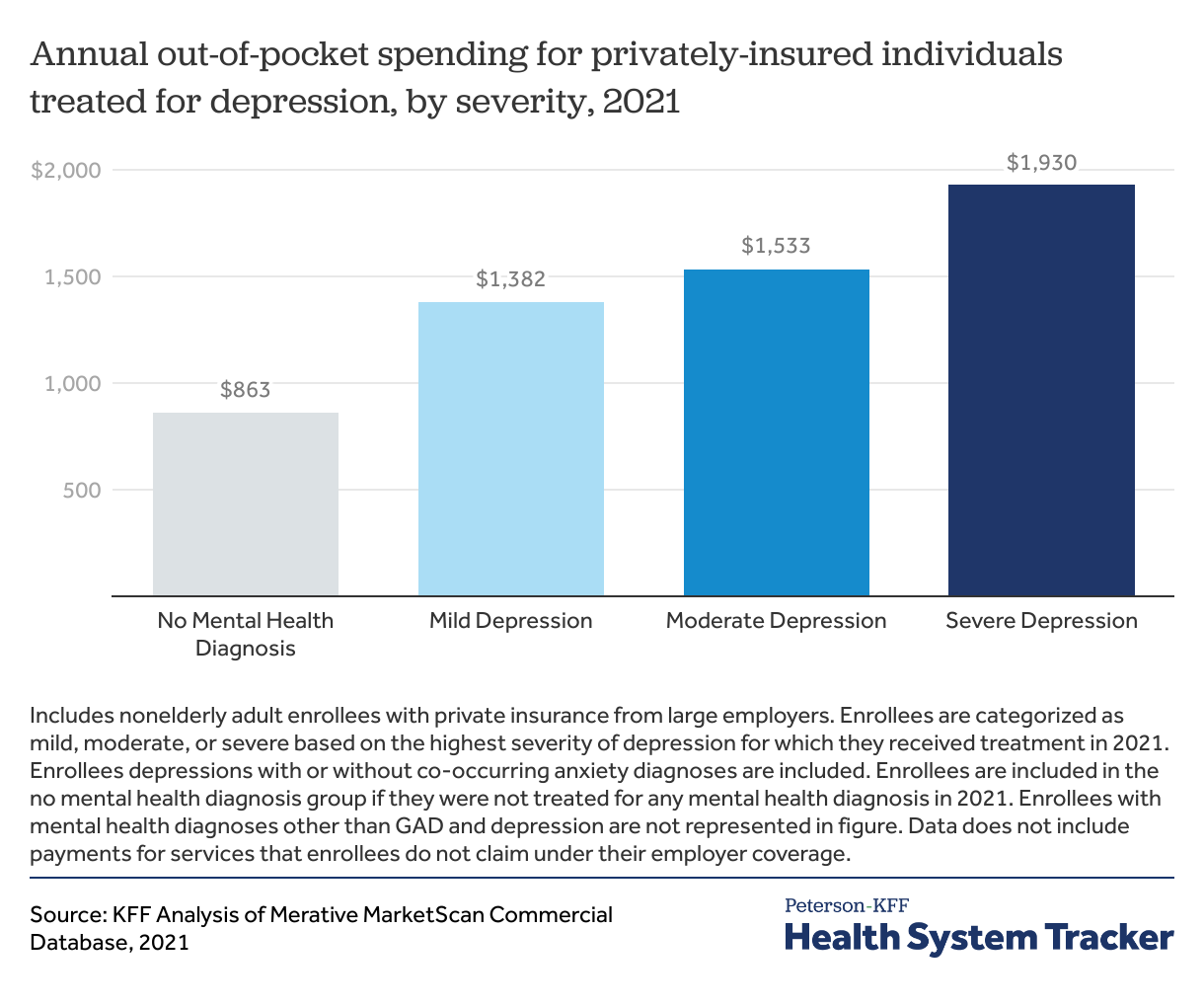

Out-of-pocket spending for enrollees with depression increases with depression severity

We categorized depression severity as mild, moderate, or severe depending on the highest level of depression for which an enrollee was treated in 2021. Of all enrollees with depression (with or without co-occurring anxiety), 21% were treated for severe depression, 56% were treated for moderate depression, and 23% were treated for mild depression.

Enrollees with more severe depression spent more on outpatient care than their counterparts. For example, enrollees with severe depression diagnoses had 40% higher out-of-pocket costs during 2021 than those with mild depression ($1,930 vs. $1,382) and 124% higher out-of-pocket costs than those with no mental health diagnosis. Enrollees with severe depression averaged $17,546 in total annual health spending (including the amount covered by insurance and paid out-of-pocket), compared to $10,464 for enrollees with mild depression.

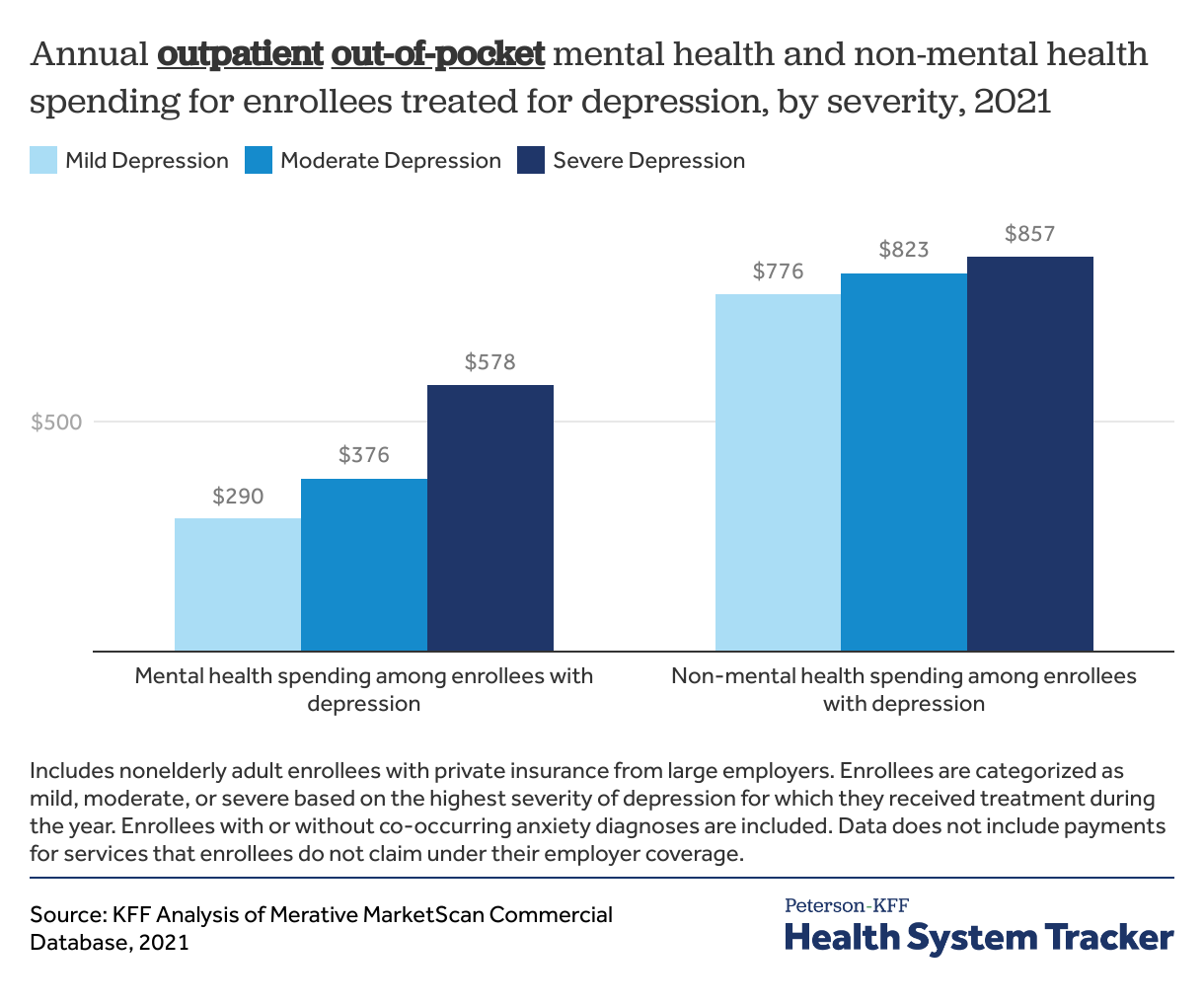

Enrollees with more severe depression spend a larger share of their annual spending on mental health services

Enrollees treated for depression and/or anxiety in 2021 spent the majority of their out-of-pocket costs on outpatient care (78% of out-of-pocket spending), which was similar to enrollees with no mental health diagnoses (75%). Among enrollees treated for depression and/or anxiety, the majority of this outpatient annual spending was for services related to physical health care, rather than to mental health care (mental health services are defined as claims for which the primary diagnosis is a mental health disorder). On average, $376 (or 32%) of outpatient out-of-pocket spending among enrollees with depression and/or anxiety was for mental health services.

Enrollees with more severe depression spent a larger share of their outpatient annual spending on mental health services. For example, enrollees with severe depression spent $578, or 40% of their outpatient out-of-pocket spending on mental health services (not including payments for services that enrollees do not claim under their employer coverage). Conversely, enrollees with mild depression spent $290, or 27%, of their outpatient out-of-pocket spending on mental health services.

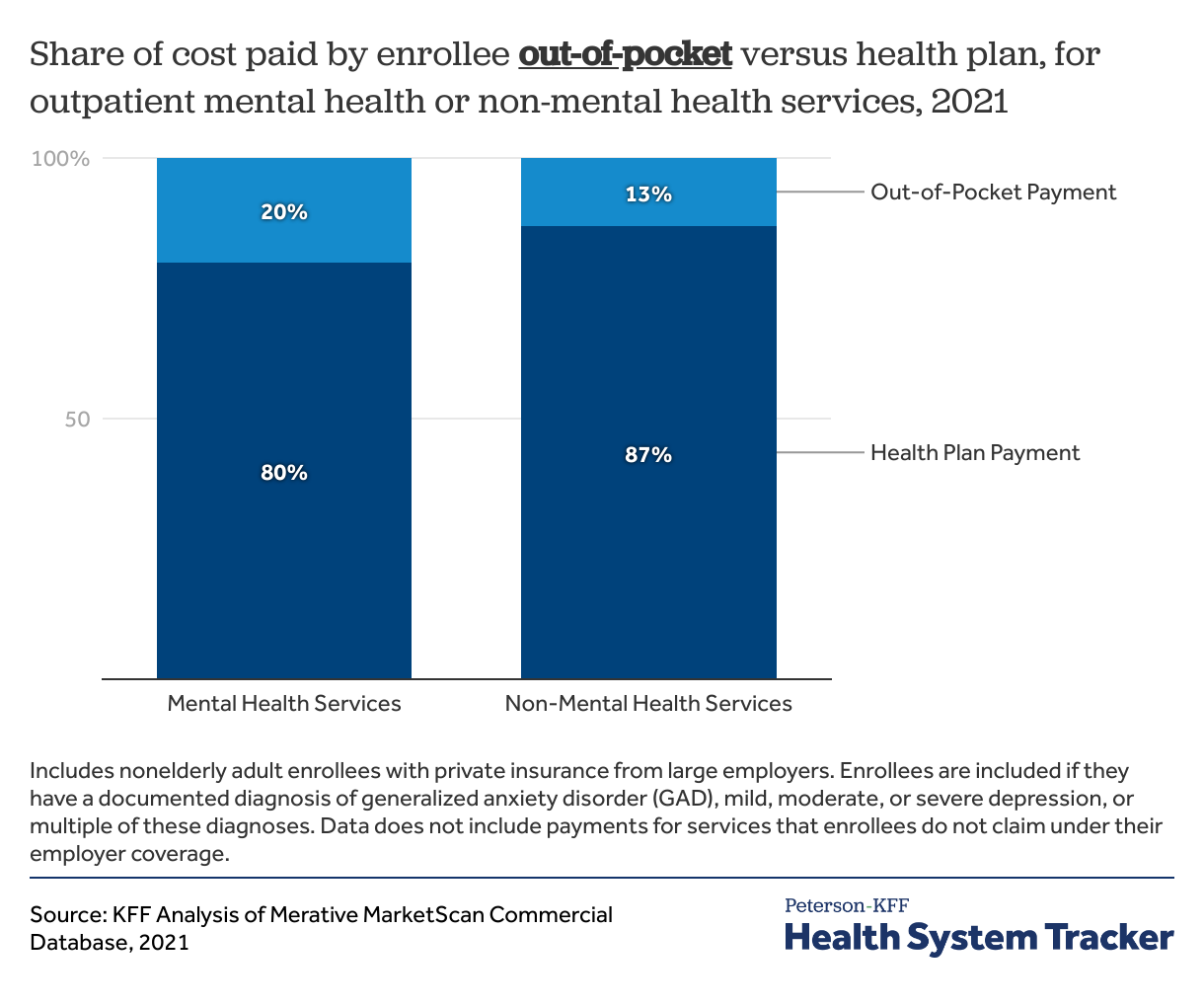

Enrollees treated for depression and/or anxiety pay a larger share out-of-pocket for mental health than for other services

In general, health plans covered a larger share of outpatient non-mental health services compared to outpatient mental health services. Overall, enrollees with depression and/or anxiety paid for 20% of their outpatient mental health services out-of-pocket, with their health plans covering 80%. However, for their outpatient non-mental health services, enrollees with depression and/or anxiety paid 13% out-of-pocket, on average, with their health plans paying 87% of the overall cost. Many common outpatient services are classified as preventive services, which health plans are required to cover with no cost-sharing. Therefore, some of this difference could be because a larger share of non-mental health services are preventive. This is one way in which there may not be true parity in mental health coverage in practice.

Psychotherapy was the most utilized mental health service among enrollees treated for depression

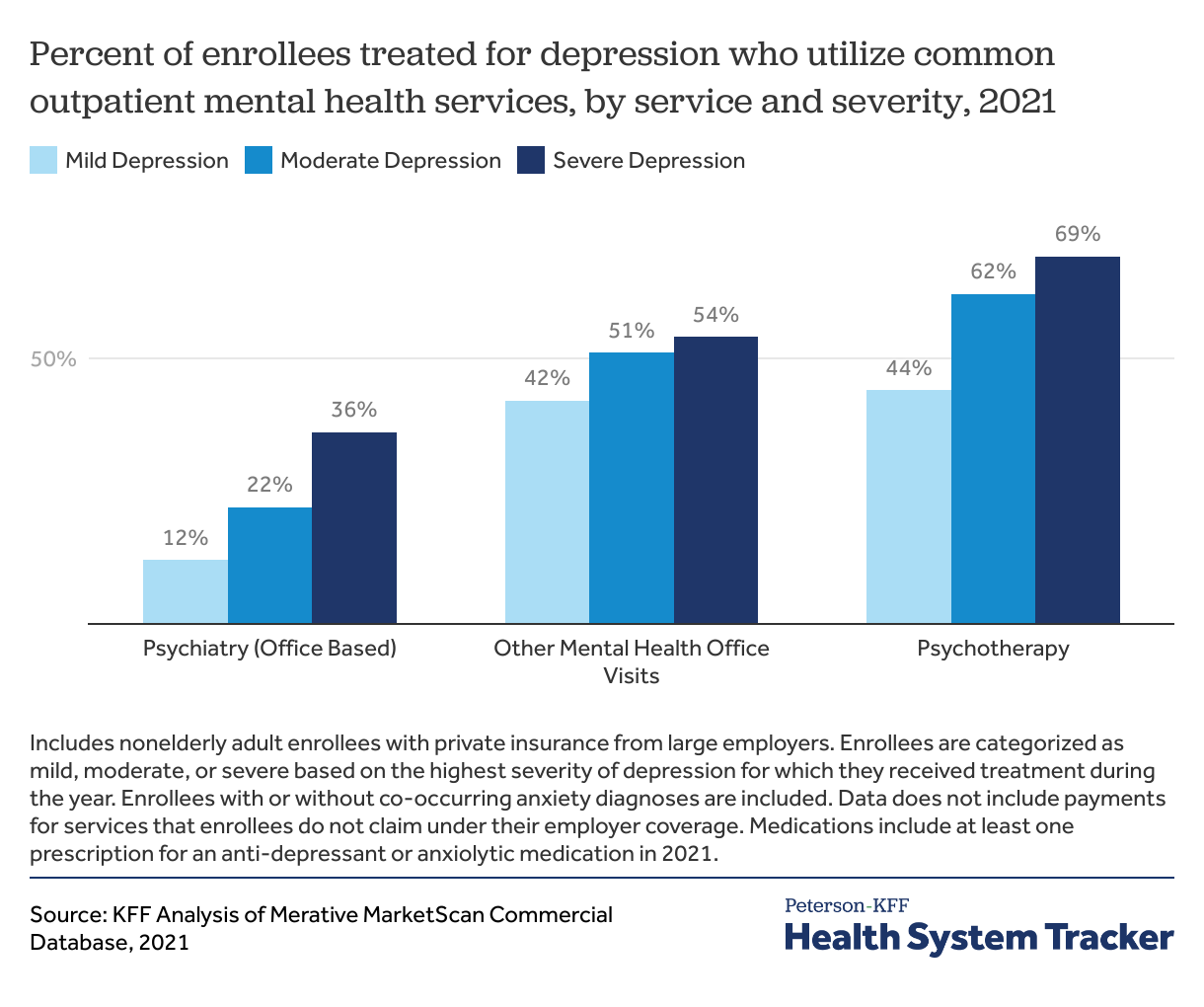

On average, among all enrollees treated for depression and/or anxiety, 18% had a psychiatry office visit during the year, 54% had psychotherapy, and 45% had another type of mental health office visit (defined as non-psychiatrist office visits where the primary diagnosis is for a mental health condition). However, this does not include services for which enrollees self-pay and do not submit a claim to their insurer.

Enrollees with severe depression were 3 times more likely to see a psychiatrist than enrollees with mild depression (36% vs 12%). However, for mental health office visits (non-psychiatrist), enrollees with severe depression were only 1.3 times as likely to have a visit compared to enrollees with mild depression (54% vs 42%).

Most outpatient mental health services were delivered via telemedicine

As demonstrated during of the COVID-19 pandemic, flexibilities offered by telemedicine can help address some of the need for health care, particularly for behavioral health services. The growth in telemedicine for behavioral health visits outpaced other types of care early in the pandemic. Previous KFF analyses found that 55% of employers who offer health benefits believe telemedicine is important to providing access to mental health care.

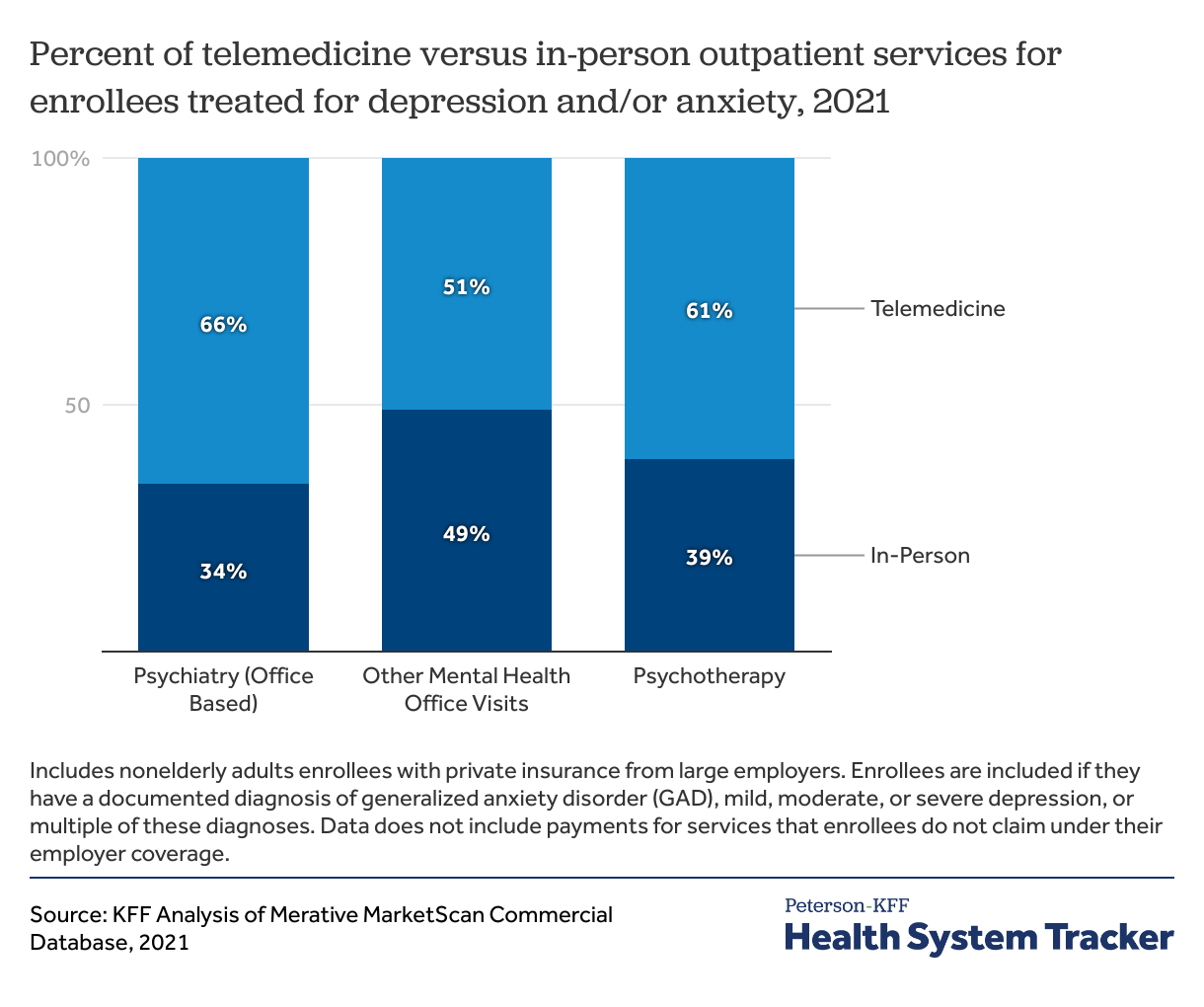

We found that for enrollees with depression and/or anxiety, roughly half of non-psychiatry office visits (51%) for primary mental health diagnoses, were delivered via telemedicine in 2021. A larger share of psychiatry visits (66%) and psychotherapy visits (61%) were delivered via telemedicine. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, less than 1% of these services were delivered via telemedicine.

Overall, mental health services were more likely to be delivered via telemedicine than other outpatient services. For people with no mental health diagnoses, only 9% of outpatient office visits in 2021 were telemedicine.

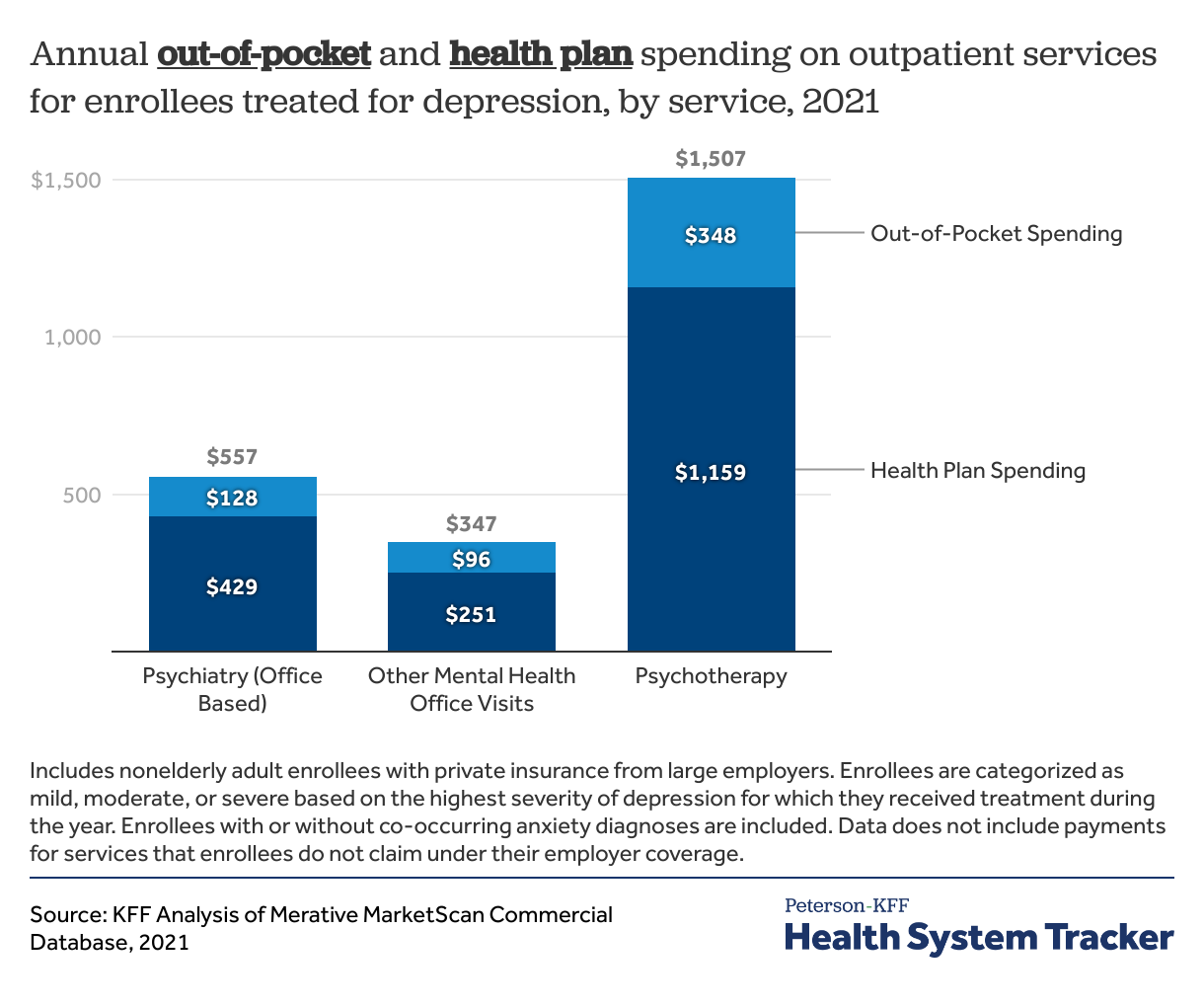

Psychotherapy was the most costly outpatient mental health service, by total and out-of-pocket cost

Among enrollees who were treated for depression and/or anxiety in 2021, psychotherapy was the most expensive commonly used outpatient mental health service. These enrollees paid, on average, $348 out-of-pocket for these services in 2021, and total annual spending averaged $1,507. On average, annual out-of-pocket costs for psychiatric office visits ($128) were more expensive than other mental health-related office visits ($96); differences were similarly reflected in average total annual costs. The annual cost of all mental health services included in this analysis increased with severity of depression. These averages exclude services that were not billed to an enrollee’s health plan.

Anti-depressants and anti-anxiety medications were common and had relatively low out-of-pocket costs

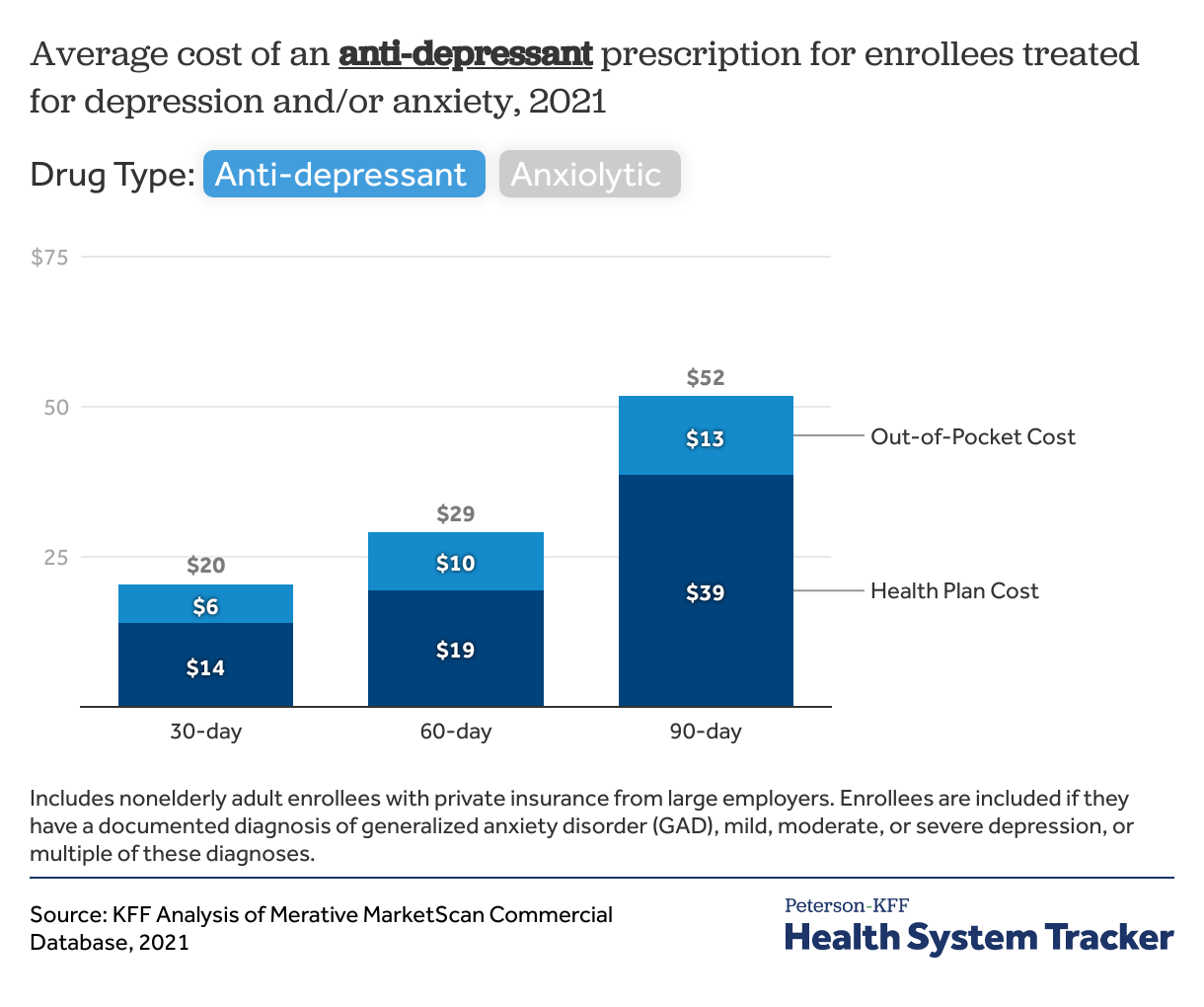

Among enrollees who were treated for depression and/or anxiety in 2021, 74% had at least one prescription for an antidepressant or anxiolytic medication. Antidepressants were more common (71% of enrollees) than anxiolytics (21% of enrollees). The likelihood of having a psychiatric medication prescription increased with the severity of depression. Eighty-four percent of enrollees treated for severe depression had an antidepressant prescription, versus 73% with mild depression. These medications had relatively low out-of-pocket costs for enrollees, averaging $6 for a one-month supply of an antidepressant or anti-anxiety medication.

Discussion

We find that enrollees with depression and/or anxiety spend almost twice as much out-of-pocket on their annual health services overall, compared to those without a mental health diagnosis. Further, enrollees pay for a larger share of mental health services out-of-pocket compared to other health care services. However, for enrollees with depression and/or anxiety, most of their out-of-pocket spending is for non-mental health services (70%). The relationship between mental health and health spending may be multi-directional. On one hand, those with mental health conditions require more care, and thus spend more. On the other hand, chronic health conditions and high health spending at baseline may lead people to develop secondary depression and/or anxiety. There is a high rate of co-occurrence between mental health conditions and other chronic physical conditions.

Even with private insurance, many adults with mental health conditions do not receive needed care – among adults with employer insurance and moderate to severe symptoms of depression and/or anxiety, 37% did not receive treatment. High costs can often lead people to delay or forgo needed health services. For example, despite mental health parity regulations, network adequacy issues persist, leaving many people to seek care outside of their insurance networks. Having to go out of network can substantially increase costs for individuals (and these costs are not captured in this analysis). In 2022, employers reported that their networks for mental health care were narrower than their overall provider networks, and only 44% believed their network of providers could meet their employees’ needs. Few large employers have added virtual or in-person mental health providers to their networks. This may reflect the ongoing provider shortage, with a high percentage of unmet need for mental health providers nationally.

These findings of higher health spending among privately insured individuals receiving treatment for depression and/or anxiety come at a time of rising health costs. Health insurance is already expensive for enrollees with private insurance, and treatment for mental health conditions can further escalate these costs.

Methods

This analysis is based on 2021 claims from the Merative MarketScan Commercial Database, which contains claims information provided by a sample of large employer plans. In 2021, there were claims for over 13 million of the 85 million people in the large group market. To make MarketScan data representative of large group plans, weights were applied to match counts in the Current Population Survey for enrollees at firms of a thousand or more workers by sex, age and state. Adults less than 65 years old with continuous enrollment in their plan for at least six months were included.

Enrollees were included if their annual spending was between $0 and the 99.5th percentile of annual spending. Total spending is the sum of the amount paid by the insurer and the amount paid by the enrollee. Out-of-pocket expenses are a sum of coinsurance, copays, and deductibles where applicable. The MarketScan database includes only claims covered by the enrollees’ plan and does not include services for which enrollees paid directly without the health plan being billed, claims denied by the health plan, any balance billing directly from providers to enrollees.

Enrollees with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) or mild, moderate, or severe depression were identified if they had at least one inpatient or outpatient claim with a target primary diagnosis. Depression with psychotic features and depression in remission were excluded. Enrollees were categorized as mild, moderate or severe depression based on their most severe inpatient or outpatient claim during the year. GAD is not categorized by severity level in ICD-10 diagnosis codes, so we are unable to look at differences between mild, moderate, and severe anxiety in this analysis. Enrollees with the target diagnoses were compared against enrollees with no treatment for any mental health diagnosis during the year. Therefore, enrollees with mental health diagnoses other than depression or anxiety do not appear in this analysis.

Specific services were identified using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, and office visits were classified as psychiatry versus other using standard provider and revenue codes. For services such as office visits, which can be for mental health or non-mental health diagnoses, services were classified as mental health if the primary diagnosis on the outpatient claim was for a mental health ICD-10 diagnosis code. Telemedicine claims were identified using CPT modifier codes and place of service codes. Add-on CPT codes for prolonged services that may be applied to outpatient office visits and therapy were not included because linking the add-on code to a specific service is inexact in claims data. Sensitivity analysis including and excluding add-on codes for outpatient services found negligible differences in average annual costs and utilization.

This analysis is limited in several ways. First, we only capture services that are billed to enrollees’ insurance plans, so any payments directly from enrollees to providers are not included, including self-pay psychiatry or psychotherapy services. We also do not include denied claims or balance billing directly from providers to enrollees. Given that in-network mental health services can be difficult to access, we are likely undercounting the true utilization rate and cost of psychiatric services in this population. Second, drug costs do not include rebates paid from pharmaceutical companies to insurers, so actual payments for psychiatric medications may be lower than reported in this analysis. While we show that enrollees with depression and/or anxiety have higher health spending than enrollees without a mental health diagnosis, we are unable to say whether mental health treatment is driving increased annual spending, or whether increased annual spending (and worse underlying chronic health) is causing higher rates of depression and anxiety.