As the coronavirus spreads rapidly across the United States, private health insurers and government health programs could potentially face higher health care costs. However, the extent to which costs grow, and how the burden is distributed across payers, programs, individuals, and geography are still very much unknown. This brief lays out a framework for understanding changes in health costs arising from the coronavirus pandemic, including the factors driving health costs upward and downward. We also highlight some special considerations for private insurers, Medicare, and Medicaid programs.

Coronavirus testing and treatment costs

The most direct impact the coronavirus pandemic will have on U.S. health care spending is through testing and treatment of COVID-19, but the extent of upward pressure on health costs depends on a number of still unknown factors.

One of the most important and yet still unknown factors driving health care costs is the number and severity of COVID-19 cases in the U.S. Projections vary, and are largely dependent on the success of public health efforts to contain or mitigate the spread of the virus. The University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) model suggests the outbreak is reaching its peak in the U.S., but others have warned of the possibility of another spike in cases if social distancing measures are relaxed too soon this summer, or possibly another outbreak this fall or winter. Particularly for private insurers and Medicaid programs, the geographic distribution of infections across states will also have important consequences for premiums and state budgets, discussed in more detail below.

Currently treatment is supportive, not curative. Some COVID-19 patients are enrolled in clinical trials to test the effectiveness of certain antiviral drugs, and human trials have begun to test the effectiveness of vaccines. If an effective treatment is identified soon, this could significantly reduce the strain of coronavirus on the health system, but the costs of any new drug treatments could add new costs to the system, affecting both public programs and private payers. Vaccines are not expected to be available for at least a year. While vaccines will prevent future cases and thus future spending, the vaccine will come at a cost as well.

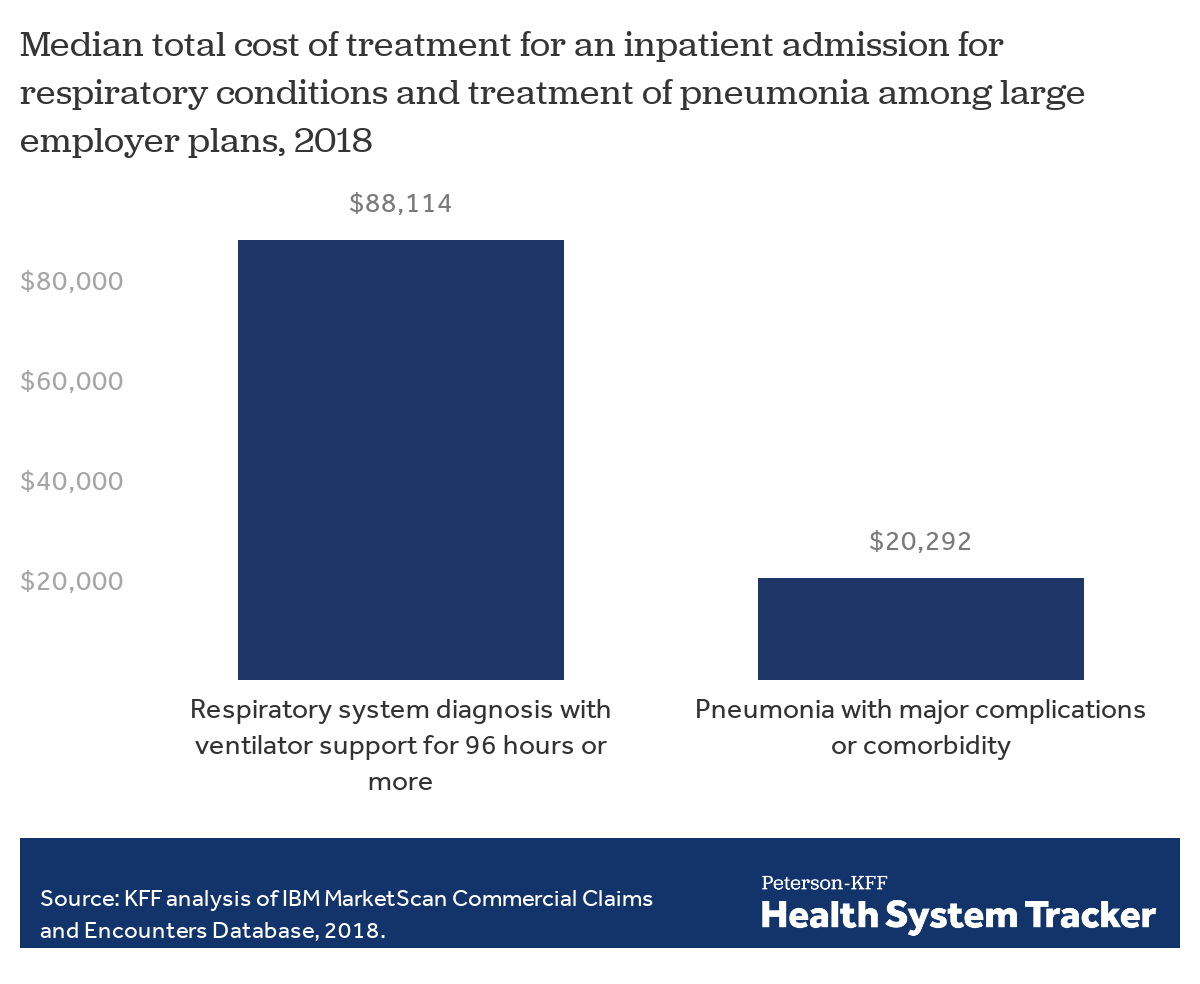

Roughly 15% of people infected by the coronavirus could require hospitalization, and a small share require invasive mechanical ventilation. The cost of these admissions will vary by severity and payer. In an earlier analysis, we estimate that, among people insured through a large employer’s private health plan, hospitalization for pneumonia ranged from an average of $9,763 to $20,292 in 2018 depending on severity and comorbidities associated with the condition. However, patients who need to be put on a ventilator would have much higher costs. In 2018, ventilation treatment for respiratory conditions ranged from $34,223 to $88,114 depending on the length of time ventilation is required, for patients in large employer plans. Treatment costs on a per patient basis for comparable admissions will be lower in Medicare and Medicaid, where providers are reimbursed at lower rates. For example, average hospital payments for pneumonia with major comorbidities or complications are $10,010 under Medicare, and hospitalizations for respiratory system infections requiring ventilator support are $40,218. Under the CARES Act, Medicare will pay a 20% premium for COVID-19 treatment, but per admission payment is still less than that for the same type of admission for people with private plans, on average.

Many hospitalizations for COVID-19 treatment will cost around $20,000 but treatment of the most severe cases would cost much more

Testing will likely involve relatively low costs on a per-test basis. Medicare, for example, pays $36 to $51 for each test. As testing becomes more widespread, though, the total cost will add up significantly. Hospitals and labs are now required to post the cost of coronavirus tests, and insurers, Medicare, and Medicaid are required to cover the tests without cost-sharing to the patient.

Covered California published the first national estimates of COVID-19 treatment and testing costs, ranging from $34 to $251 billion for commercial insurers (not including people enrolled in Medicare Advantage or Medicaid Managed Care Plans). America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) in consultation with Wakely, recently produced baseline estimates (assuming a 20% infection rate) of $84 to $139 billion in 2020 and $28 to $46 billion in 2021 for the direct cost of coronavirus testing and treatment of COVID-19, by private insurers (including commercial insurers, Medicaid MCOs and Medicare Advantage plans). However, using different assumptions of infection rates would yield widely different costs, ranging from a total of $56 to $556 billion over the two-year time period. The AHIP estimates do not include spending on Medicare beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. In a FAIR Health analysis of private, Medicare and Medicaid claims, estimates of total COVID-19 treatment costs ranged from $139 billion to $558 billion. The range of these estimates is indicative of the uncertainty around how many people will become infected and how many will need hospitalization.

Delayed or foregone care may offset some costs, but also cause pent-up demand

An indirect effect of the coronavirus outbreak is the additional strain on limited hospital resources, which will lead to some care being delayed or forgone. Additionally, due to both social distancing measures and the economic downturn, individuals may also forgo outpatient care or prescription drugs they would have otherwise used. Forgone care could offset some of the additional costs of treating people with COVID-19, though the degree costs are offset is still a question.

The IHME model suggests the number of people needing hospitalization could exceed the number of available hospital beds for some time to come in parts of the country. Hospitals in the U.S. are canceling or delaying some elective procedures to leave more beds, equipment, and staffing available for treating patients with COVID-19.

Elective care generally refers to any care that is not urgent, but many so-called elective procedures are nonetheless lifesaving or can significantly improve quality of life. Hospitals in the U.S. appear to be making different decisions about whether and which care to delay, making it difficult to model the cost effects. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), have release broad guidelines recommending procedures to be delayed. Additionally, some other types of hospitalizations may be avoided or delayed beyond just surgical procedures.

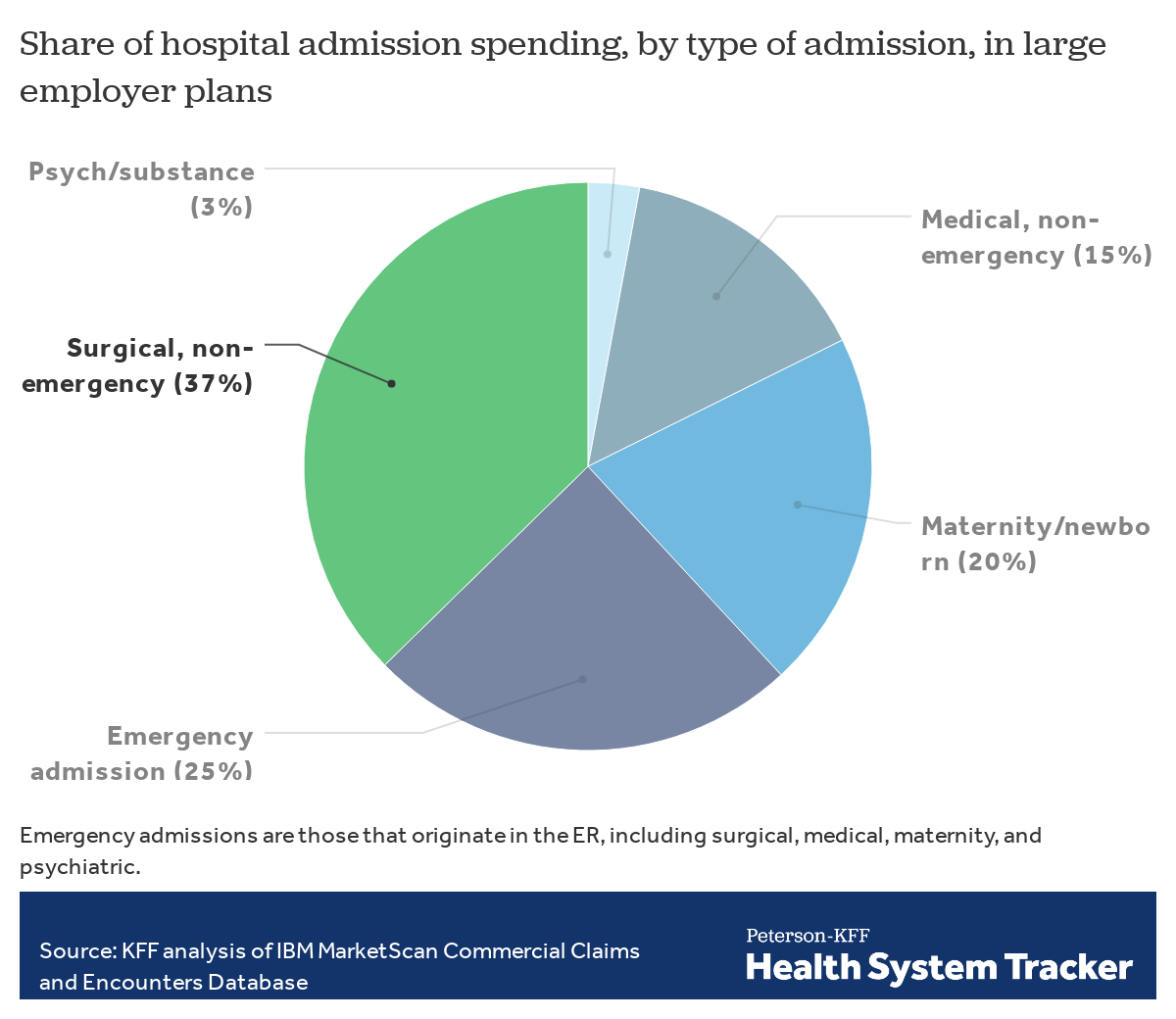

To understand the potential impact of delayed and forgone care and considerations insurers face in setting premiums for next year, we analyzed claims data from non-elderly enrollees of large employer plans using a sample of the IBM MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database. In 2018, 37% of hospital admission spending by large employer plans was on surgical procedures that did not originate in the emergency room, some of which may be delayed or forgone. Some of the surgical admissions that do not originate in the emergency room are nonetheless time-sensitive and life-saving. As hospitals across the U.S. are making differing decisions about which procedures to go forward with, often on a case-by-case basis, it is not yet possible to say how much of this or other hospital spending will be canceled or deferred into next year, but it gives a sense of the uncertainty and assumptions insurers may make in setting premiums for next year.

Elective procedures represent a substantial share of spending on hospitals

Although most forgone care is likely to put downward pressure on health costs this year, at least for several months, the delayed procedures and costs could shift to the next calendar year, raising spending for 2021. There is additionally some concern that certain types of delayed care could worsen health outcomes and cause higher spending later. For example, delaying or forgoing chronic disease management, either because of reduced access to medical providers or pharmacy services, could lead to more complications later.

Special considerations for private insurance and enrollees

Private insurers face particular challenges in predicting their costs, as there are still many unknowns around policymaking relating to cost-sharing requirements and risk mitigation programs. As the AHIP estimates demonstrate, the range of possible costs could vary ten-fold depending on the severity of the outbreak, not to mention additional unknowns such as the number and types of elective procedure delays, amount of pent-up demand, and uncertainty over policy changes.

Commercial insurers must submit premiums for 2021 to state regulators for review and approval in the next two months. In their premium calculations, insurers are not allowed to justify future premium increases based on any losses they expect this year. Instead, premium justifications must be based on assumptions about claims costs for next calendar year. If claims costs are exceptionally high this year, though, insurers might need to replenish surplus in order to remain solvent. Once finalized, in late summer, premiums will be locked in and insurers will be unable to change those rates for the duration of the coming calendar year.

The consequences of guessing wrong could be dire for some insurers. Insurers may have an incentive to over-price their plans, particularly on the individual market where many enrollees are subsidized and sheltered from premium increases. State regulators could encourage insurers to make similar assumptions about COVID-19 costs and pent-up demand so that premiums are not radically different from each other simply based on differing assumptions. However, the uncertainty around premium setting could also lead some insurers to decide not to offer coverage next year. In past years, when there was uncertainty around premium setting, some parts of the country were at risk of having no insurer offering exchange coverage.

Congress has not passed a risk mitigation program for private insurers in light of COVID-19. However, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) included two temporary market stabilization programs in its early years that could serve as models. Reinsurance would protect insurers against losses from extremely high-cost enrollees and a risk corridors program would protect against extreme gains or losses from inaccurate premium setting.

Reinsurance works by reimbursing insurers for a portion of claims cost for each enrollee that exceeds a certain threshold. If an enrollee’s costs exceed a certain threshold, called an attachment point, the plan is eligible for payment up to the reinsurance cap. Under the ACA, attachment points were set at $45,000 in the initial years of the program. As the program is intended to reimburse for extremely high cost individuals, and many COVID-19 patients will have hospitalizations that cost in the $20,000 range, reinsurance as designed under the ACA would have missed many of these enrollees and would likely only reimburse for those COVID-19 patients requiring intensive care or ventilation. The program could be altered to include condition-based reimbursement, but it would not address mispricing due to incorrect assumptions about non-COVID care like elective procedures being delayed or forgone.

A risk corridors program would more directly address concerns of mispricing, including inaccurate assumptions about delayed elective procedures and pent-up demand beyond COVID-19 treatment, by limiting losses and gains beyond an allowable range. The federal government would share in the gains and losses of private insurers that set premiums too high or too low. Under the ACA’s risk corridors program, insurers whose claims costs were lower than expected by more than 3% paid into the program, and those whose claims costs were higher than expected by more than 3% received funds from the program. If an insurer’s claims fell within plus or minus three percent of their target amount, the plan made no payments into the risk corridor program and received no payments from it. In other words, insurers would still experience some gains and losses, but both would be limited.

For private insurance enrollees, out-of-pocket costs remain a concern. Some insurers have voluntarily waived cost-sharing for COVID-19 treatment, and a mandate has been proposed though not passed at the federal level. For those whose costs are not waived, we have estimated that out-of-pocket costs for a COVID-19 hospitalization could exceed $1,300 for people who are insured by a large employer. Out-of-pocket costs would likely be higher for people covered by small businesses and individual market plans, as those plans tend to have higher deductibles.

Special considerations for Medicare program and enrollees

Older adults are at particularly high risk for COVID-19 complications and death, and virtually all adults ages 65 and older are covered by the Medicare program. While it is possible that Medicare spending will increase above projected baseline spending for 2020, the magnitude of that increase, and the longer-term impact, is not clear. Increases in Medicare spending would have spillover effects for Medicare beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket spending in future years, in the form of higher premiums, deductibles and other cost-sharing requirements.

The pandemic is likely to put upward pressure on Medicare spending due to the following factors: the number of Medicare-covered COVID-19 hospitalizations; how much Medicare pays to treat COVID-19 patients, taking into account the share of hospitalized patients requiring ventilator support, and the 20 percent increase in Medicare payments for COVID-19 patients; the share of COVID-19 patients requiring post-acute SNF or home health care, and the intensity of services they receive; the cost of medications used to manage patients outside the hospital setting; the cost of a vaccine, when it becomes available; and the number of beneficiaries who are tested for the coronavirus.

However, just like in private insurance and Medicaid coverage, increases in Medicare spending may be partially offset by delayed or forgone procedures and office visits. A reduction in spending due to postponement of such procedures would offset the increase in Medicare spending for COVID-19 patients, at least in the short term. It is not yet known what share of these procedures will be rescheduled for later this year or shifted into 2021, or whether the delay in care will lead to costly adverse health events down the road.

It is also not known the degree to which expanded telehealth services will impact Medicare spending. Prior to the outbreak, Medicare payments for telehealth were extremely limited under the traditional Medicare program. Based on new waiver authority included in the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act (and as amended by the CARES Act) the HHS Secretary has waived certain restrictions on Medicare coverage of telehealth services for traditional Medicare beneficiaries during the coronavirus public health emergency. This change could offset a decline in the number of in-person office visits and the associated Medicare spending that would otherwise occur.

Capitated payments by the federal government to Medicare Advantage plans, which currently provide coverage to more than one third of the total Medicare population, may not be materially affected by the coronavirus in 2020 (though the underlying costs to those plans certainly could). Beginning in 2021, Medicare payments to Medicare Advantage plans could rise faster than expected based on the experience of plans this year and expectations for expenditures next year, or if benchmarks rise due to higher traditional Medicare spending; if average spending for traditional Medicare beneficiaries rises due to COVID-19, then payments would be likely to rise for Medicare Advantage plans, as well, with considerably variation across counties, across the country.

For Medicare beneficiaries, the impact of COVID-19 on out-of-pocket spending in the short term will depend on whether they are infected and whether they require hospitalization for treatment. Although beneficiaries will face no out-of-pocket costs for testing or testing-related services, many would face exposure to costs for treatment, unless they have supplemental coverage that will pay some or all of these costs, or are enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan that is waiving cost sharing for treatment. For patients who do not have COVID-19, they may face a drop in spending if they delay health care services they might otherwise have received, such as elective procedures or office visits. Over the longer term, beneficiaries could face an increase in out-of-pocket costs for Medicare premiums and deductibles if Medicare spending for 2020 increases due to COVID-19 (beyond what it otherwise would have).

Special considerations for Medicaid programs and enrollees

Medicaid program costs are expected to increase as a result of dealing with COVID-19 because of the cost of treating currently enrolled patients with COVID-19 and because overall enrollment is expected to rise as unemployment increases and people lose their job-based coverage.

As a countercyclical program, Medicaid enrollment increases during economic downturns when people lose jobs and income and qualify for coverage. Increased demand and enrollment results in increased spending. As a condition to access a temporary increase in the Medicaid match rate, states must comply with maintenance of eligibility requirements and cannot restrict eligibility or make it more difficult to apply for Medicaid and states must also provide continuous eligibility through the emergency period. Increased enrollment and potentially higher costs tied testing and treatment of COVID-19 will put upward pressure on Medicaid costs.

Even aside from enrollment increases, COVID-19 could result in higher costs to Medicaid programs than anticipated, as in private insurance and Medicare. Most Medicaid enrollees are served through capitated managed care plans, so new unanticipated costs could be incurred by private insurers. States could have options to negotiate rate adjustments, provide additional “kick” payments for COVID-19 related costs, implement carve-outs of COVID-19 related care, establish risk corridors or make retroactive adjustments to address higher than anticipated costs. Recent CMS guidance speaks specifically about such adjustments for COVID-19 testing and for the telehealth services.

Similar to other payers, Medicaid programs may see some declines in utilization of non-urgent care; however, unlike other payers, a larger share of Medicaid spending may continue. The majority of Medicaid spending is for the low-income elderly and people with disabilities, which includes spending for long-term services and supports. These services provided in institutional or community based settings are ongoing and necessary to assist with activities of daily living and cannot be easily deferred.

Strategies typically employed to reduce costs in response to economic conditions may not be viable. In past recessions, states have tried to manage costs by freezing or cutting provider rates or implementing targeted benefit restrictions. However, as many providers are strained by the coronavirus response, provider rate cuts may not be feasible and targeted benefit cuts are unlikely to amount to significant reductions in spending (especially because spending on some optional services, like dental care, are generally small and may be naturally lower if individuals are not accessing those services due to the pandemic).

Medicaid may also be used as a vehicle to support providers as a result of COVID-19. An array of options may be available to help provide funding quickly to providers through Medicaid. For example, states can make advance, interim payments to providers based on historic claims. States can also pay higher rates for home and community based services during the emergency.

Discussion

The costs of coronavirus testing and COVID-19 treatment are expected to be high, reaching tens if not hundreds of billions of dollars, but there is extreme variation in estimates due to remaining uncertainty about the extent of the outbreak. Additionally, other care, such as for elective procedures and some outpatient care or pharmacy use, is likely to be forgone as hospitals take measures to free up capacity for COVID-19 patients and individuals put off care due to less access under social distancing orders or concerns over contracting the virus. On net, health spending could be higher this year and next than otherwise expected before the pandemic hit, but it is yet to be seen how upward and downward cost pressures will balance out.

Private insurer earnings calls and quarterly cost data will provide some clues into how net spending has changed, but insurers will soon need to make decisions about participation and premiums for 2021 with very limited information. The implications of inaccurate assumptions could include higher premiums, steep increases in future years, and insurers exiting the market.

Federal Medicare spending could increase more than it otherwise would due to COVID-19, but the magnitude of that increase is an open question. As is the case with private insurance, the increase in spending for COVID-19 hospitalizations over a period of several months in 2020 will be partially offset by the decrease in spending for non-urgent surgeries, procedures and other medical services. COVID-19 could lead to an increase in payments to Medicare Advantage plans in 2021, depending on the experience of plans in 2020, and whether higher spending on COVID-19 treatment is offset by reduced spending on non-urgent procedures. An increase in Medicare spending would have spillover effects for beneficiaries’ premiums, deductibles and cost-sharing, and come at a time when Medicare already faces long-term financing challenges.

Medicaid programs will experience increased spending from both the treatment of COVID-19 and increased enrollment as unemployment increases and people lose their job-based coverage. Some of the cost-cutting mechanisms Medicaid programs employed under past recessions may not be an option in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic.

Methods

We analyzed a sample of medical claims obtained from the 2018 IBM Health Analytics MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database, which contains claims information provided by large employer plans. We only included claims for people under the age of 65, as people over the age of 65 are typically on Medicare. This analysis used claims for almost 18 million people representing about 22% of the 82 million people in the large group market in 2018. Weights were applied to match counts in the Current Population Survey for enrollees at firms of a thousand or more workers by sex, age and state. Weights were trimmed at eight times the interquartile range.

Admissions were classified as pneumonia when the associated diagnosis-related group (DRG) was 193, “Simple Pneumonia and Pleurisy with major complications,” 194 with “complication or comorbidity” or 195 “without complication.” Admissions were classified as a respiratory system diagnosis with ventilator support required for 96 hours or more when the associated DRG was 207, and a respiratory system diagnosis with ventilator support required for less than 96 hours when the associated DRG was 208. Total cost was trimmed for admissions below the 1st percentile and above the 99.5th percentile within DRG.

We defined the type of admissions based on the classifications provided in the Marketscan database, similar to the approach used here, which classifies admissions into five categories: surgical; medical; childbirth and newborn; psychological and substance abuse; and, other. We defined an emergency admission as an admission that included at least one claim in the emergency room (as defined by “stdplac”).

The authors would like to thank Dustin Cotliar, MD, MPH for his contributions.

The Peterson Center on Healthcare and KFF are partnering to monitor how well the U.S. healthcare system is performing in terms of quality and cost.